Under the skin

These days, 3D CAD and sophisticated rendering tools mean creating images that aren’t rooted in reality is a breeze. For most commercial applications, it’s the norm.

For example, I follow developments in electric aviation fairly actively, and the fact that last night’s beer coaster brainwave can be a fully rendered, photo-realistic artefact by lunchtime is clearly a real bonus for entrepreneurs, founders and getting funded. That said, it’s less of a help to those of us trying to discern what’s just over the horizon from what’s just behind a bull.

Back when commercial aviation was the technological wonder of the age, fledgling air transport operations had far fewer tools at their disposal. Instead, they turned to natural talent to share their vision with the fare-paying public.

Unsurprisingly, the results were genuine works of art – beautifully imagined and brilliantly executed…

1931 – Handley-Page H.P.45/42 G-AAXE Hengist

Hardly a period example, but a wonderful ‘exploded’ illustration nonetheless, this is a 1931 vintage Handley-Page H.P.45, built for Imperial Airways services between Britain and Europe.

The largest in-service airliner in the world at the time, the H.P.45 was a short-range variant of the H.P.42 four-engined sesquiplane airliner that Imperial operated on its long-range Empire routes – essentially to India and South Africa. The H.P.45 version carried more passengers at the cost of baggage, cargo and lucrative air mail capacity.

The top wing spanned 130 feet (39.62 m) and both wings were entirely metal framed with fabric covering. The design used streamlined Warren truss struts, which removed the need for bracing wires. The fuselage was 92 ft 2 in (28.09 m) long and skinned with corrugated aluminium to the aft bulkhead of the passenger cabin, then fabric covering back to the empennage.

Only eight H.P.42/45 airliners were built and most survived to be impressed into war service in 1939 – but all had been lost to accidents by the end of 1940. The type’s Wikipedia page details numerous media appearances, which would make for a fun YouTube rabbit hole to dive down.

Hengist, which first flew on 8 December 1931 (as Hespirides), was later converted to long-range H.P.42 configuration for services to India. It was lost in an airship hangar fire at Karachi, on 31 May 1937.

Out of interest, Hengist and his brother Horsa were legendary Germanic leaders who led the Angles, Saxons and Jutes in their occupation of post-Roman Britain. The Hespirides were three nymphs of twilight in Greek mythology.

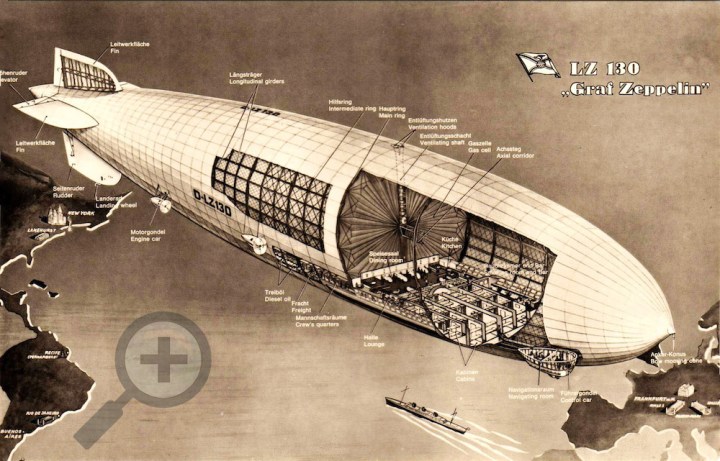

1938 D-LZ 130 ‘Graf Zeppelin II’

Something completely different… These views of the Graf Zepepelin II, sister ship to the ill-starred LZ-129 Hindenburg, are a great example of the flying ocean liner philosophy that dominated European airline thinking into the late 1940s – as we shall see.

Airships, like large flying boats, occupy a very short period where the technology of long range air travel had far outstripped the infrastructure. Both formats were fundamentally ways to provide an air service where runways were few and far between.

The massive construction effort that was part of World War II quickly put paid to both.

