A few weeks back, the hugely admirable John Mollison posted a new Old Guys & Their Airplanes clip to accompany his finished illustration of F/L John Wilkinson’s Spitfire Mk.XIV.

Perhaps I should have that the other way around… Anyway, John’s post, clip and artwork reminded me that I had a pilot’s review of the XIV in my collection, and it seemed appropriate to share it.

Unlike a lot of Spitfire fans, the Griffon-engined Marks are by far my favourite. There is no apology about them – they are pointed and purposeful. Much as the Me.262 puts me in mind of a shark, the late model Spitfires look like a knife. No-one ever wrote ‘Born to kill’ on the side of a Spitfire XIV. There was no need.

The following piece dates from mid-1945, when ‘Indicator’ recorded his impressions of the Spitfire XIV for Flight magazine. His report appeared on newsstands on August 16th, the day after Japan’s surrender and 20 months after XIV had entered service.

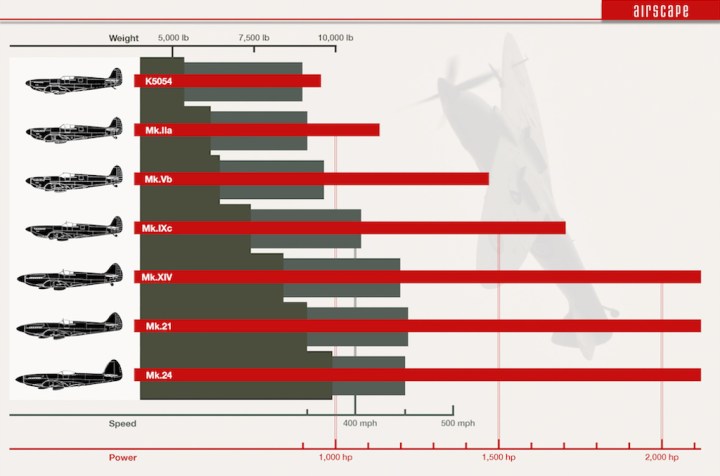

The XIV was a paradigm shift in the Spitfire lineage – arguably a new type, given the introduction of Rolls-Royce’s 2,120 hp Griffon V-12 plus the major structural and aerodynamic changes it required.

But, as the saying goes around Spitfires, ‘the wing is the thing’, and the XIV used the same elliptical wing as its forbears, despite the ever-increasing weight and power. And, as ‘Indicator’ found, that wing ensured the ferocious ‘new’ fighter remained very much one of the family…

From K5054 to XIV

Although the impetus of war has probably had a more marked effect on aeronautical development than any other form of engineering, it’s worth remembering that war only hurried pre-existing progress. The concentrated effort and expenditure has simply made aircraft development more rapid than it might otherwise have been.

Some of the best and most useful aircraft were largely or entirely developed during the preceding years of peace, and while the likelihood of war did accelerate their progress, the underlying knowledge was available and would undoubtedly have been applied to the design of civil and military types in due course.

As strongly as ever

This isn’t the place to produce a list of the military aircraft which were actually planned (or even experimentally flown) before the outbreak of war, but a few types can be safely given as examples.

From a point of view of British survival the most important two were, of course, the Hurricane and the Spitfire. The former, I believe, is still doing good work in the Far East. However, despite an almost incredible lease of life and the addition of cannons, bombs, rockets and extra tanks, it can now be considered as obsolescent. Meanwhile the Spitfire – in vastly different form, but basically still the Spitfire of 1938 – is going as strongly as ever. With twice its original power and nearly twice its early weight it has lost few, if any, of its original favourable flying characteristics.

Among the other aircraft which flew before the European war and were still being used in the same basic form for front-line operations at its end, I’d include the Douglas Boston* (an outstandingly good aircraft from the handling point of view), the Junkers Ju-88, and, if one can allow such extreme changes as have been made in layout and armament, the Boeing Fortress.

But the Spitfire holds a big lead in length of active service.

[ * The British version of the A-20 Havoc. I would also add the Me.109 and arguably the Lockheed P-38 to this list. —airscape ]

Savage and purposeful

Not that I’m suggesting the Spitfire XIV is merely a Spitfire I with more power and equipment. Gradual detailed development has made it vastly different; but the shape, structure and, most important of all, handling qualities have all remained much the same.

The pilot of a Mk.I or Mk. II might find the XIV something of a handful for a start, with its long nose, increased power and greater all-up weight, but he would soon accustom himself to the differences and would recognise the essential ‘Spitfire-ness’ of the ensemble. A few circuits would convince him that its somewhat savage and purposeful look, in comparison with the concealing elegance of earlier marks, is really camouflage for a set of comparatively mild habits.

