They were ex-fishermen mostly, but to say they’d chosen a safer life ashore would be a lie.

The Surfmen of the 19th century United States Life Saving Service were the forerunners of today’s US Coast Guard, a service that’s still renowned for helping aviators in need.

History’s first ground crew

A hundred years ago, those brave men lived in windswept stations along the worst stretches of the Atlantic coast, having abandoned the rhythms of a fishing life for one of constant readiness, putting to sea only when conditions were at their worst.

They saved the lives of many sailors. But in 1903, for the first time ever, they came to the aid of aviation too.

Orville and Wilbur Wright would conquer the air with ingenuity, determination, and patience. But they couldn’t have done it without the men of the Kill Devil Hills Life Saving Station – history’s first ground crew.

It was one of them, Surfman John T. Daniels, who took that most famous aviation photo of all.

Wilbur had set up a heavy Korona-V glass-plate camera on December 17th, 1903 and, when everything else was ready, asked Daniels to squeeze the rubber shutter-release bulb as the Flyer reach the end of its launch rail. As ever, Daniels happily did as his visitor from Ohio asked.

A hospitable people

When the Wrights first went searching for a location with small hills, open beaches and strong, steady winds, the US Weather Bureau suggested Kitty Hawk, NC. So the brothers wrote to the local postmaster, who assured them the sands around Kill Devil Hills were exactly what they wanted – windy, wide and clear.

That was one William J Tate (whose wife was officially the postmaster/mistress at Kitty Hawk). He wrote the Wrights:

“If you decide to try your machine here & come, I will take pleasure in doing all I can for your convenience & success & pleasure, & I assure you you will find a hospitable people when you come among us.”

The brothers duly arrived at his door on the morning of September 13, 1900 and Tate made them welcome. Soon, Orville and Wilbur were assembling a glider on the Tates’ front lawn and using Mrs Tate’s sewing machine to stitch the last of the fabric covering.

More than 1,000 experiments

They then flew the craft as a kite over the Kill Devil Hills, four miles south of Kitty Hawk. The conditions were everything they’d hoped for, and they were obviously delighted by the friendly support and enforced discretion of the isolated community.

The Kitty Hawk locals were rather less impressed. Tate would later recall:

“The mental attitude of the natives toward the Wrights was that they were a simple pair of harmless cranks that were wasting their time at a fool attempt to do something that was impossible. The chief argument against their success could be heard at the stores and post office, and ran something like this: ‘God didn’t intend man to fly. If He did He would have given him a set of wings on his shoulders. No, siree, nobody need not try to do what God didn’t intend for him to do.’

“I recall, not once, but many times, that when I cited the fact that other things as wonderful had been accomplished, I was quickly told that I was a ‘darned sight crazier than the Wrights were’.”

Still, it was a friendly relationship and the ‘harmless cranks’ left their glider behind when they went back to Ohio. Orville would later write to Tate:

“As I remember, when we came back to Kitty Hawk in 1901, Irene and Pauline were wearing dresses made from the sateen wing coverings of our first machine.”

Having learned much from the successes and failures of their 1900 experiments, the Wrights returned to Kitty Hawk in 1901 and 1902, bringing ever-larger and more refined gliders and building a semi-permanent shed to protect them at big Kill Devil Hill.

By the end of 1901 they’d uncovered the many shortcomings of the aeronautical knowledge they’d been using. By 1902, they’d built a larger and more advanced glider – one that would, at last, be able to lift them into the air.

And that year, through more than 1,000 experiments, they taught themselves to fly.

A priceless friendship

When the Wrights returned to North Carolina in September 1903, they were ready to fly a powered machine. While they waited for it to arrive, they set about putting their old shed in order and building a new, larger one next to it.

Inevitably, natural hospitality and curiosity brought Surfman Adam Etheridge calling. He visited the Wrights’ camp with his wife and child, opening a priceless friendship between the brothers and the crew of the Kill Devil Hills Life Saving Station.

The keeper in charge was Captain Jesse Etheridge Ward. A native of the Outer Banks, he was born on nearby Roanoke Island in 1856 and worked as a fisherman until he joined the service in 1880. He and his station crew – Surfmen Will S. Dough, Adam D. Etheridge, Bob L. Wescott, John T. Daniels, Tom Beacham, and “Uncle Benny” O’Neal – were as intrigued as anyone by the ‘cranks from Ohio’. On their lonely stretch of coast, Wilbur and Orville were about the only entertainment going.

