“I’m going to make this thing fly – do you hear me? Then I’m going to set it a-fire and never have another thing to do with airplanes.”

Clyde Vernon Cessna, 1911

If you’ve ever felt like you were struggling to nail something, spare a thought for Clyde Cessna: He learned to fly at the School of Hard Knocks, and his only instructor was the ground.

There seem to be a number of different stories circulating about how Cessna learned to fly. There’s no doubt that he taught himself, and the sources all agree that it took him over a dozen crashes – each of which meant he had to repair the aircraft himself – and apparently took him to the limits of his patience.

Even with qualified instruction, I think learning to fly probably tests everyone’s determination at least once along the road. So thank goodness bending a dozen or so planes is no longer part of the curriculum.

Clyde Vernon Cessna

December 5th, 1879 – November 20th, 1954

Some versions of the story have Cessna building that first airplane himself, from a drawing of a Bleriot XI that he found in Popular Mechanics magazine. I’ve been looking into the story for an article that will be appearing in The Flying Machine: Early Aero Quarterly, and the truth is likely a lot more pragmatic.

In fact, Clyde Cessna could possibly qualify as the most pragmatic of all dawn-of-flight aviators.

As a general rule aviation’s notable early businessmen, including Bleriot, Grahame-White, Curtiss and the Wright Brothers themselves, all began with a fascination for flying itself. Not Cessna. Aged 31, a successful small-town auto-dealer and mechanic, and a father of two, his motivation was all business.

True, the pure spectacle of powered flight might have brought him to Oklahoma City in early 1911, to see a demonstration by Alfred and (the late) John Moisant’s International Aviators. More likely it was his mechanical curiosity though: Cessna had been a gifted mechanic since he was a boy in Kansas. Repairing and improving farm machinery as a young man had bankrolled his car dealership in Enid, Oklahoma.

Flying a Bleriot XI

Either way, he became hooked on flight when – wait for it – he heard that the troupe was being paid $10,000 for their single appearance. One of the pilots in the show, flying a Bleriot XI, was the already-famous (and soon to be more so) Roland Garros, and he and Cessna got talking.

It’s not clear whether Garros let slip about the 10 Gs, but he certainly told the inquisitive Cessna that a copy of his little Bleriot could be purchased from the Queen Aeroplane Company of Fort George Park, on the corner of 197th Street and Amsterdam Ave, New York City.

Scraping together all the money he could, Clyde Cessna took the train north to New York. He then spent several weeks working in the Queen Aeroplane Factory – presumably he paid his deposit and then offered to ‘learn the airplane’ while he waited for it to be built – before shipping his new investment back to Enid.

The going rate for a new ‘Silver Queen’ was $1,750 in 1911, or $2,500 with a three cylinder Anzani motor (as used by Louis Bleriot for his 1909 Channel crossing).

Cessna would later claim he spent $5,000 on his airplane (see below) although quite how he arrived at this figure is unclear. If he ever took up Queen’s Anzani option, he certainly didn’t install the little 40HP motor on his plane. Instead, he ordered a powerful V8 engine from an unnamed source and had that shipped to Enid too.

However the V8 was delivered late and, even then, the gifted Cessna couldn’t get it to run properly. So he purchased a four-cylinder, Elbridge Aero-Special and installed that.

Jet, OK

True to his vision (of earning $10,000 per outing), Cessna registered the Cessna Exhibition Company and booked its first appearance before his new license-built Bleriot, which he named Silver Wings, had even arrived from New York. The delays with the V8 motor meant this had to be a static display only, but no-one seems to have minded. And besides, the ambitious new aviator still hadn’t learned to fly!

That became the next order of business and, in May 1911, he shipped the Silver Wings out to salt flats at Jet, OK, some 40 miles north of Enid. The exact details of that summer’s flying lessons aren’t well documented. We know they spawned the quote at the top of this article – and probably some more unprintable outbursts as well.

‘The Bird Man of Enid’

A figure of between 12 and 15 crashes seems about right, and the Silver Wings would be substantially rebuilt by Cessna as he repaired the damage from each ‘lesson’ and tried again. Ultimately, his persistence paid off and Cessna finally recorded a successful flight of several miles on December 17th, 1911.

The mocking of local witnesses quickly turned to adulation and Cessna was heralded as ‘the Bird-man of Enid’. Shortly afterward he gave his first paid flying exhibition – which ended in yet another crash after a mile-and-a-half – but Clyde Cessna was on his way.

He was known for his very fair arrangements. He’d take a large share of the gate, but only if he made a flight of five minutes or more. So that fateful first showing may have been a bust, but he made $200 from his second outing and things continued to improve.

Classic Cessna

In April 1912, Cessna wrote to the Elbridge Engine Company praising their Aero-Special and enclosing various newspaper clippings of his exhibition flights. He only mentions one significant accident from the previous year – a fall of 75 feet – and then says he built himself a new airplane over the winter.