Nevertheless, there might have been some justification for re-naming of the type from the introduction of the XIV. The additional power of the Griffon engine, and the fact that it turns the other way with a somewhat marked torque effect, makes both this and subsidiary marks ‘feel’ different – particularly while on and near the ground.

The majority of pilots, as they climb out of their first XIV after a long experience of the earlier marks, are inclined to say ‘Nice, fast, handleable flying machine – but it ain’t a Spitfire no more…’

Since Merlin-engined VIIIs, IXs and XIs were, and still are, in action on the fighting fronts, a change of name would still have left the Spitfire with the honour of being the war’s ever-young veteran.

Marks, Merlins and Griffons

For the assistance of those who have no reason to be au fait with the somewhat bewildering series of Spitfire marks – and for whom, perhaps, the use of Roman numerals involves a series of calculations rather like translating twenty-four-hour clock times into ancient English – it might be as well to sort out some of the later types. Excluding the little-used or obsolescent marks, the Seafire III, and the Spitfire V, VII, VIII, IX, XI and XVI are all Merlin-engined.

Merlin mark numbers have reached such heights that Roman numerology has had to be discontinued , and we can say that those Spitfires are powered, variously and according to their age and uses, by the Merlin 45, 55, 61, 63, 64, 66, 70, 71 and 266 – which last is the Packard-built 66 fitted to the XVI which is, in turn, merely a variation of the IX.

The VII and XI are P.R.U. (Photographic Reconnaissance Unit) types, and the VIII is, curiously enough, an ‘advanced’ form of the IX, with retractable tail-wheel and various other refinements. The apparent numerical inconsistency was caused by production arrangements.

Of the Griffon-engined marks, the first to appear was the XII – a low-level fighter with clipped wings. It had a four-bladed airscrew. Then there is the XIV, characterised by a five-blader and long nose to accommodate the Griffon 65’s two-stage, two-speed blower and intercooler. So much for the history and development lesson.

[ With large books dedicated to the subject, a more detailed explanation of the Spitfire ‘family tree’ deserves its own post in the not-too-distant future. —airscape ]

Into the cockpit

One’s first impression on lowering oneself into the cockpit of a Fourteen is that the layout, though still similar to that of the earlier marks, has been more seriously ‘organised’ to deal with all the extras which have been piled on to the Spitfire during the war.

For instance, the radiator flap and automatic blower-change test buttons, with the oil dilution button, lie alongside the fuel booster pump, navigation light and other switches in a neat row on the left. But, in such a comparatively small space, the impression of ‘busy-ness’ still remains – thanks to the installation of such items as gyro gun-sights and large-capacity priming pumps. It is only remarkable that everything can be found, and even seen with the naked eye, when so much must be confined in such a crowded setting.

A simple drill

The next impression follows the reflex movement of one’s left hand to grasp the throttle. This is of large proportions and with a relatively lengthy travel. The reason for this apparently disproportionate size is clear enough during the running up process, and even more so during the take-off.

With the earlier type of throttle, and particularly with cropped-blower Mark.Vs, the throttle movement to take-off boost was on the short side. This would never do in an aircraft with a critical run-up maximum and with such powerful torque effects during the later stages of the take-off. Still, a small fortune in Koffman cartridges must have been wasted by Mk.XIV newcomers who did not realise that the throttle should be set some two inches along the quadrant for starting.

Starting, as a matter of interest, is a first-time affair, hot or cold, for the pilot who knows his Fourteen and is prepared to be really generous with his throttle, both before and after releasing the cut-out.

Few aircraft are blessed with such a simple take-off ‘drill’ as the Spitfire XIV.

‘Trim, flaps, fuel and airscrew’ cover the essentials and, with automatic inter-connected constant speed controls, even ‘airscrew’ can be safely forgotten – and no one could be so blind as to leave the flaps down after ground-test since, from the very early days, there have been mechanical flap indicators to make a virtue of those necessities.

The mixture, of course, is fully automatic thanks to the Bendix-Stromberg carburettor. The radiator gills are also automatically operated, and there is no real need for the fuel booster pump under normal conditions.

Not going where it is pointing

‘T for Trim’ is, however, of moderate importance – especially as, in marked contrast to Merlin Spitfires, the Griffon swings the aircraft rather smartly to starboard during the early stages of take-off. So the order of the day is full port bias and, to remove all possibility of touching the airscrew tips, neutral or very slightly nose-heavy elevators.

