Click here for previous chapters

The next day special training in land planes began for us seaplane pilots. I felt completely out of my element.

What most surprised me when flying land planes was how little their pilots seemed to worry about the wind direction. When flying seaplanes one must take off and land directly into the wind. That’s the first rule a seaplane pilot learns. Even the slightest amount of crosswind is unacceptable.

Thus, the seaplane pilot is always asking, what’s the wind doing? And when flying he’s always observing the terrain and thinking of where and how to safely land if the engine quits. When flying over the ocean he must constantly observe the sea surface to determine the wind direction.

Which way the wind is blowing

To give an extreme example, if the pilot is foolish enough to land with a tailwind the plane will always capsize. If he lands with a crosswind the upwind wing can lift and the downwind wingtip can catch the water, causing an accident. Even after landing and taxiing to shore the pilot must constantly be aware of the wind and use the ailerons as needed.

Of course, strong winds also generate waves that push the plane around. And when there’s a big swell running the seaplane is practically at the mercy of the waves. Unlike land planes, seaplanes are almost never on stable ground.

In contrast, the pilots of land planes hardly seemed to care about the wind.

As I told one of my former classmates as we watched the Zeros taking off in a crosswind, “Look at those guys! They don’t even care which way the wind is blowing.”

It all seemed reckless to me, but at least they didn’t take off with a 100% tailwind.

Of course, as long as they were taking off from a runway, they couldn’t choose any direction they liked, so in that sense it was sort of like a catapult takeoff. All of which meant that they could usually take off just fine regardless of the wind direction.

Old, war-weary aircraft

Another area that caused me a lot of trouble was braking. Brakes were used constantly when taxiing to and from the runway, moving the plane somewhere and when parking.

All of this required the use of differential braking and a deft touch on the brake pedals. Pushing on the right brake pedal makes the plane pivot around on the right wheel and turn right.

The problem was, the Zeros at Kō-no-Iké were old, war-weary aircraft and had all sorts of idiosyncrasies, one of which was their poor braking action. When I applied the brakes and then released them one or both of the brakes usually wouldn’t release. These dragging brakes caused me no end of aggravation.

When the brakes wouldn‘t release I couldn’t get the plane to go where I wanted and it would just spin around in circles. In that case, if I stepped on the opposite brake pedal and gunned the engine to force the plane forward it tried tip over onto its nose and hit the prop on the ground.

Anyway, that was my introduction to the differences between seaplanes and land planes.

The brake pedals are connected to the rudder pedals and are mounted just above them. The pilot operates the brakes by pressing on them with the tips of his feet.

Releasing that pressure releases the brake, at least it’s supposed to…

Like a car stuck on train tracks

One day I pulled out onto the runway to prepare for takeoff but the brake on one wheel wouldn’t release and the Zero just spun around in circles like a dog chasing its tail. Worse, there was a bomber at the other end of the runway preparing for takeoff and, like a car stuck on the train tracks, I was blocking his way.

Fortunately, our training planes had tail numbers and we soon figured out which ones to avoid. The mechanics were also fed up with the planes that always needed fixing.

But the planes were used hard and they were worn out to begin with, so it wasn’t a surprise that they broke down constantly. When a plane was known to leak oil, for example, the pilots did everything they could to avoid flying it. Even when we were assigned a certain plane, if it had a bad reputation we found ways to avoid it.

Braking issues

It was due to my seaplane background that braking issues caused me so much trouble. This was because when taxiing a seaplane from place to place or when returning to port the engine is generally running at low rpm.

