They must really love their big airport in the Windy City.

What started as a one off (I thought) look at Winston Churchill’s Skymaster in January 2020 has already grown into a four-part exploration of that remarkable C-54 and its RAF sisters. That Skymaster story led us, naturally, to Orchard Place, IL where the US Government built a massive wood-framed factory and airport to enable Douglas to mass produce C-54s for the war effort.

The connection drew out more stories, including a contemporary description of the Douglas factory from the November 1943 issue of Flying and a set of gorgeous illustrations of ‘O’Hare City’ by local artist Phil Thompson (Orchard Place is now Chicago’s mighty O’Hare International Airport, with a distant echo of that proud heritage in its KORD designator.)

And yet, to paraphrase the opening to one of those articles, the story of the C-54 still isn’t finished with me!

Douglas poster

Some time back Chicago resident Joe Hanania reached out to airscape regarding an ‘interesting’ poster from the Douglas factory, that had hung on his office wall for years. Obviously I was intrigued; Joe sent a picture; and I was definitely not disappointed.

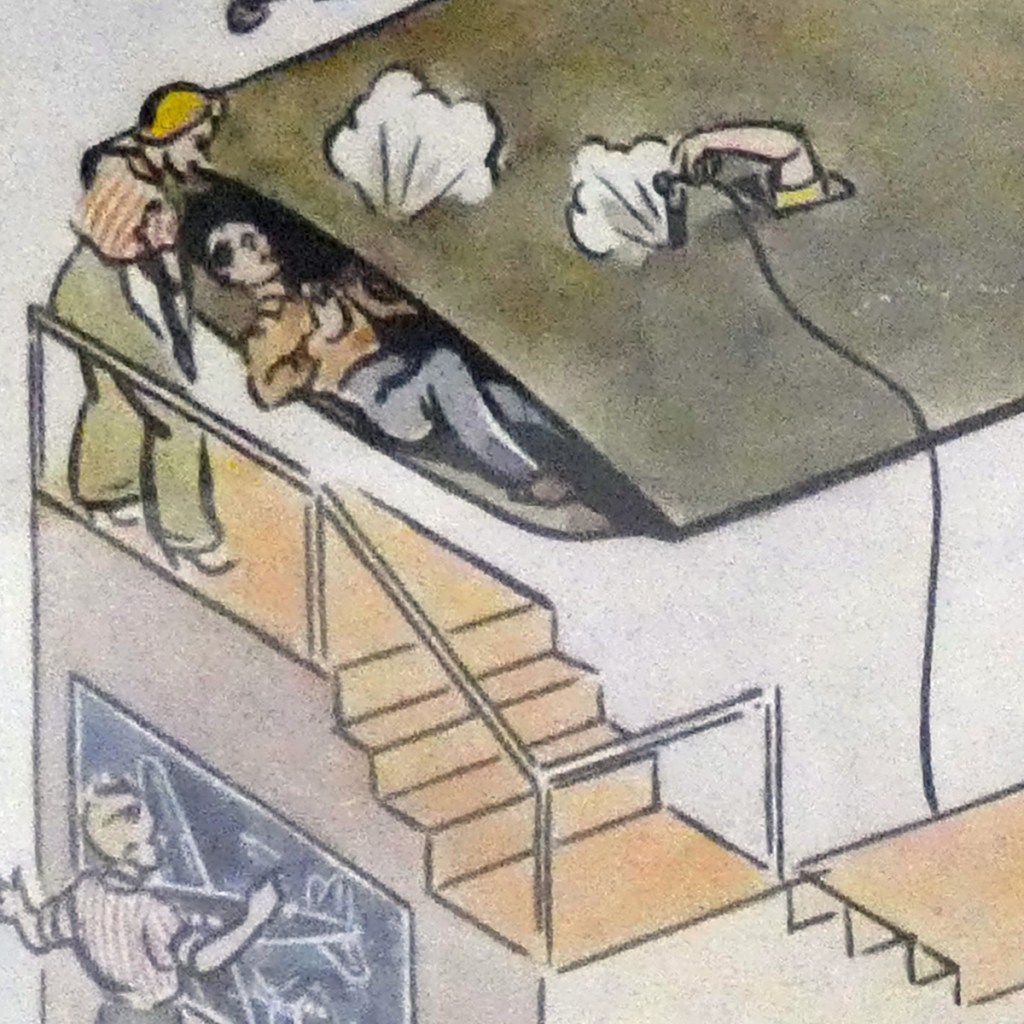

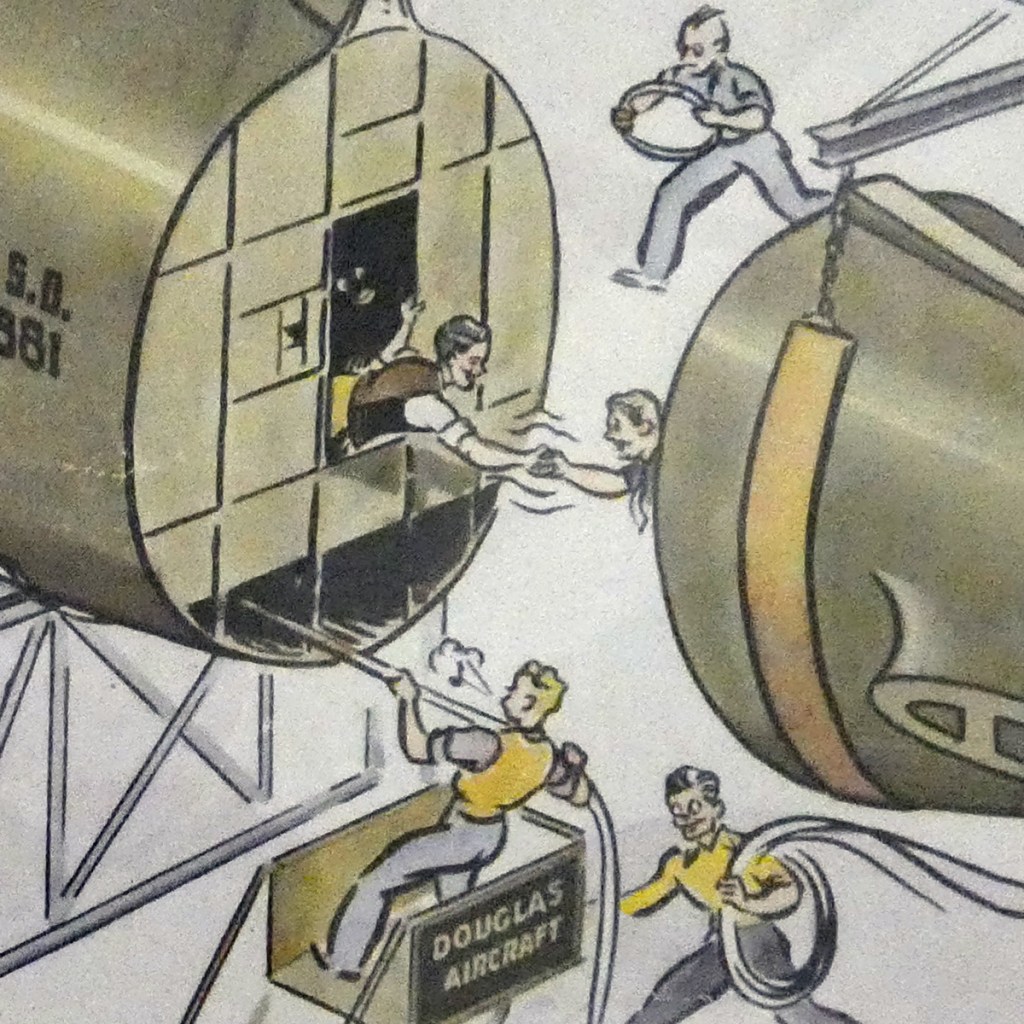

Signed by Production Illustrator Gene Ellis (a person and role I would love to find out more about), the poster shows a cartoon swarm of Douglas workers assembling a C-54 on the Orchard Place line, while caricatures of Hitler, Tojo and Mussolini look on in alarm.

