Back in the days when aircraft designers used slide rules and genius, one of Britain’s best sat down to address the widening gap between his country’s front-line fighters and those of her arch-rival Germany.

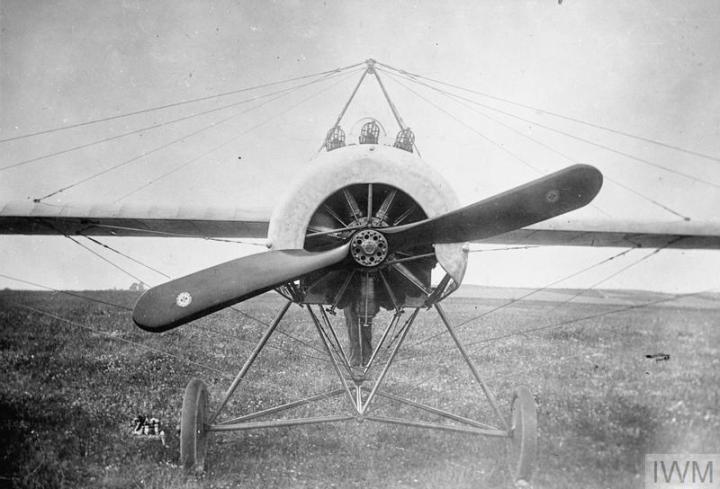

As a private venture project, he was free to pour everything he knew about air fighting and aerodynamics into his design. From its radically streamlined fuselage to its elegantly curved wing, the little fighter was created to give Britain a desperately needed edge.

You think you’ve heard this story before – but don’t be fooled. The designer is not RJ Mitchell and his fighter is not the Supermarine Spitfire.

That said, the parallels are arresting, even if the outcome was vastly different.

The year is 1916. The designer is the Bristol Company’s Captain Frank Barnwell.

Fokker Scourge

By the spring of 1916, air warfare had come of age. Gone were the days of waving at enemy observation crews or taking haphazard shots with a service rifle.

Machine guns had become standard hardware on the linen and wood machines. Rene Fonck had fixed deflector plates to his propeller and blasted Germans from the sky in surprise nose-first attacks. From there, both sides quickly developed mechanical interrupter gears but, first to the fight, the deadly Fokker Eindecker began cutting swathes through Britain’s inexperienced observer crews in the seven months from August 1915.

The term ‘Fokker Scourge’ would be created by British media as a political football later in 1916, but it perfectly described the deadly effect of Anthony Fokkers purpose-built fighter in the hands of experten like Boelke, Immelman and Buddecke.

In something of a panic

In something of a panic, the British War Ministry turned to the private sector for help. The Bristol Company arranged for its pre-war chief engineer, Frank Barnwell, to be released from the Royal Flying Corps to take charge of their response.

Barnwell had designed the Bristol Scout, which was beloved by early service pilots, before he enlisted. On his return to Bristol, he began by correcting the faults he saw in the Royal Aircraft Factory’s new R.E.8 observation plane. His resulting Bristol R.2A would evolve into the excellent Bristol F.2b – arguably the world’s first true multi-role fighter. Then he turned his attention to a single-seat Fokker killer.

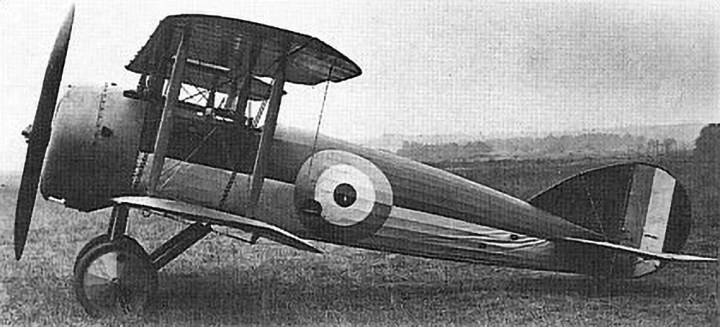

To say the resulting Bristol M.1 (M for monoplane) was ahead of its time would be an understatement. Like the Spitfire 30 years later, its aerodynamic modernity shocked the bureaucrats who were expected to pay for it.

Monoplane

For one thing, the new fighter was a monoplane. Following several fatal crashes (and a temporary ban) in 1912, the powers-that-be had a distinct dislike for monoplanes. They didn’t trust them. Biplanes were stronger and easier to understand. All the engineering was on the outside.

