Beyond the limits

In part one of this series, artists of the early 20th Century imagined voids in their illustrations of primordial airliners to demonstrate the comfort and complexity of mankind’s latest leap forward.

By the late 1930s, however, and certainly by the end of World War II, aviation was becoming vastly more sophisticated. Engineering, on the other hand, remained tethered to the two-dimensional blueprints of another age.

Interpreting that gap fell to a cadre of artists who could construct and assemble the various components of an airliner in their heads, then imagine it all onto their drawing boards. Their talent would have made the Renaissance masters gasp.

Today, 3D CAD and AI have made sophisticated engineering renders a near print-on-demand commodity. When these aircraft were state of the art, though, the drawings were art. So, as you drink them in, try to carry a sense of just how remarkable the aircraft were to the original audience and – more importantly – just how impossible these views actually are.

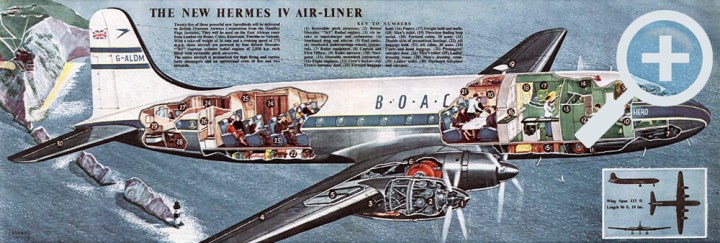

1950 BOAC H.P.81 Hermes IV

I’m always impressed by how quickly the British aviation industry, which had no commercial aircraft output during the war, managed to transition back into civil aviation at the end of hostilities.

I’m not talking about their clunky Avro Lancastrian-type stopgaps either. Starting with what could be viewed as the highly optimistic Brabazon Committee meetings in late-1942, plans were laid to re-establish British civil aviation with a range of airliners that would meet the needs of the nation and (what was left of) the Empire, avoid having to buy foreign i.e. US products with non-existent capital, and be so innovative as to swiftly restore British strength in the global marketplace.

The vastly unlikely strategy very nearly succeeded, spawning the world’s largest airliner, the world’s first turboprop airliner and the world’s first commercial jet airliner.

In reality, the Handley-Page H.P. 81 Hermes IV, and the Hermes variants before it, were not particularly cutting edge. They were, essentially, a British answer to the Douglas DC-6 and other piston propliners in the same class.

The design’s origins go back to April 1944, when company founder and director Frederick Handley-Page decided to focus on a new transport project for the RAF.

That project lead to the H.P.67 Hastings, and the civilian H.P.81 Hermes proceeded pretty much in parallel, with the civilian airliner flying for the first time in December 1945. However, a chequered development phase and subsequent design improvements meant the definitive Hermes IV did not enter service until August 1950.

Powered by four 2,020 hp (1,510 kW) Bristol Hercules radial engines and capable of carrying up to 82 passengers, the type was only used by launch customer BOAC until 1952, before slogging on with secondary, charter and freight operators until 1964.

G-ALDA was actually the second H.P.81 built and was to go to BOAC named Hecuba. That explains her role in the customary new-airliner publicity illustration. However, not having some of the weight saving modifications of later airframes, BOAC refused to accept her for actual service and she immediately went to an itinerant existence with charter operators.

Ironically, G-ALDA still ended up being the last Hermes in civil use, serving with two-aircraft charter operator Air Links Limited from 21 December 1962. She was then flown to Southend a week later, where she was broken up during March 1965. Civil aviation can be a brutal business. (Note: This para has been updated from an earlier version, which stated G-ALDA was scrapped on 22 December. Thanks to Mike Cain for the correction.)