And this is where the big throttle movement is thoroughly appreciated. Provided that the throttle is opened with reasonable circumspection and that the left foot is ready to exert plenty of initial pressure – assisted by a servo tab on the rudder – there is no reason for the Fourteen to deviate from its take-off course.

Once the boost is well up and the outfit under full sail, the tendency to swing is unnoticeable. In fact, after a smooth opening up to, say, zero boost, almost any further supply of power can be fed to the Griffon without personal hardship.

The only reason for limiting the boost before becoming airborne is to save precious tyre rubber. By virtue of torque reaction the Fourteen, while taking off, is certainly not going where it is pointing. Something has to be giving way when one can can enjoy a clear view of the runway over the starboard side while the beautifully cowled nose is aiming quite a few degrees off to port.

Obviously the tyres are balancing the difference, and it behoves one to use as little boost as is necessary to keep tyre wear to a minimum.

Boost and climb

I have no available figures (even if these could be published), but I would say that the Fourteen, in spite of its greater all-up weight, clambers skywards at its rated 9 pounds of boost just as quickly as the Nine does at its rated 12 pounds – and the Fourteen has a further 9 pounds in reserve for reasonably short periods.

Fighter climbing rates have become so preposterous nowadays that the figures are beginning to look like those for national debts. It will be sufficient to say that, at the recommended climbing boosts and speeds of modern fighters, most of one’s weight appears to be taken on the back of the seat!

While weaving tortuously through the dangerous maze of still-censored figures, we might try to satisfy the inevitable curiosity about airspeeds by using a few vague and harmless statements. At a fairly low cruising boost the Fourteen rumbles quietly along at very little short of 300mph IAS. At one critical height (not necessarily its best) a little slide-rule manipulation based on actual airspeed readings, position error and altitude shows the maximum to be a lot better than 400mph TAS.

That, I think, will be enough of figures for the present. One day, when the last of the King’s enemies have been confounded, we shall be able to relax in such matters.

[ Well that’s today, and the XIV’s top speed was actually 446 mph at 25, 400 feet. —airscape ]

Subcontractors and controls

One of the many difficulties in quantity production of fast aircraft concerns the tolerances and consequent discrepancies in components made by different firms all over the country. Minor variations must be expected, and these variations can make considerable differences where control surfaces are concerned.

There was a period when production Spitfires from some quarters were tending to show a ‘heavying-up’ of the ailerons. No doubt the reasons for this were fully understood and inescapable at the time, and the tendency did not develop but, remembering the characteristics of the intermediate marks, it seemed to be a pity. This trouble never appears to have affected the Fourteen, although some other problems, inevitable at modern diving speeds, had to be corrected during production testing.

Indeed, the later F.R. variety of clipped-wing Fourteen must have almost the nicest lateral control of any fighter type – which, when we remember the varied sources of wartime dispersed production, is a remarkable thing. And a Spitfire’s ailerons are never spoilt in the course of trimming adjustments, since these are always made by simply ‘dressing’ the trailing edges and shrouds.

Delight to aerobat

Consequently, the Fourteen is a delight for the acrobatically inclined. Even my own somewhat pedestrian repertoire is carried through with few blush-making divergencies from the ideal. Although, because of the considerable changes in directional trim required with varying speeds and boosts, one needs to be rather careful with the rudder.

Earlier marks have a plain adjustable trim tab on the rudder, which is on the heavy side, so in the intervals between adjusting this bias, one can afford to apply continuous or heavily increasing pressure without causing any violent results.

The Fourteen has a large adjustable tab which is, at the same time, of the automatic-servo type, and allowance must be made for this when instinctively correcting yaw. Continuously applying heavy pressure can result in over-correction – pedal reflexes being what they are.

Knowing little of the test and production history of the Fourteen, I’m prepared to be corrected when I suggest that almost its only handling fault concerns the slightly excessive power of this servo tab. Perhaps this is the price which must be paid to make take-offs easier, but it can also make it difficult to prevent the aircraft from weaving about through small angles, especially when diving in bumpy weather. And the Fourteen certainly does go downhill with no mean acceleration – to the delight of those on the ground with an ear for that particular kind of music.

When going really fast, it is advisable to use a constant speed setting slightly below the maximum permissible (2,750 to 2,775 rpm) since, if the airscrew is not perfectly matched to the particular airframe and engine, an uncomfortable vibration may be set up.