Despite LZ-129 and LZ-130 being nominally identical, LZ-130 was significantly improved by the time she was completed – with too many changes to detail here. Her tractor propellers, instead of Hindenburg’s pusher arrangement, are one easy tell.

However the Hindenburg disaster put paid to Graf Zeppelin’s commercial career before it even got off the ground, and her future was firmly driven six feet under by the United States’ refusal to supply helium as a lifting gas following Nazi Germany’s annexation of Austria.

Ultimately, Graf Zeppelin II only made a handful of ‘glory flights’ for Nazi propaganda and officials, before both she and the original Graf Zeppelin (LZ-127) were scrapped in April 1940.

Suffice to say, there were more advanced uses for their enormous aluminium skeletons.

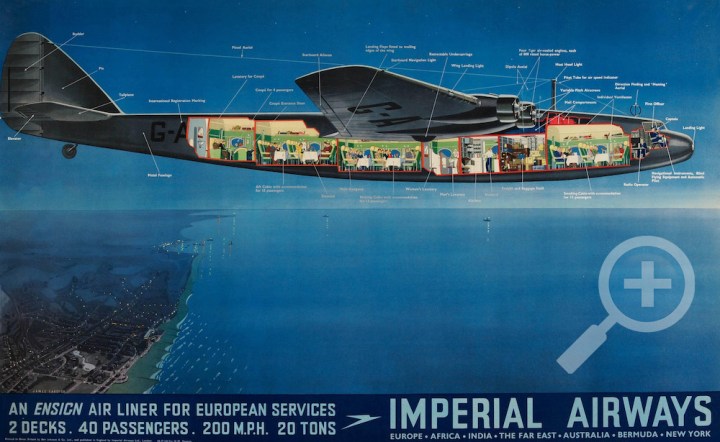

1938 – Armstrong Whitworth AW27 Ensign

Looking very much like a 1940s design – okay, a British 1940s design – 1934’s Armstrong Whitworth Ensigns were ordered to replace Imperial Airways’ ageing and dated H.P.42 biplane giants (see H.P.45 Hengist above) for international landplane services.

As such, they must have seemed like an enormous leap forward – as long as you didn’t look too closely across the Atlantic. Either way, the Ensign’s 160 knot (290 km/h) cruising speed was virtually twice that of the outmoded biplanes. And like the H.P.42s, these were the largest landplanes in the world when they entered service.

The initial order was placed alongside the requirement for long range seaplanes that would produce the Short Empire flying boats. More on those later. The final Ensign order totalled 14 airframes. Various delays, including thoughts of designing a smaller parasite aircraft to piggy-back aboard Ensigns, meant the first example didn’t fly until 1938.

The launch was a disaster. Three of five available Ensigns were dispatched from England to Australia carrying Christmas mail – and exactly none made it. Merry frickin’ Christmas! All suffered mechanical failures and one had to be flown 2,500 miles (4,000 km) home with its undercarriage down.

They were all returned to Armstrong Whitworth for substantial modifications and were re-delivered in June 1939 – just in time to be placed into storage, then camouflaged and handed to BOAC for (civilian) war work. Three aircraft were lost during the fall of France, while a fourth was bombed at Bristol, England. Another force landed in North Africa during 1942, was repaired and operated by the Vichy French, then seized by the Germans – and promptly deemed obsolete.

The remaining seven aircraft continued in service throughout the war and the last examples were scrapped in 1947.