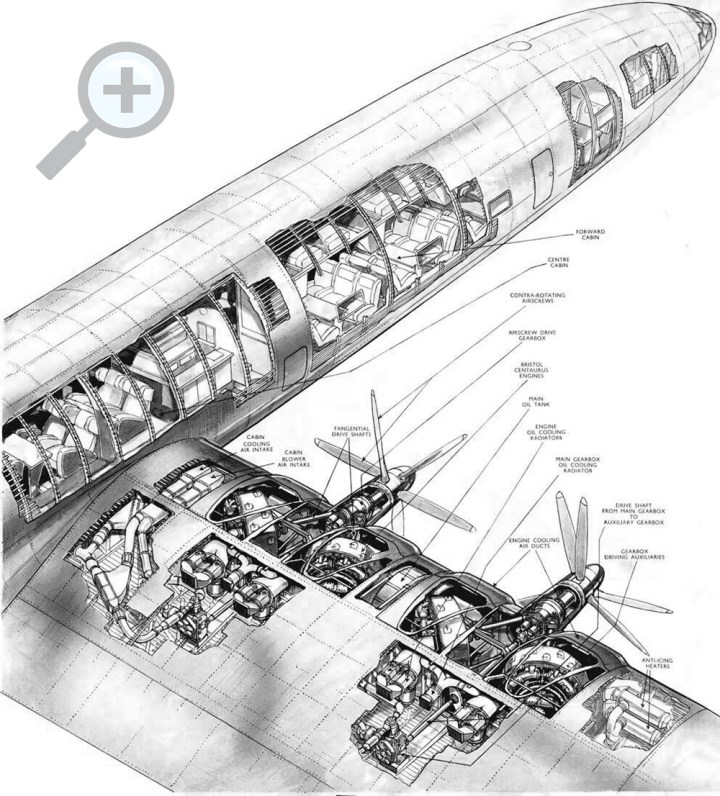

1949 Bristol Brabazon

Something interesting happened to cutaway art as the technological leaps of World War II made their way into civilian airliners and created a need to promote them to the travelling public. Suddenly, it was deemed wise to give these innovations the same kind of publicity as the creature comforts in the cabin.

One of the earliest examples arrives with the incredible Bristol Brabazon – the ‘large transatlantic landplane’ called for by the Brabazon Committee’s 1943 report on Britain’s future civil aviation needs.

The Brabazon airliner was innovative and anachronistic in equal measure, but it was big all over.

Imagine a Convair B-36 Peacemaker with seats. Both aircraft had the same wingspan of 230 feet (70 m) although the Brabazon was longer, at 177 feet (54 m) to the Peacemaker’s 162 ft 1 in (49.4 m).

If you’re looking for a modern yardstick, the Boeing 767-300 family has a similar fuselage length (180 ft 3 in, 54.94 m) but that wingspan is closer to the new Boeing 777X family’s 235 ft 5 in (71.75 m).

But while those modern airliners cram hundreds of passengers aboard, the Brabazon harked back to pre-war concepts of transatlantic luxury, accommodating just 100 passengers spread across seven cabin sections, a lounge area with room for 38 and a cinema with 23 aft-facing seats. (Yes, cinema!)

Equally innovative but redundant, and the feature chosen to impress the masses, was the extraordinary propulsion system. It comprised eight Bristol Centaurus 18-cylinder radial engines buried in the leading edge of the wing and generating 2,650 hp (1,980 kW) each. That’s 21,200 thundering horses in all.

More incredibly, the engines were mounted at an angle and connected in pairs to shared gearboxes that drove massive contra-rotating propellers. It was a remarkable symphony of power and engineering that could only be surpassed by one thing… the jet turbine.

And so the Brabazon was inevitably over-complicated, under-powered and outclassed by just about any other form of transport in terms of cost per available seat mile. Only two prototypes were ever built, and only the first of those was completed to a point where it was flown. It would accumulate a total of 382 hours of test and demonstration flights without attracting a single airline order. Not even from BOAC, which had helped develop the specifications.

Both Brabazons were broken up in October 1953. And both are still among the largest airliners ever built.

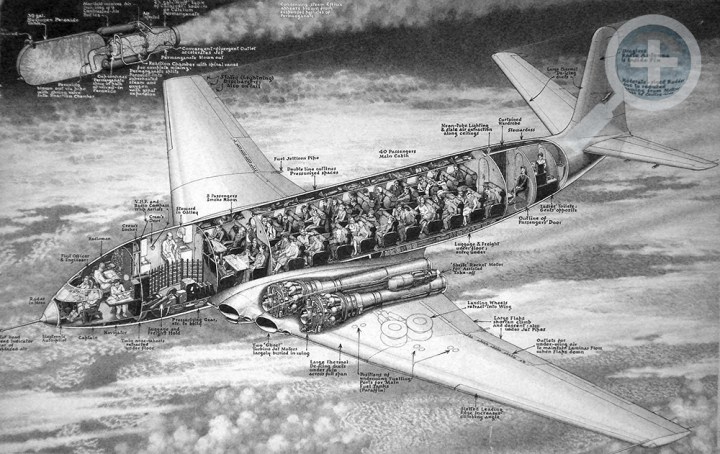

1950 DH 103 Comet (prototype)

Of all the airliner stories in history, the De Havilland Comet’s is easily the most tragic – in engineering terms, if not lives lost.