The detail in the image can best be summed up as controlled chaos. Riveters work in locations and positions that would challenge a sleeping cat. At top centre, a steady stream of cartons are carried in from a parked transport plane. A wing panel and an engine unit are being rushed in from top left, a tail cone from bottom left, while further wing sections and fuselages are being prepared to the right.

I’ll leave you to soak it all in for a minute… (Make sure you click to view the large version.)

Something more going on

At first glance, all this industrious rush appears to be just a fun look at regular wartime urgency. But there are a few clues that something more is going on.

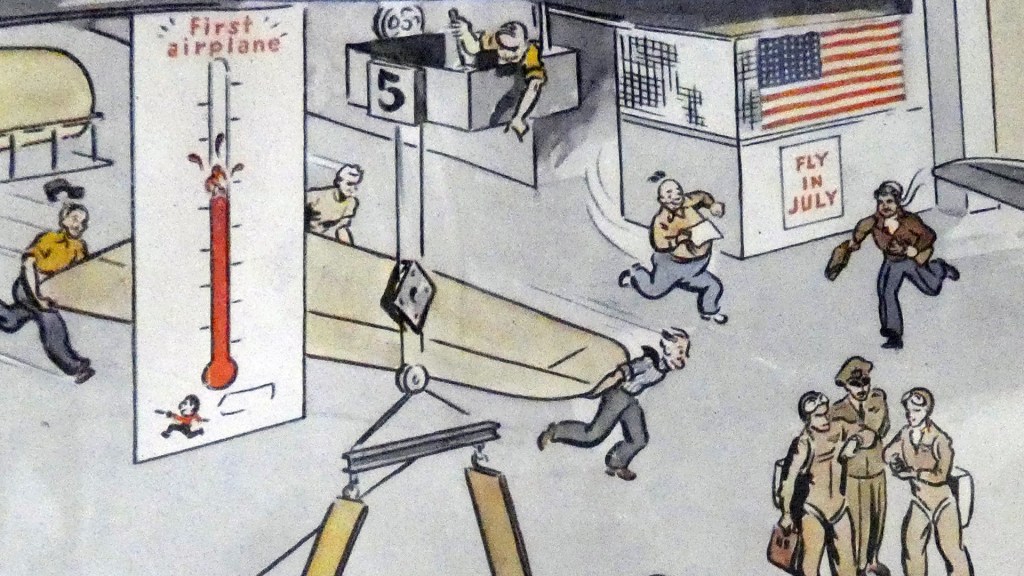

Under the US flag at the top, and again by the waiting fuselages, are banners saying ‘Fly In July’. (In a delightful detail, the only people in the poster who are not rushing around are the plant doctor and nurse, next to that main banner.)

Then there’s the thermometer at top left with the legend ‘First airplane’, the waiting aircrew, the boxes marked C-54A. And, just visible along the lower left margin, are the words Souvenir of ‘Fly in July’ Production drive, Chicago Plant, July 1943.

On the main fuselage, just aft of the cockpit section joint, is the title ‘Ship No. 1’. It’s hardly nose art, but it points to the full story.

The massive plant at Orchard Place was not just a commercial venture for Douglas. It was essential to the War Department’s plans and the Army Air Forces’ need for as many long-legged load-hauling C-54s as possible. One C-54 could carry twice as much as a Curtis C-46 Commando, and five times the load of the ubiquitous Douglas C-47.

The giant wooden factory was planned and build under the supervision of Army engineers. As soon as a section was finished, Douglas would move in its machine tools, jig builders and workers, and start making parts.

In that regard, the factory was never ‘opened’ as such. It was largely operational by the time it was finished, and C-54 sub-assemblies were already being completed.

However, the Army Air Forces couldn’t increase their airlift capacity soon enough.

Fly in July

To meet their demands, Plant Manager John D Weaver created the Fly in July drive at the new plant.

“We must deliver our first plane on time,” he wrote in a special staff bulletin in mid-April.

“I have given both your promise and mine that we will do everything in our power to deliver our first plane ahead of schedule. This means both you and I must work as we never have before. It means that, starting today, the greatest production drive in the history of this company is under way… We must produce!”