As the Wrights demonstrated their growing proficiency and, more importantly, a constant kindness and respect toward the locals, they earned the friendship of the Life Savers. Captain Ward agreed to help where he could, and cleared his crew to provide assistance whenever duty allowed.

Soon the Surfmen were an integral part of the preparations for powered flight. Etheridge would report:

“We really helped around there hauling timber and carrying mail out to them each day… When we got through cleaning up around the [Life Saving] station some of us would take the mail out to them, staying around and helping around until maybe near dinner time. In pretty weather we would be out there while they were gliding, watching them.

“Then after they began to assemble the [powered flying] machine in the house they would let us in and we began to become interested in carrying the mail just to look on and see what they were doing. They did not mind us at all because they knew where we were from and knew us…”

The Life Savers also went to collect or buy food for the brothers, who would sometimes invite them to dine. According to the Life Savers, the Wrights were both excellent cooks.

Hardy assistants

By November, the Wright brothers had come to count on their hardy assistants from the Kill Devil Hills Life Saving Station. They started hanging a red flag from the workshop roof when they wanted help, and any available Life Saver would happily oblige. The Surfmen aided in the assembly of that first Wright Flyer, along with carrying the machine, launch rail and other equipment to and from the camp.

As their date with history approached, Wilbur and Orville suffered several frustrating setbacks. Most serious was the continual failure of their propeller shafts. Eventually, on November 28th, Orville took the old shafts back to Dayton to make a pair of replacements from solid tool steel. Captain Ward ferried the aeronaut (and the broken shafts) across to the the mainland in his launch.

Orville returned with the new shafts late on Friday, December the 11th and the machine was ready by the next afternoon. However that Saturday was uncharacteristically calm and no flights were attempted.

To their friends and ground crew

“Monday, December 14, was a beautiful day,” Orville wrote later, “but there was not enough wind to enable a start to be made from the level ground about camp. We therefore decided to attempt a flight from the side of the big Kill Devil Hill.”

The brothers hung out the red flag and before long Daniels, Westcott, Beacham and Dough had arrived to help set everything up on the hillside some 400 metres away. Two local boys and their dog also turned up to watch.

Wilbur and Orville tossed a coin to see who might become history’s first powered pilot. Wilbur won. But with the calm air the Flyer was unable to gain enough airspeed on the launch rail – it rose sharply, stalled and crashed left-wing down onto the sand. Wilbur cut the engine and climbed out unhurt, but the Flyer was finished for the day.

They repaired the damage on the 15th, but the 16th again proved too calm for flying.

The 17th dawned cold and clear, with a steady 22 knot wind blowing off the sea. Again, the Wright brothers hung out a signal to their friends and ground crew at the Life Saving Station. Adam Etheridge, John Daniels and Will Dough were off-duty that morning and promptly answered the call.

Meanwhile, Bob Wescott, who was on duty at the station and preparing the midday meal, ran to the top of the lookout tower to follow events through a spyglass. He became such an engrossed witness to history that he forgot about his pancakes, and they were burned black!

‘Laugh and holler and clap’

Ever fair-minded, the Wrights knew it was Orville’s turn to take the controls after Wilbur’s failed attempt on the 14th. Once the men had helped set everything up and the motor was started, the pair shook hands.

One Surfman noted how “…they held on to each other’s hand, sort o’ like two folks parting who weren’t sure they’d ever see one another again.”

While Orville climbed into the pilot’s cradle, Wilbur set up the camera and told Daniels when and how to take the hoped-for photo. He then shouted for the other Surfmen “not to look too sad, but to …laugh and holler and clap… and try to cheer Orville up when he started”, before going to steady the Flyer’s wingtip for takeoff.

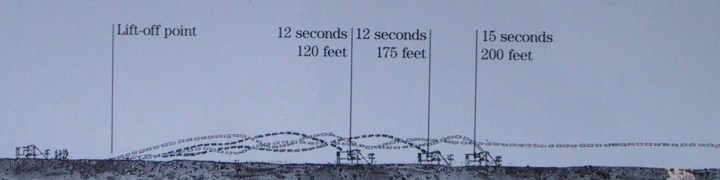

At 10:35 that morning, as the wind blew and Wescott’s pancakes burned, Orville and the Wright Flyer lifted into the air after a shorter-than-expected run and flew, under control, for an historic 120 yards. With a recorded head-wind of 35 feet per second, the brothers claimed an air distance of 540 feet.