The British not only built the world’s first jet airliner but – and I think this is important – they also conceived jet airliners years before anybody else.

Like the Bristol Brabazon, the DH 106 Comet was a result of the far-sighted Brazon Committee – which first met in December 1942 and, by February 1943, had formally imagined the production of a jet-powered pressurised mailplane.

Let’s not forget that the outcome of World War II was far from a certainty when these plans were being made. While we can identify critical turning points when we look back, that period was what Churchill only dared to call ‘perhaps the end of the beginning’.

What’s more, the very existence of jet aircraft was still a closely guarded secret by both sides.

I don’t think there’s any need to re-launder the full story of the Comets here. Despite scrupulous efforts to explore all the possible limitations and failings of their technological leaps, De Havilland were in over their heads.

Hindsight gives the enthusiastic optimism of these cutaways a spectral quality, like watching grainy footage of passengers waving from the Titanic. The illustrations weren’t just aimed at the travelling public either. They were published in national newspapers and the message was clear – British industry was back. It would be a sadly brief zenith.

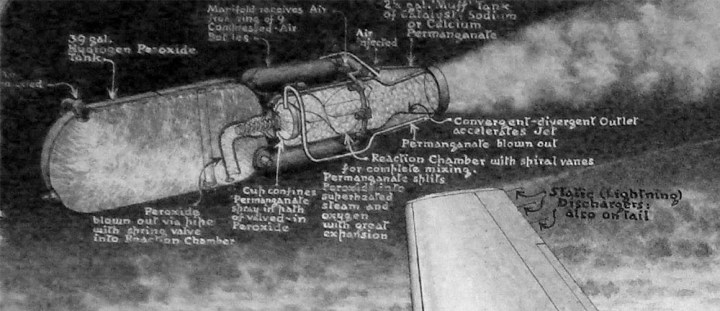

The unidentified Comet cutaway above is a pre-introduction image, highlighting the wonders of the cabin and those futuristic jet powerplants. The Halford H2 Ghost 50 engines were the Comet’s actual Achille’s heel. Producing just 5,050 lbf (22 kN) of thrust, they were barely adequate for the ambitious airliner design. That drove strenuous weight saving efforts which included desperately fine engineering margins on the skin panel thicknesses. Too fine, as experience would prove.

Note the prototype’s nose-mounted pitot tube in this illustration, despite the aircraft also having the four-wheel main gear bogey of production Comet Is.

Note also the ‘Sprite’ rocket motor between the two jet tailpipes, installed for added thrust during takeoff. The peroxide-and-permanganate rocket is detailed in the inset drawing at the top. This system was intended for hot and high departures, but was only tested some 30 times before being dispensed with. The four Ghosts were found to be adequate to lift the Comet’s all-up weight…

Comet I G-ALYP

This illustration dates from about two years later and shows Comet I ‘G-ALYP’. I suspect it is by the same illustrator and marks the anticipation of the Comets entering revenue service.

‘Yoke Peter’ (from Britain’s pre-NATO phonetic alphabet) was the first production model. She flew from Hatfield on 9 January 1951 and was then lent to BOAC for development flying.

As it happened, the aircraft also made the first fare-paying passenger flight by a jet airliner, still technically as part of BOAC’s proving program, but effectively inaugurating a regular jet service between London and Johannesburg, South Africa, on 2 May 1952.

Within two years, however, five of BOAC’s ten Comet’s had crashed – two due to handling errors and three due to structural failures. Spookily, three of those five hull losses occurred out of Rome’s Ciampino Airport.

Yoke Peter was the fourth. On 19 January 1954, just ten minutes into a flight from Ciampino to London Heathrow, the aircraft disintegrated and scattered into the Tyrrhenian Sea off the island of Elba. Four months later, G-ALYY would break up in remarkably similar circumstances and Great Britain’s Comet dream would be all but over.

The Royal Navy did a remarkable job of recovering wreckage from the ocean floor, and the Royal Aircraft Establishment completed a trailblazing forensic investigation into the accidents.