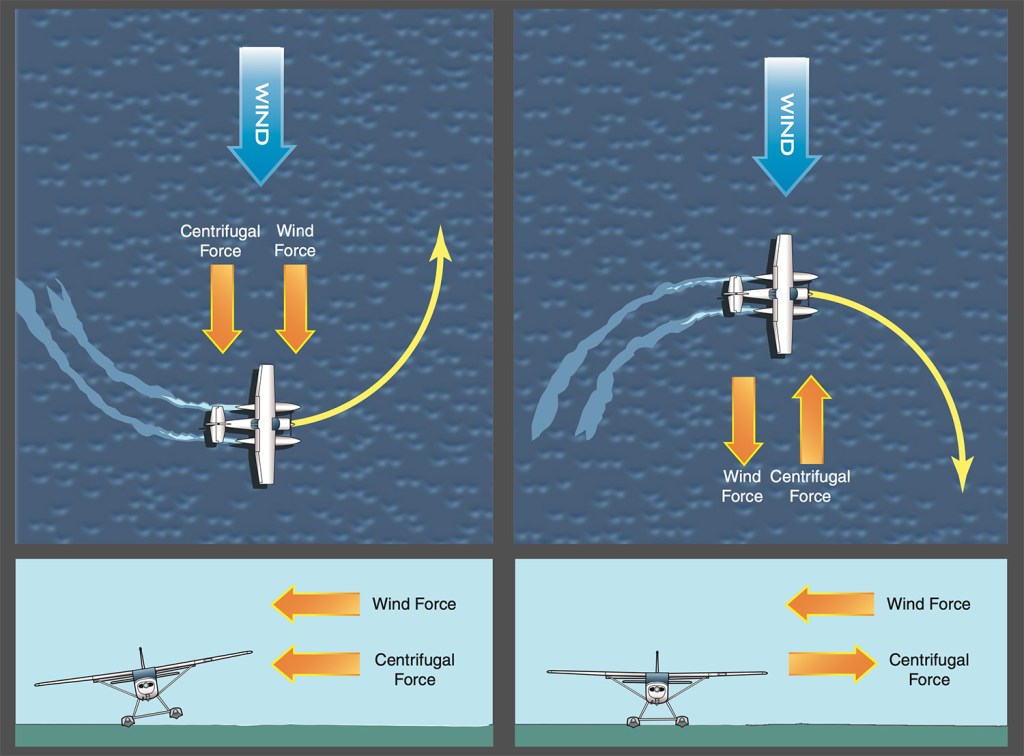

If the wind is strong and there’s a direct crosswind requiring takeoff power to taxi against it, a seaplane tends to turn into the wind because the seaplane’s floats act like boats.

For example, if the wind is blowing strongly from the right, in order to keep the plane from heading into the wind you have to use full left rudder, lots of power and right stick. Because this puts the left aileron down, the combination of the wind striking the down aileron and the fully deflected rudder will cause the plane to turn left.

However, because the wind can quickly change direction the pilot must adjust the aileron and rudder inputs accordingly. All this becomes worse when there’s a sudden squall. In short, seaplane pilots must keep a close eye on the wind. Only after a pilot can confidently taxi his seaplane in all wind conditions is he considered competent.

An inextricable relationship with the wind

Ocean swells are another challenge seaplane pilots have to deal with. Inland seas and lakes have smooth water, but since seaplane bases are often located along coastlines, ocean swells are always present. And when the wind and swell directions differ, operations become even more challenging.

Even if the pilot is taxiing into the wind correctly but the swell is coming in at 90 degrees the plane can be rolled so violently that a wingtip float can be ripped off if a wing digs into the water.

So, how did we deal with this?

Well, seaplanes with dual main floats didn’t have this problem, but the Type 95 recon seaplane and the Zero recon floatplane both had small wingtip floats. If one of those digs into the water it can spin the plane around and cause it to capsize.

The gist of all this is that seaplanes have an inextricable relationship with the wind. The expression ‘Flying is a constant struggle’ always struck me as very fitting.

Even today, whenever I’m able to look down upon the sea I instinctively note its condition and calculate the wind’s strength and direction. If there are streaks on the surface resembling those made by a sweeping broom it’s easy to tell that the wind is blowing. But determining the wind’s true direction is difficult, as a headwind can look like tailwind.

Flying the Zero!

Correctly determining the wind’s direction by observing the surface of the sea is called ‘reading the wind’. It’s a skill that every seaplane pilot must master. And that’s what I had a hard time dealing with at Kō-no-Iké. I couldn’t get over the fact that the pilots seemed oblivious to and even uninterested in what the wind was doing.

Eventually, though, I just gave up and stopped worrying about it. After all, they couldn’t build runways for every possible wind direction. So I just got on with fighting the sticking brakes on those old Zeros until I got used to land planes.

Whether the brakes were sticking on a particular plane or not I often found myself unintentionally applying them while pushing the rudder pedals when taxiing. This was, of course, never an issue on seaplanes. I just had trouble unlearning all my old habits.

However, there was one thing that brought me immense pleasure — flying the Zero!

Compared to the seaplane I was accustomed to it was so nimble and responsive that it was really fun to fly. Of course, I expected it to be so, but the ease with which it responded to my every control input made it a joy to fly. I was reminded of the axiom that ‘the initial trainers are the hardest to fly’.

For example, when turning the Zero you merely had to lift a wing slightly and off it would go. There was no need to use rudder. When flying a trainer or a larger heavy aircraft, though, you always had to use plenty of aileron and rudder, all this while your instructor yelled: ”Keep that ball centered!”