All rushed to save it

The Surfmen then helped bring the Flyer back to the rail for a second flight. At 11.20, Wilbur took off and covered 175 yards against a slightly lesser wind. By 11.40, the men had everything ready for Orville to fly again. This time, after 15 seconds and 200 yards, a sudden gust tested all the skill he’d learned from flying their gliders, and he was (barely) able to bring the machine down in one piece.

Again, the Surfmen helped bring the Flyer back to the launch point. Right on noon, Wilbur took off and flew for a total of 852 feet over 59 seconds, before pitching down hard onto the sand. Despite damage to the foreplane support, this flight convinced the Wrights of their success and they expected to have the machine repaired for further flights in a day or two.

The Kitty Hawk wind, though, had other ideas. A sudden gust lifted the machine and they all rushed to save it. Wilbur grabbed the front, while Orville and John Daniels got hold of the wing supports from behind. As the Flyer continued to lift, both Wilbur and Orville were forced to let go.

But John Daniels had been trained as a Surfman. He held on.

“I found myself caught in them wires,” he remembered later, “and the machine blowing across the beach heading for the ocean, landing first on one end and then on the other, rolling over and over, and me getting more tangled up in it all the time. I tell you, I was plumb scared.”

Orville recorded that Daniels was thrown head over heels inside the machine, and got badly bruised as he fell against the framework, chain guides and motor. Luckily he wasn’t more seriously injured, but the Flyer was finished.

The Life Savers now helped Wilbur and Orville carry the tangled wreck back to the shed, where they spent the next few days crating it up and despatching it back to Dayton to be repaired over the winter.

Those tough Outerbanksmen

The Wright Brothers were enormously grateful to those tough Outerbanksmen who helped them make history. Before they left that winter, they presented the Life Savers with a photo of themselves in front of their Kill Devil Hills Station, along with leftover equipment from the camp and five dollars toward a Christmas dinner. They also presented a Wright bicycle to John T Daniels, who used it to patrol the lonely beaches around Kitty Hawk for years.

The Wrights received more help from their friends when they returned to the remote discretion of Kitty Hawk in 1905, and again in 1908 to test their prototype two-man Flyer for the US Army.

Although time has forgotten them – and quite unjustly, I might add – those tough, brave forerunners of the Coastguard were lionised by the press during early anniversaries of December 17th, 1903.

Postmaster (or, more correctly, Postmistress’ spouse) William Tate helped place historic markers around the site for the 25th Anniversary celebrations in 1928. And, in December 1953, the stalwart John T Daniels overcame a lifelong fear of flying to join another aviation pioneer, Coast Guard Helicopter Pilot #2 Lieutenant Stewart Graham, above the newly re-designated Wright Brothers National Memorial.

He made the flight in a US Coastguard Helicopter. . . Wilbur and Orville Wright would certainly have approved.

I am deeply indebted to Scott Price, Deputy Historian, U.S. Coast Guard Headquarters in Washington, DC, for his original article on the surfmen of the Outer Banks, and for his permission to draw on his research for this article.

Please visit the USCG History site to read more.

See, this is why I love Airscape: you connect the dots in a way I’ve never seen.

I knew about John T. Daniels being the world’s most underappreciated photog, but never would have associated the success of the Wrights with the U.S. Coast Guard.

I know. Amazing aspect of history, right? All kudos to Scott Price at the USCG HO.

Fascinating post! I’m not sure why I put off reading it for so long. 😛

Could I request a blog post about the Alberto Santos-Dumont first in flight claim and why the Brazilians think he was the first in flight?

Thanks for the feedback Hannah. There is one article about Santos Dumont here (https://airscapemag.com/2016/04/03/santos-dumont/) but that is more about his ballooning… He was certainly a fascinating character. He’s generally credited with the first successful powered flight in Europe in 1906, which he managed without reference to the Wright brothers. Other uncontrolled hops had been made before, and his was barely controlled, but there you are. Exactly why the Brazilians want to believe he made the first flight anywhere will need a little more investigation…

I just found this article. Very well done and appreciated. Bob Wescott is my 2nd great-granduncle (my 2nd great grandfather’s brother. They were both US Lifesavers) Family lore is that my 2nd great grandfather was napping during the actual first flight. 😉 John Thomas Daniels was Bob and John Thomas Wescott’s nephew. It’s funny, I have a copy of that 1902 photo that was in my great-grandmother’s things. I never knew the Wright Brothers were in it. I thought it was of Lifesavers.

Thanks for your comment, Marlee. It is always a thrill when one of my articles helps someone to connect with an ancestor and learn more about the things they accomplished.