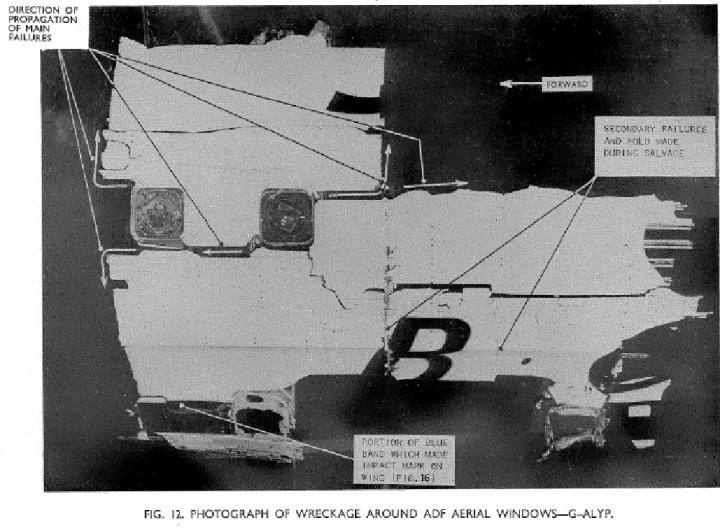

The full story can be explored much more comprehensively elsewhere. I would just continue the good work of putting to rest the misconception that the Comet accidents were due to square windows. They simply weren’t. Production Comet’s already had radiused window cutouts.

In fact, G-ALYP’s catastrophic skin failure was found to have propagated from a countersunk rivet hole near the corner of the ADF antenna cutout on the top of the aircraft, but not from the cutout itself. However, in a world addicted to quick and easy answers, I suspect the window corner story itself has propagated from the photos of that recovered fuselage section.

Ultimately, the Comet fleet’s fatal flaw was its weight minimisation, driven by the limited power of those early Ghost engines. The skins were made marginally too thin, instead of marginally too thick. It was also determined that the fuselage hoops weren’t heavy enough to arrest the tearing skin of both G-ALYP and G-ALYY once a fatigue failure had begun.

The Comet would be remade – larger, stronger and driven by more powerful Rolls-Royce Avon turbines. But it’s reputation was never recovered.

Concorde

Historically, Comet is the point where American manufacturers take the commercial jet industry and utterly dominate it until the 1980s.

Utterly…? Well, maybe not quite.

While it may not be the best of the best – more a great typical example – I still want to finish with the stunning Aerospatiale Concorde cutaway above… An all-but-impossible technical achievement, all-but-impossibly represented by Theo Page for The Daily Telegraph Magazine in 1972.

Long out of print, Concorde enthusiasts know that originals can still be found in auction houses and even on eBay from time to time. Good luck!

In the end, the engineering value of cutaway art became its raison d’être. Building on those early illustrations of key technical features, soon the whole structure of aircraft was being displayed on the page – beautifully, incredibly and in jaw-dropping detail.

By the 1970s, no self-respecting aviation publication would be without its cutaway artists and their regular contributions. Their names and artworks are easy enough to find online.

Just remember to be suitably dumbfounded by the mental and artistic ability required to imagine away the exteriors of these sophisticated machines, then lay bare the unfeasibly complex detail within.

That the basic design of the Comet was actually good was proven by the type progressing to the Nimrod which flew with the RAF until March 2010. The FE’s panel in the Concorde has to be seen to be believed, understanding that this was a (basically) MANUAL aircraft designed with slide rules flying 56 years ago being capable of supersonic cruise.

Now that “supercruise” is a reality, imagine designing Concorde today!

When i was a kid (50s-early 60s) I collected ALL of The Aeroplane cutaways. These and Airfix meant that I entered flight training in 1966 with a pretty good understanding of aircraft and how they worked.

Absolutely right. Based on batting average alone, it would be extremely unlikely for De Havillands to design a bad airframe! But the fact that the Nimrod fulfilled its maritime and ASW patrol role until 2010 says it all.

I’ll be sure to find some images of the Concorde FE station at some point in the near future. I know what you mean though – a full deck of switches and steam gauges for four complex Bristol Olympus installations has to be seen to be believed.

And finally, do you still have all those cutaways now??? They seemed to get more and more amazing as aircraft got more complex. I think it was actually Flight iNternational, but of of the two had a series o where they profiled their cutaway artists one by one. Worth finding if you can. I was so thrilled when Flight published their entire back catalogue online… and so gutted when they quietly took it back down again.