This would appear to have been the original Silver Queen with all his repairs, modifications and improvements. Most notable of those was a new undercarriage arrangement. Gone was the classic Bleriot arrangement of sprung tubes forming a large square around the forward fuselage (see the photo of the Moisant Aviators’ Bleriot); replaced by a simple, agrarian steel leaf spring with the wheels attached to its ends. Classic Cessna.

All the repair work opened Cessna’s eyes to another business opportunity. By 1913 he’d built himself a new, even better airplane and, during a weekend of exhibition flying across the state line in Kansas, he mentioned to the civic leaders of Wichita that he’d like to establish an airplane factory there. The idea was well received, although nothing happened right away.

1914 saw Cessna in yet another new craft, this time powered by a 60HP, 6-cylinder Anzani radial engine and capable of 90mph. Another two summers of successful flights ensued.

Then, in August 1916, the businessmen of Wichita came good, offering Cessna space in an old railway car factory that belonged to J.J. Jones Motor Company if he would establish an airplane factory and flying school there.

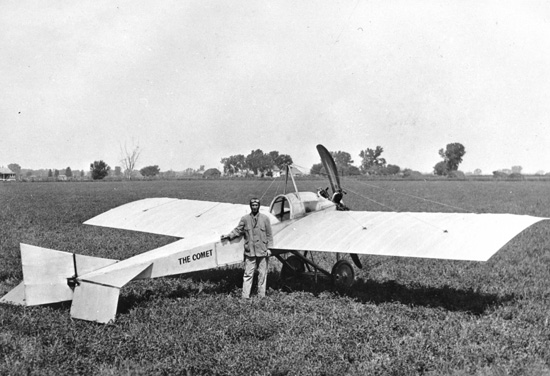

The Comet

It was just what Cessna had been waiting for, and by June 1917 he had built a new two-seat design around the 60HP Anzani, and enrolled his first five students at $400 each. When the two-seater made a 60 mile flight at an average speed of just over 124 mph it earned a name – The Comet.

Various sources claim Cessna built airplanes in 1911, 1912, 1913 and 1914, and he’s widely credited with building the first airplane in the midwest sometime during that period. However most of those new designs now appear to have been built in a continuum of repairs and improvements to the original Silver Wings with a series of different engines.

What is certain is that by 1916 Clyde Cessna had become a skilled aircraft constructor, and The Comet was indeed an original design that fully validated his long self-education.

A footnote in aviation history

As well as running the new enterprise, Cessna continued exhibition flying and farming his family’s land at Rago, Kansas about 30 miles west of Wichita. So, as the US was inexorably drawn into WW1 and civil flying suffered, Cessna decided to give up his aviation activities and fall back on growing wheat.

At this point, Clyde Cessna might have been little more than a footnote in aviation history if it wasn’t for an enterprising salesman from the E.M. Laird Company, named Walter Beech. He tried to sell Cessna new Laird Swallow in 1922 but the wheat farmer demurred. He and Beech liked each other though, so when Matty Laird went his own way in September 1923, Beech and the E.M. Laird Co’s designer, Lloyd Stearman, found a willing partner for their own aviation enterprise.

It’s still fascinating to imagine Cessna, Beech and Stearman sitting on the farmhouse porch at Rago, dreaming of what they might achieve. I bet they had no idea how much…

Together with a handful of investors from Wichita, the three trio formed Travel Air, Inc on February 25th, 1925. Clyde Cessna was appointed its President that May. The company built a factory on land in East Wichita. Later, it would be home to Beech Aircraft.

In October 1926 Lloyd Stearman decided to strike out on his own, while Beech and Cessna carried on with Travel Air. But Beech wanted to build biplanes and Cessna had always liked monoplanes. Tension increased as productivity stalled and so, when three Wichita businessmen offered to buy out Cessna’s shares in Travel Air a few months later, he sold.

On the map

He then used the money to establish the Cessna Aircraft Co in April 1927 and immediately set to work on the first of his characteristic high-wing cabin monoplanes. The first of the line was the Cessna Phantom – a three-place plane with a 36 foot wingspan, that delivered 100mph from its 90HP Anzani radial.

A brief partnership with motorcycle dealer Victor Roos followed, along with the design for a Wright Cyclone powered Cessna. However acquiring copies of the hugely popular Cyclone proved difficult at best and Cessna adopted a smaller Warner radial instead.

Using a modified, 110HP Warner, race pilot Earl Rowland flew a Cessna Model AW to outright victory in the 1928 New York to Los Angeles Air Derby.

The victory earned Cessna $11,000 in prize money and a flood of orders.

But more importantly, it put the Cessna Aircraft Co. on the map – and, with it, Clyde Cessna’s formula for relatively simple, aerodynamically efficient, high wing monoplanes.

The Cessna DC-6

Fate hadn’t quite finished testing Cessna though. HIs young company desperately needed a successful design to follow the AW and eventually earned certification for its new DC-6 four seater on October 29th, 1929 – the day Wall Street crashed and triggered the Great Depression.