As shown in the souvenir poster, huge three by six foot (1 x 2 metre) Fly in July banners were placed along the assembly line and posters were also put up throughout the rest of the factory. Huge cartoon clocks showing the number of days left until the end of July were also set up over each main production jig and a 15-foot (4.6 metre) thermometer really was erected at the head of the assembly line, showing the various stages to completion of the completed plane.

On a smaller scale, wooden banner stands accompanied components destined for the first airframe as they moved through the factory, so staff could identify them and treat them with appropriate urgency.

Staff also wore special badges on their lapels and every factory memo or piece of correspondence bore a Fly in July sticker.

Factory fresh

That remarkable effort brought remarkable results.

Not only did Chicago’s Douglas workers produce a complete C-54 by the end of July, they actually rolled it out into the summer sunshine a week early!

True to John Weaver’s promise, that first aircraft – USAAF serial 42-72165 – took to the air on 30 July 1943. The staff were treated to a well-earned break and, putting the factory in true scale, 50,000 were on hand to witness the official dedication of the plant and the first flight of their first Skymaster.

A pretty brunette riveter named Jennie Giangreco was named “Miss C-54” and given the honour of starting the engines. Next, Douglas test pilot Win Sargent took off and flew the big bird around the airfield for about 25 glorious minutes while her builders clapped and cheered below.

And then they all went back to work. There was still a war to be won.

Ship No.1

I can’t find exactly what happened to #42-72165 (msn 10270/DC1 – where, this time, DC stands for Douglas Chicago) after that initial flight.

It seems obvious that it joined the USAAF Air Transport Command but it was officially being operated by United Airlines when it was damaged in a taxiing incident at Hamilton Field, Marin County, CA on 13 September 1944. Hamilton was a major staging point for ATC operations across the Pacific at the time.

The aircraft next appears in September 1946, when it was returned to Douglas and converted to a DC-4 passenger configuration (conversion number 82). It was then twice registered in Venezuela for Lineas Aereas Venzolanas, but neither assignment was taken up and the airliner was registered in the US as N91078 instead.

Finally, it was sold to Northwest Orient Airlines in April 1947 and re-registered as N95425.^

On 23 June 1950, at around 01.15 in the morning, the aircraft disappeared from radar as it crossed Lake Michigan in severe storm conditions, during the New York LaGuardia to Minneapolis leg of a daily New York – Seattle service.

All 55 passengers and three crew were killed in the crash.

Lake Michigan is approximately 150 feet (46m) deep in the area where oil and light wreckage were later discovered, and there is a deep silt layer on the lake bottom.

As a result, the loss of Flight 2501 has never been conclusively resolved and the main wreckage has still not been found. All we know is that the aircraft’s service ended less than 65 miles (~100km) from where it began…

They don’t make ‘em like that any more

‘The Wooden Giant’ at Orchard Place used 30 million board feet (70,792 m3) of lumber in its construction, saving 30,000 tons of strategically valuable steel. Under arrays of floodlights, construction shifts continued around the clock. The complete project included storage and reticulation for a million gallons of water per day, wiring for 20 megawatts of electricity, a railway yard with its own 20-ton locomotive, and an airport with four 5,500-foot (1,676m) runways.

To save even more steel from reinforcing, each of the 150 feet (46m) wide runways was built on a stone base 15 inches (381mm) thick, covered by a slab of concrete between seven and ten inches (178 to 254mm) thick.

The 1,460 acre (591ha) greenfield site had only been acquired by the War Production Board in the first half of 1942 and clearing of trees and fences began in July that year. Work on the two million square feet (185,806sq.m) main factory building began in August. Material deliveries for making C-54s started in March 1943.

It is absolutely incredible that the plant launched the first of 655 complex four-engined transports just four months later and just over a year after the first sod had been turned.

We can never forget the factory hands – including 19 million women – who mobilised US industry in the early 1940s. But we should also pay tribute to those construction crews that made it all possible.

I have said it before – and I’ll repeat it now: Even with its many feats of arms during World War Two, the home front mobilisation that delivered ‘the arsenal of democracy’ really was America’s Finest Hour.

^Thanks as always to (Chicagoan) Joe Baugher for the aircraft data.

‘Fly in July’ details from Douglas Airview, May 1943

Love it!

What the mind of man can conceive the hand of man can create.