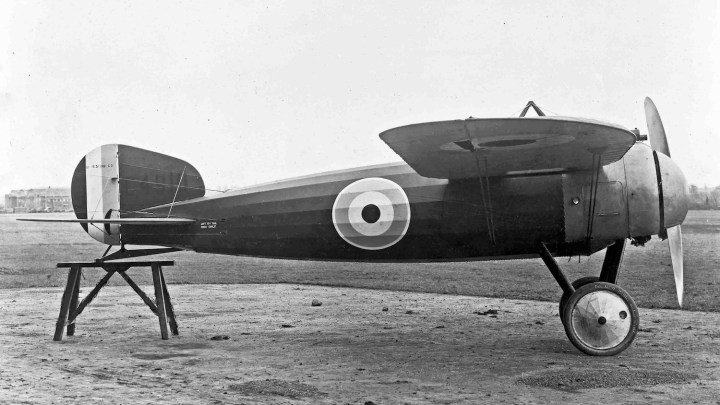

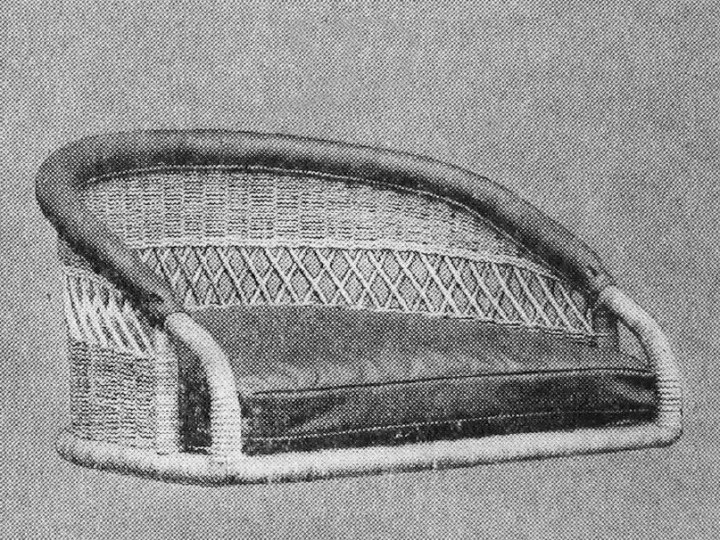

It was also round. At a time when aircraft fuselages were rectangular, Barnwell had enclosed his conventional braced box construction with a secondary framing that faired its cross-section from nose to tail.

Whether this streamlined fuselage was a true clean-sheet design is an open question.

Let’s close it right now: Nope.

Elements of the M.1 came from all over – the pilot’s controls were lifted wholesale from the Bristol Scout; and the horizontal stabiliser used an internal structure that Barnwell had sketched for the prototype Scout but which had been replaced by something more conventional for production.

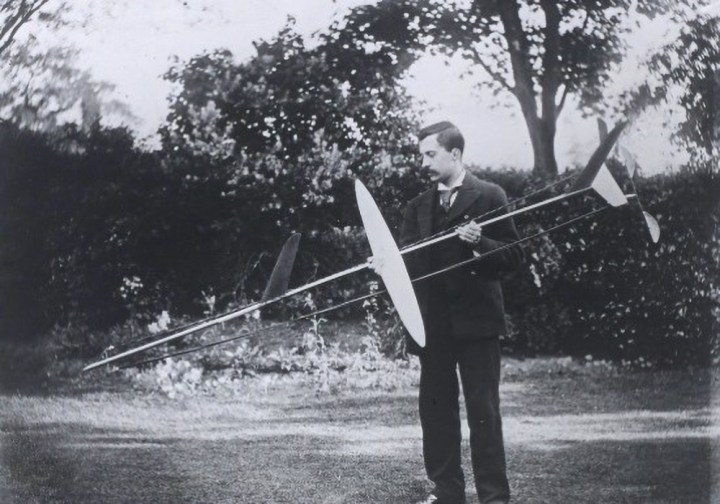

But much more significant is the striking family resemblance (pun intended) to ‘The Barnwell Bullet’, designed by Frank’s elder brother Harold Barnwell in late-1914.

Barnwell’s Bullet

Harold was Chief Test Pilot at Vickers and had built his ‘Bullet’ biplane in secret, using Vickers’ workshop facilities and a Gnome Monosoupape engine lifted from company stores. Unfortunately the undercarriage collapsed at the end of his first test-flight in early 1915, and the machine was wrecked. Barnwell was lucky to get away uninjured and still employed.