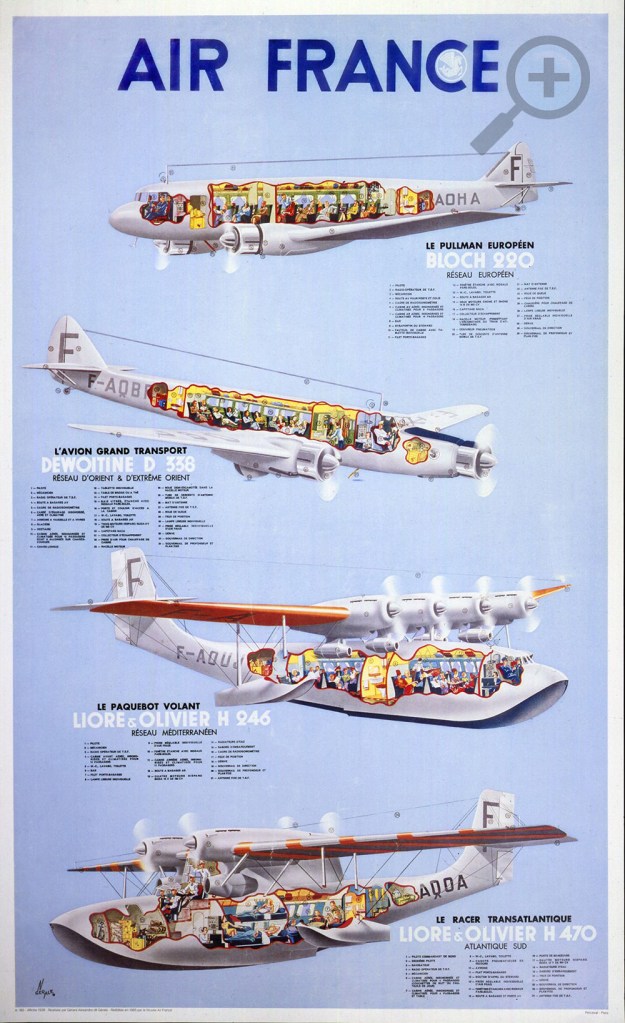

1938 Air France Poster

Air France has existed as a national flag carrier since 1933, but its component companies date back to the world’s first fixed wing scheduled passenger service – operated within France by the Compagnie Générale Transaérienne (CGT) in 1913. While most of us see the DC-3 when we close our eyes and imagine 1930s air transport, the French carrier loyally supported its own country’s aircraft industry (and arguably still does).

Thus, this quartet of rare and naturalement stylish French airliners from the pre-war period.

Block MB 220

While looking a little like a DC-2 in the cutaway view, the Bloch MB 220 had a much squarer fuselage, clipped wings and capacity for 16 passengers plus four crew compared to the DC-2’s 14 pax. Just 17 were built from 1936, with only six surviving the war and soldiering on with Air France until 1950.

Dewoitine D.338

The Dewoitine D.338 was a 22-passenger main-route airliner that first flew in 1935. Similarities to the A.W.27 above are probably just form following function – but interesting nonetheless. Designed to serve France’s global connections, the airliner had a maximum range of 2,000 km (1,100 nm) but capacity was reduced to 18 passengers for services within South America, 15 for flights to North Africa, and just 12 for flights to the Far East. Interestingly, its 650 hp (480 kW) Hispano-Suiza 9V16/17 engines were license-built versions of the ubiquitous Wright R-1820 Cyclone.

Lioré & Olivier Le0 H.470

The Lioré & Olivier aircraft company was founded way back in 1912 and was nationalised in 1936, as a conglomeration with the Bleriot and Bloch companies. The result, SNCASO, was eventually rolled into Sud Aviation then Aerospatiale and, ultimately, Airbus.

Lioré & Olivier built up an impressive resumé of flying boat designs over its history. By the late 1930s, the company was building craft as elegant as any in the world.

The LeO H.470 (‘The Transatlantic Racer’) was actually the older of the two shown here, first flying in July 1936. It was powered by four 860 hp (650 kW) Hispano-Suiza 12Y motors mounted in push-pull pairs within two perfectly streamlined nacelles. They could carry up to 12 passengers but were usually set up for four to eight, had a top speed of 196 knots (360 km/h, 225 mph) and a range of 3,200 km (2,000 miles). They ended their days serving in Senegal under the Vichy French, and were scrapped in 1941 after spare parts ran out.