You could quickly get into trouble

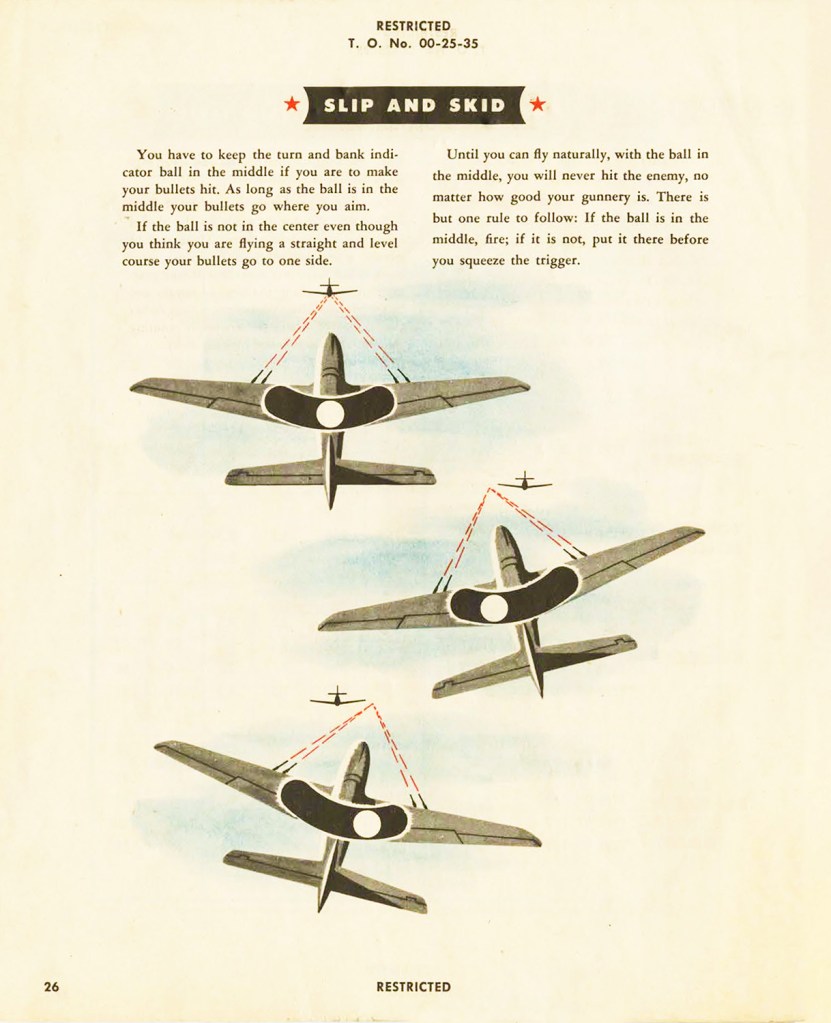

The ‘ball’ was the little black ball in the turn coordinator that indicates the correct amount of rudder to use when turning. Located at the center of the instrument panel, the turn coordinator functions like a carpenter’s level. When the aircraft is flying straight and level the ball remains centered.

When the plane turns the ball moves in the direction of the turn unless the pilot applies rudder in that direction to keep the ball centered. Its purpose is to keep the turn ‘coordinated’ meaning that the plane is neither ‘slipping’ nor ‘skidding’ in the turn.

On a civilian aircraft this instrument helps pilots fly smoothly and safely. In combat aircraft it can get a pilot killed or keep him alive.

When an aircraft slips or skids, the air hits the side of the aircraft and the nose of the aircraft is untrue to the relative airflow. This causes the aircraft to lose speed and altitude and it become more vulnerable to attack.

However, skidding or slipping also plane makes it more difficult to shoot down, because its path through the air is not in the direction its nose is pointed. Thus, even if the plane is centered in the pursuing fighter’s gunsight it will be difficult to hit. Likewise, if the pursuing aircraft is slipping or skidding while firing, the track of the bullets will also be skewed.

In any case, the Zero was easy to fly. You could skid or slip it with ease. But that didn’t mean it could be flown sloppily. The same qualities that made the Zero so responsive also meant that you could quickly get in trouble if you didn’t fly it accurately.

In that sense it was a very good aircraft in which to master basic flying skills.

NEXT TIME: Training like crazy to die >

These extracts are from the diary of Masa’aki Saeki, trainee Yokosuka MXY-7/K-1 Ohka pilot, 721st Kōkūtai Jinrai Butai, Imperial Japanese Navy.

Translated by Nicholas Voge and shared with permission.

Nicholas Voge is a retired Pt. 135 airline pilot who spent his younger years living in Japan where he worked as a translator, copywriter and riding model for the Japanese motorcycle manufacturers. His translations include The Miraculous Torpedo Squadron, The Inn of the Divine Wind and Kaiten Special Attack Group, A Story of Stolen Youth.

Last para needs a tidy-up.

Thanks Bob. Needless to say, I’ve had the elves flogged.