Vickers had their designer Rex Pierson re-draw the aircraft with enlarged elevators for improved handling, and two examples were built as the Vickers E.S.1 (E.S. for Experimental Scout). By all accounts they were extremely fast for the time, with a top speed of 118 mph (190 km/h) and were capable of gaining height on a loop begun “off the top”.

Frank and Harold had always been close, and had been building aircraft together since 1905. Did they collaborate on the Bullet’s design, while Frank was enlisted in the RFC and therefore a free agent? Or did Harold simply discuss the details of his fighter with Frank, as brothers sharing their passion for aircraft design?

Either way, rather than whipping up a splendid new fighter in a matter of months, Barnwell had undoubtedly been accumulating the elements of his ideal single seater for at least a year.

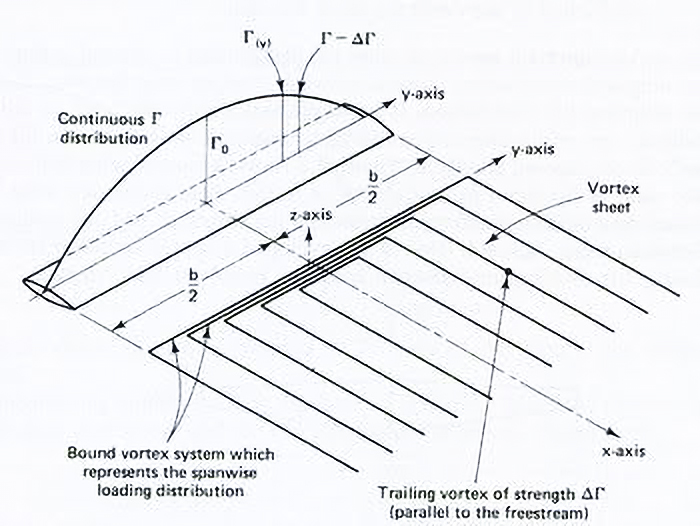

Pre-empting Prandtl

Just as troubling as the monoplane format, and just like the Spitfire, the M.1’s curving wing looked impossibly complicated, costly and time-consuming to produce. Apart from the obligatory left-right symmetry, no two ribs were the same.

Behind this complication, however, was a work of real genius.

While numerous designers had already modelled the planform of a bird’s wings, Ludwig Prandtl would not publish his seminal work on an ideal elliptical lift profile until 1919. Interestingly, English polymath Frederick W Lanchester had pre-empted Prandtl with the same concept – but not the same mathematical rigour – in 1906. And Lanchester’s second volume on aerial flight had dealt with stability, a topic on which Frank Barnwell would later publish his own text.

To really establish Lanchester’s credentials, he also patented the contra-rotating propeller in 1909!

While most of the world was dumbfounded by Lanchester’s thinking, it’s possible Frank Barnwell sought him out too, or at least spent long hours absorbing his innovative concepts.

Vicious stall behaviour

One subtlety of Prandtl’s lift theory is that his ideal elliptical wing should have no twist.

Unfortunately that’s a short-cut to vicious stall behaviour, where the loss of lift propagates from the wing tip rather than the root. The Spitfire’s aerodynamicist, Bev Shenstone, was forced to compromise his famous wing design by including a washout to negate this tip stall danger.

Barnwell, on the other hand, designed the washout into his wing aerodynamically – reducing his airfoil’s natural angle of incidence as it progressed outboard along each spar while keeping the bottom of the wing completely flat. It was a brilliant solution.

He also minimised drag wherever he could – from the streamlined bracing wires and ovoid cross-section of the pylon that held them, to the addition of small aluminium cups to fair over the attachment fittings on the wing surfaces.

Nothing was exposed to the slipstream that didn’t need to be there. The design ethos was closer to a 1930s racer than a WW1 fighter.