A slight reduction in propeller revolutions will usually smooth everything out in cases where this tendency appears.

Near the stall

The Fourteen appears to possess all the excellent slow flying characteristics of the earlier Spitfire marks. Its rate of sink near the stall is greater, but it still settles down in that magnificent level-keel manner which must have saved dozens of lives over the years.

Because of its greater all-up weight, the Fourteen’s tendency to ‘mush’ with any over-violent elevator movement at low speeds and small throttle openings is more pronounced, but this ‘mushing’ is also is dead-level and, if not caught on the throttle in time, merely results in a heavy landing.

Stalls may or may not be accompanied by buffeting (depending, apparently, on the condition of the wing-root fillet) but the stall itself remains quite harmless – unless energetically encouraged to be otherwise. Which is again rather surprising.

Closing stages

During the approach the forward view is a trifle less adequate than that of previous marks, but every Spitfire pilot develops his own method of providing himself with the necessary view – either by holding a slight skid, arriving in a continuous turn (when airfield conditions permit), or by maintaining excessive speed until the latest possible moment.

A power-on approach at 95 mph may look good in print and is perfectly safe from an aerodynamic point of view, but it is uncomfortable – though I know of few other aircraft which give one such a powerful sense of safe control while arriving in this manner, based more or less solely on a sense of ‘feel’.

Personally, I am strongly disinclined to land on something I can’t see clearly until the last possible second, so I prefer to hurry all the way in – nose well down and throttle well back, with the whole world in view over the front until the closing stages.

Once on the ground, of course, several feet of broad cowling is always an impediment to the view as one weaves and rubber-necks through a boulder-strewn dispersal. But it’s curious how, both on the ground and in the air, one learns how and where to look in order to see everything.

The Spitfire XIV is certainly no worse than her predecessors in this regard.

And however good the new Spiteful series may be, many pilots will be sorry when their Spitfires finally fade into obsolescence.

I’m not sure the development of that technology would have taken place without the war. The potential to develop it certainly would have been there without it, but it’d be like a car with no fuel in the tanks: it would never go anywhere.

You can see the same thing taking place today. Could we fly business jets and airliners supersonically? Could we go back to the moon? Colonize it? Journey to Mars? Could we have limitless renewable energy for the whole planet? Sure. But it’s extremely hard, time consuming, risky, and expensive. At the moment, there’s insufficient motivation to accomplish them.

WWI and II were existential crises. Either the advanced tools and technologies were going to be developed, or the society itself would cease to exist. It’s amazing what mankind is capable of when the proper motivation lights a fire under our collective posterior.

It’s a terrible dilemma, isn’t it? Obviously progress requires some kind of impetus, and the more powerful the better. Before World War 2, burgeoning demand was certainly driving progress in civil aviation – the Focke-Wulf Condor, De Havilland Albatross and Lockheed Constellation were all sleek, pre-war designs. Similarly, the glory days of air racing in isolationist America created some incredible single-seat aircraft and broke countless records. The NACA made a vast difference at this time too…

The Cold War was just as vital to ongoing development. Both sides relied on Nazi know-how to get into space. But let’s not forget that all Boeing airliners trace their heritage to the military’s need for a jet tanker, and the B-47 bomber before that.

But NONE of that progress could have happened without aviation’s true crucible, World War One. Those four years were absolutely formative, and it almost beggars the imagination to think what contemporary aviation would look like without those original knights of the air (and the visionary technicians behind them – Sopwith, Fokker, AV Roe, Bristols, SPAD, Nieuport, Le Rhone, Rolls-Royce…)

If we’d had 100 years of peace, perhaps aviation might still be a precarious playboy sport of linen and sticks.

There’s a great line in Orson Welles’ ‘”The Third Man” where protagonist Harry Lime says “Necessity isn’t the mother of invention. War is.” Real truth resonates.

Mind you, profit has proven a pretty good substitute too.

The question is, how can we light that kind of fire under contemporary GA?

The range of Spitfire marks is a minefield for the uninitiated and one that baffles most people (in using me!). It is a beautiful aircraft in whatever guise it is, and frankly a world beater in engineering. I doubt many other models will ever come close to it. A bit like the Beatles of the music world.

Absolutely – although I think you meant The Rolling Stones of the music world. ;-)) Anyway, it’s a minefield I’m planning to run through in a future post. (The Spitfire minefield, not the music taste one – I’m backing out of that as of right now.)

Ha ha – diplomatically speaking, whoever it may have been they were one of a kind (like the Spitfire).