The DC-6 was a smaller version of a six-seat design called the CW-6, and should have done well. But the Depression bit hard in the mid-West, and everywhere in civil aviation. Cessna Aircraft managed to build a creditable 44 copies of their new tourer – 20 as the DC-6A ‘Chief’ with a 300HP Wright R-975 Whirlwind and 24 as the DC-6B ‘Scout’ with a 225HP Wright R-760. In 1942, four of each would be impressed into US Army service as the UC77 (DC-6A) and UC-77A (DC-6B).

It wasn’t enough to save Cessna’s second aircraft enterprise though. By late 1931 the company had filed for bankruptcy protection and early in 1932 it closed its doors. Once again, Clyde Cessna went back to growing wheat for a living.

Never give up

He didn’t stay away for long. Along with the DC-6, Cessna had built a series of racing planes through the early 1930s, culminating in the CR-3, which he must have completed outside of the company as it first flew in June 1933.

Built for race pilot Johnny Livingstone who’d been beaten by the CR-2 the year before, the CR-3 won every race it entered until Livingstone was forced to bail out when the gear wouldn’t come down at the end of repositioning flight in August 1933.

The success of that final racer was enough to tempt Cessna back to Wichita. He was able to re-form the company in 1934 and sell it on to his nephews Dwane Wallace (a newly qualified aeronautical engineer) and his brother Dwight.

Aged 55 and living comfortably off his farm earnings, Clyde Cessna was happy to take an advisory role in this third iteration of an aircraft company bearing his name. And this time, the business flourished.

Working with his Uncle and some modern ideas, Dwane designed the Cessna C-34 Airmaster. First flown in June 1935, it would prove to be a good seller with solid development potential. Ultimately, it evolved into the C-165 and the cornerstone of the ultimate Cessna Aircraft Company.

Now, nearly 200,000 airplanes later, Clyde Vernon Cessna – the man who wanted to burn his first aircraft – has probably played a part in more aviation careers than any other individual, period. (Except maybe Sir Isaac Newton, but that’s another story…)

And his first lesson is: Never give up.

I enjoy all your posts mate – but this one I think was the best so far. Truly incredible story and a great read.

Andrew

________________________________

Thanks Andrew. I should add that I came to Cessna’s story because The South Australian Aviation Museum is restoring a replica of ‘Silver Wings’, built from aluminium tube by Ross Aviation in 1966. Of course, Ross was southern Australia’s Cessna dealer at the time (and the times were good). There’s a progress report in the Museum’s latest newsletter (http://saam.org.au) and regular updates on their Facebook page.

For having flown so many airplanes with his name on them, I knew very little of the man’s full history, so I’ll have to agree with Andrew — an excellent read. I love the ethic of the early aviation pioneers. They did it themselves, from building, maintaining and repairing the machine to teaching themselves to fly. Not to mention all the machinations of operating a business. Of course, they had a distinct advantage: no regulation. A ten cent bolt cost ten cents, not fifty dollars. They didn’t have the FAA, lawyers, or even much competition.

Airplane stories are almost always stories about people when you get right down to it. And these were some hardy folks. You can see a direct line of determination which comes down from the pioneers who ventured west across the Rockies in the most primitive covered wagons. That line seems to have vanished — or at least become quite faded — sometime in the late 20th century.

So true. Pioneers didn’t always build their own technology, but they made damn sure they could repair it. That holds from sailing ships to covered wagons to pioneering flights and more.

I firmly believe that everybody should know how to DO stuff, not just use (ie consume) stuff. (Modern equivalent – I put a new trackpad in my laptop the other week.)

As a matter of detail, I’m interested in how many aviators actually taught themselves to fly. I suspect it’s not as many as we might think (making Clyde Cessna extra special). After the first blush of flight, the earliest pioneers were pretty quick to set up schools… Tracing our ‘instruction ancestry’ would likely lead all the way back to one of the Wrights, Louis Bleriot, Glenn Martin, or a handful of others. What a thought!

It just goes to show what perseverance can do. Many of our youngsters today could learn a lot from people like Cessna.

Ooh, I’ll just leave that can of worms where you’ve opened it – but, absolutely, it’s a great tale of perseverance.

And pragmatism: Cessna always had his own back with the wheat farming. Perhaps Lesson #2 is ‘never get caught without options’.

– it’s the teacher in me I’m afraid! (Not wanting to tar everyone of the little darlings with the same brush of course!). Certainly a good lesson!

LOL. Feel free to use the article in your classroom.

A good idea!

What an amazing story of determination! And an excellent read. The quote is rather ironic for a man how accomplished so much in aviation! 😀 I wonder if he knew that 100 years from then they would still be making Cessnas . . .

I bet there were times when he didn’t think they’d be making Cessnas next week! But he pressed on anyway… When you think of all the aircraft companies that have disappeared without a trace – including Laird, Stearman, Travelair and so many others – Cessna’s survival is a real aberration. 90% good management and 90% good luck.

Thanks for sharing… Awesome story.

Thanks Peter. The research process was fascinating for me, so I’m glad you liked the end result. Keep enjoying airscape!