Top speed

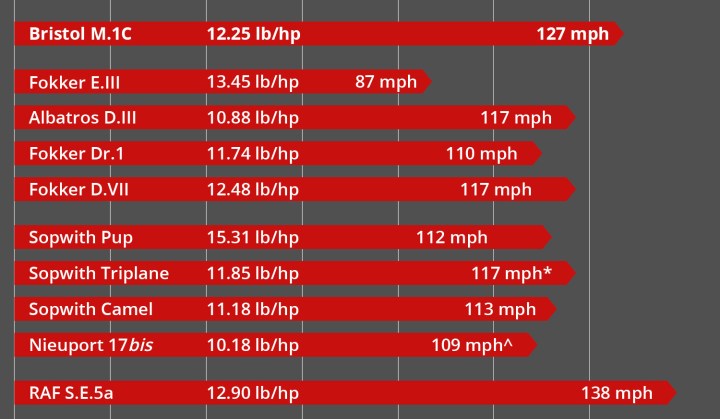

It worked. In tests at the RFC Central Flying School, the M.1A booked a top speed of 127 mph* (204 km/h, 110 knots) – 40 mph or nearly 150% faster than the Fokker E.III Eindecker it had been designed to tame. In the same tests, the aircraft climbed to 10,000 feet in an astonishing 8.5 minutes. (In 1918, British ace James McCudden VC climbed a production M.1C to the same altitude in only 7 minutes!)

In fact, it could have held its own against most Allied and Central Powers fighters for the remainder of the war. The formidable Albatros D.III of ‘Bloody April’ 1917 and its D.V successor were both slower than the M.1. The Royal Aircraft Factory S.E.5a (the ‘Spitfire of the Great War’) was only 8 mph faster when it entered service. Even the excellent Fokker D.VIII of 1918, another monoplane, could only just match it for speed.

Unfortunately, those comparisons would remain all but hypothetical.

*Accurate airspeeds for the M.1 are elusive. The M.1A trial was not conducted below 6,5000 feet and the later trial of M.1C C4902 (with full war load) only reports speeds at 10,000 (106 mph), 13,000 (102.5 mph) and 15,000 feet (99.5 mph). As the aircraft was losing 1.3 mph per 1,000 feet between those altitudes, we could project downwards to add 13 mph at sea level. i.e. 106 = 13 = 119 mph.

However, the test pilot added a note to the final report saying ”The figures given above for the speed trials are probably 5 mph too slow, as they were obtained from the readings of the air speed indicator corrected for density only.” Adding 5 + 119 takes us to 124 mph, with a full war load and that simplistic estimation down from 10,000 feet.

One ace

The possible reasons why the Bristol M.1 was not put into large scale production are many and varied – and fodder for a whole separate post.

In the end, the War Office begrudgingly gave Bristol a contract for 125 M.1C aircraft – the production version that included refinements derived from service tests. Of those, just 30 or so were dispatched to frontline squadrons from late 1917, distributed piecemeal across France (just 1 aircraft), the Balkans, and the Middle East.

The type only made one ace, Captain Frederick Dudley Travers DFC of No. 150 Squadron, who won five of his nine victories in an M.1C while based in Macedonia. The quintet took him just two weeks from the beginning of September 1918 and included two Albatros D.Vs plus a vaunted Fokker D.VII. Not bad for an aircraft designed for conditions on the Western Front two years earlier!

But ultimately, the M.1C entered history as one of those fabled woulda, coulda, shoulda designs.

Hallmarks of greatness

It had all the hallmarks of greatness: For one thing, it demonstrated remarkable development potential – including the evaluation fleet of four M.1Bs performing admirably with 110 hp (82 kW) Clerget 9Z, 130 hp (97 kW) Clerget 9B and 150 hp (110 kW) Admiralty Rotary A.R.1. rotary engines.

Twelve M.1Cs were shipped out to Chile in the second half of 1918, in part payment for two battleships had been requisitioned off the slipways by the Royal Navy. One of these was used by Chilean aviator Lt. Dagoberto Godoy to make the first flight over the Andes on 12 December 1918 – a feat that was still alarming mail pilots like Antoine de St. Exupéry ten years later.

Post-war, one M.1D sported the new 140 hp (104 kW) Bristol Lucifer radial engine for racing and, in Australia, an M.1C was re-engined with a series of progressively more powerful de Havilland Gypsy inline motors, stripped of its fuselage fairing, and raced successfully into the mid-1930s.

On that basis, the fighter’s most obvious shortcoming – that it only carried one Vickers gun when two was de rigeur by 1917 – should have been easily remedied. If they’d been more widely deployed, I’m sure that would have been swiftly fixed in the field.

Ringing endorsement

Instead, the most ringing endorsement of Barnwell’s far-seeing design was simply that examples seemed to pop up in every school of advanced training and air fighting in Great Britain, where they were inevitably the brightly painted and much beloved mount of the country’s best air combat instructors. Enough said.