Sorry – no, but I had at least 50 or more. Flight International certainly provided many of them. I found a few here: Flight’s Aircraft Cutaway Archives | Technical Illustrators.org. This is interesting: EAGLE CUTAWAYS – AEROPLANES | Flickr

This is just an index but shows just how many were around: Cutaway drawing index

This has 59 illustrations: Category:Cutaway diagrams of aircraft – Wikimedia Commons

There are plenty more but most seem to have monetised them.

Bob

That’s a brilliant handful of links, thanks Bob. I didn’t know about the Cutaway drawing index – and that reminded me of Air International magazine. It was another of the great titles for cutaways.

Fantastic to see! I meant to leave a comment after the first installment of these cutaways, as it was such a great approach sharing these this way. A lot of work has gone into all of these images and into sharing them with us here. Truly great to see.

Thank you for all your ongoing efforts Mr Foxx.

Thanks Andrew. I feel like I barely scratched the surface, but it was still fun to see how far back they went and how beautifully rendered each one was. Anyway – glad you enjoyed them.

I’ve always been impressed by the cutaways and other artwork from this era. With the tools available today it’s not as impressive, but in the early-mid century era the documentation, right down to the construction plans themselves, were unparalleled works of art. They’re all worthy of framing and display.

I’m glad some of them have been saved. At the time they were created, I don’t think anyone had it in mind to permanently archive all this stuff for posterity. The industry was just moving forward at too rapid a pace to even think about looking backward. Or, I suppose one could say, looking far enough into the future to see a world where we would be doing that.

The root cause of the Comet structural failures was new information to me. I’ve seen documentaries and such about it, and they always pointed to the shape of the cabin windows as the issue.

–Ron

Hey Ron, good to hear from you. You know me… Always trying to find the bits of information that got lost. Now watch for some veteran aerospace engineer to chime in and tell us why I’ve got it wrong! 🙂

You’re absolutely right about the art value of those hand drawn blueprints and renderings. They really share a pedestal with my love of old maps – and if I could get my hands on some, man, would I.

I’m sure you know this story, but it illustrates (see what I did there) your point perfectly.

• https://vintageaviationnews.com/warbird-articles/the-man-who-saved-north-american-aviations-engineering-drawings.html

• https://www.aircorpsaviation.com/ken-jungeberg-collection/

• https://aircorpslibrary.com/blog/the-draftsmen-of-naa-inglewood/

Wow — sad to say, I did not know about the NAA engineering drawings. What a fascinating tale and long route they’ve traveled, from the draftsman’s tables at Inglewood to that storeroom to being flooded, recovered, dried out, stored again, and now living a second (third?) life for historians, rebuilders, maintainers, and avgeeks.

Since Air Corps is putting them online, it would be neat to get a few of them printed out, framed, and hung on the wall. That 10 foot long drawing of the B-25 rear gun assembly would be amazing hanging in a hallways somewhere.

When I’m in recurrent training in Long Beach, I’ll often pop over to a place called ‘The Hangar’ for a bite when we’re on a break. It’s located on what used to be the Douglas Aircraft delivery ramp. Anyway, it contains a bunch of small restaurants and is decorated with photos, signs, and imagery from the original Douglas plant. I love stuff like that. Not as much as I’d love seeing aircraft still designed and manufactured there, but it’s better than completely erasing the aviation history of the place, I suppose.

–Ron

Can you imagine?! I suppose a B-25 gun turret assembly bedspread could be a step too far (for some) but, yeah, as artwork in the appropriate setting it be just mind-bending. I guess because aviation is engineering, and business, and the progress over the past 120-some years has been inexorable, there’s been that mindset of “why would you celebrate obsolescence?”. But that’s a dangerous question. We forget history at our peril for a variety of reasons, and not just because we risk having to do it over. Equally, shredding or burning something that is inarguably beautiful is just plain wrong. Really, art defines humanity more than anything else and those NAA drawings are comprehensive proof of that.

I’d be willing to bet you could get one of those vellums recreated on a bedspread via the miracle of web-based shopping. I could see a whole line of merchandise: tablecloths, curtains, wrapping paper, paper towels, toilet paper (reserved for the less elegant designs, perhaps?)…

You’re so right about having to “do it over”. I’m thinking of the F-1 engines on the Saturn V, which Rockeydyne had to reverse engineer and dredge up from the bottom of the Atlantic Ocean in order to design the F-1B (which never went anywhere… but that’s another story).

–Ron

It wasn’t the physical printing I was worried about, so much as the final deployment. My wife let me have our wedding at an airport, but I think a gun turret bedspread might be a step too far… 🙂

Fair enough! 🙂