Unlike the Lords and bureaucrats in Whitehall, those professional dogfighters recognised the key benefit of Barnwell’s fighter: That speed is energy – and energy is king.

So would the M.1C’s far-sighted prioritisation of speed have changed the war? Of course not. But it could have accelerated the evolution of air combat by a decade or more.

Where are they now?

Over 100 years later, M.1Cs are vanishingly rare. As a family comparison, there are more original Bristol F.2b survivors than there are genuine and replica M.1Cs combined.

- Incredibly, a reasonably original example survives in Minlaton, South Australia. It is the above-mentioned racer that was bought from the Disposal Board by demobbed RAF air fighting instructor Captain Harry Butler, clearly for his own continued enjoyment. Its current originality is more complex than the Theseus Ship Paradox, but its story is well documented and definitely worth a separate post.

- The RAF Museum at Cosford is home to a replica built from original drawings by Rolls-Royce engineer and historic aircraft constructor Don Cashmore between 1983 and 1987. It was flown for a total of 60 minutes (over three flights) using a 165 hp (121 kW) Warner Super Scarab radial engine, before being sold to the Museum and fitted with an original Le Rhone for display purposes. Its striking dragon colour scheme is replicated from a photo taken at the Central Flying School, Gosport.

- The Chilean Museo Nacional Aeronáutico y del Espacio (MNAE) in Santiago is home to two replicas. The first was built by AJD Engineering (now Hawker Restorations) in the UK between April 1988 and March 1989, on commission for the Chilean government. I suspect this project used many drawing sourced from Don Cashmore. It was built to be accurate and airworthy but, again, was only flown a couple of times behind a 145 hp (107 kW) Warner Super Scarab before being placed on permanent display.

- Museum staff then used that replica as a template to build a second non-flying replica, which was completed with a Gnome Omega from the museum’s collection inside its strangely over-long cowling. The Omega has since been removed and installed on a replica 1912 Voisin.

- Finally, Northern Aeroplane Workshops in Yorkshire, UK, built a very faithful replica for the Shuttleworth Collection at Old Warden, completing it in 1997. This project appears to have hoovered up virtually all the drawings used by previous replica builders and is probably the most accurate of them all. Powered by an original Le Rhone 9J, it is also the only flying M.1C anywhere.

One more thing

Oh yeah. And my interest in the Bristol M.1C is more than academic – I’m also working to increase their number by one.

That’s right, my build project is one of these.

It is a long, long process. I started researching the still-available drawings 17 years ago. While there are one or two things I don’t know even now, I’ve accumulated enough information to be confident I’m building a millimetre-accurate example. And the pile of parts I’ve made is beginning to grow.

Don’t expect to see it flying any time soon though. As I recently saw it described to an audience raised on Vans RV kits, “with plans aircraft, first you have to build the kit – then you build the airplane”.

Except I’ve had to investigate the airplane, then redraw the plans, then figure out the kit, and then proceed as above. Lucky I enjoy solving problems!

Meantime, I’ll continue to serve up articles about this intriguing fighter – including analysis of the RFC’s lacklustre reception, some interesting aspects its design and construction, a deep dive into the actual originality of that ‘only original example’, a proper look at Frank Barnwell’s career and, of course, ongoing build updates.

I hope I’ve sparked your interest. And I look forward to having you along.

Congratulations. I have two black and white framed photographs of Wilbur and Orville Wright flying the Flyer at Kittyhawk on my desk. Dreams can come true. Keep at it. I also have an original screenplay on the early years of John Flynn’s dream of the world’s first Aerial Ambulance, but can’t get a producer interested, yet. Keep at it.

Thanks Russell. Best of luck with your John Flynn project – it is super-important that his story isn’t forgotten. Whenever the hill looks too big or steep, I like to stop and watch One Six Right, the making-of documentary for Brian Terwilliger’s seminal One Six Left. It’s a fantastic account of the power of patient persistence. Check it out some time. (I may love it more than One Six Left itself!)

I’m impressed enough by those that assemble a pre-punched, match-drilled kit from Vans. But a scratch-built, WWI bird like the M.1C? Wow.

I’d love to hear a bit about why, out of all the possible airplanes you could choose to fabricate, you selected this one.

The rudder gear looks impeccable. If the rest of the aircraft is of that quality, I think you’ll have a winner on your hands. What are you thinking of for an engine?

Sorry for all the questions. A very exciting project!

–Ron

I get the feeling that you like to ‘bite off more than you can chee and the chew like crazy’! 🙂