Lioré and Olivier Le0 H.246

The H.246 (‘The Flying Ocean Liner’) first flew in September 1937 and entered service on trans-Mediterranean routes in October 1939. Not a great time. The third aircraft was taken over by the military and completed as a bomber with a glazed nose and under-wing bomb racks. When Germany occupied Vichy France they seized this aircraft and three Air France machines as troop transport and evacuation aircraft.

Two other H.246s that sat out the war in Algiers were briefly returned to Air France service post-war, but only operated into 1946. As an airliner, they had capacity for up to 26 passengers and five crew, with a top speed of 180 knots (330 km/h, 210 mph) and a 2,000 km (1,200 m) range.

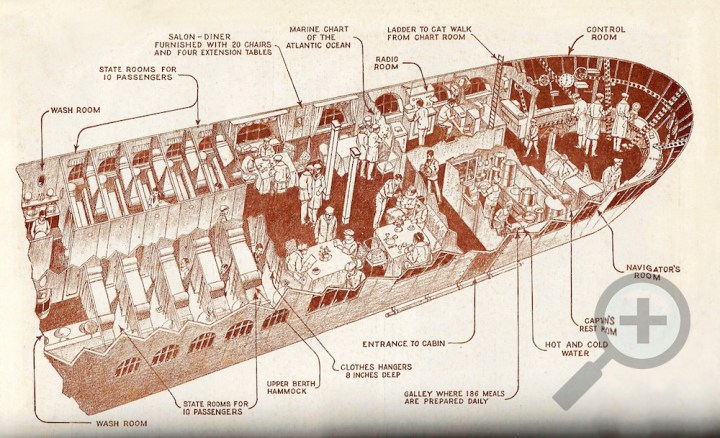

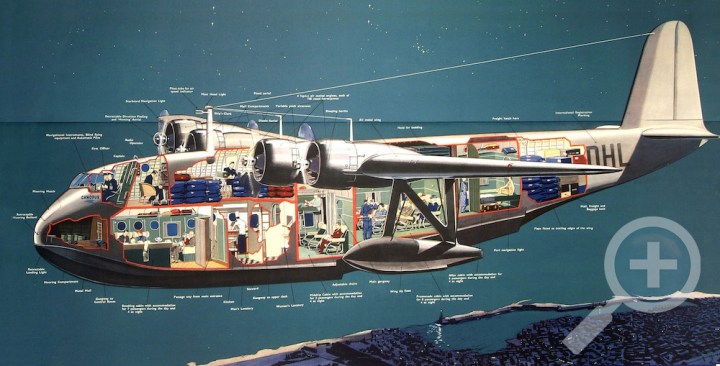

1937 Short Empire S-23 Canopus G-ADHL

The Short S.23 ‘Empire’ or C Class flying boats were designed to connect Britain’s furthest points of Empire and the mother country with rapid (for the time) passenger and – more importantly – air mail services.

Incredibly, despite routes stretching half-way round the world from the UK, to points like Cape Town, Sydney and Auckland, the design specification only required a range of 700 statute miles (1,100 km) and a special capability of 2,000 miles (3,200 km) for Atlantic crossings. Compare that to Being’s 314 Clippers designed for Pan American, which entered service a few years later with a range of 3,685 mi (5,930 km) and several times the carrying capacity.

Still, Britain’s was a maritime empire with harbours and coaling ports spread strategically along every major trading route, and the Empires did sterling service by using the same outposts.

G-ADHL Canopus was the first of the type, and this cutaway was no doubt created to promote the launch of revenue services from February 1937. It’s a source of continual amazement that Imperial Airways was so desperate to launch their large flying boat service that they forbade Shorts from building a prototype and ordered 28 machines before the design had even been buttoned down.

What’s even more incredible is that this rush was driven by Imperial’s urgent need to replace its fleet of obsolete Short S.17 ‘Kent’ flying boats, which looked like floating H.P.42 airliners (see above) and were of the same early-1930s vintage.

By contrast, the Empire boats were positively modern, being cantilevered monoplanes with all-metal, flush riveted skins, advanced wing flaps and Bristol Perseus XIIc sleeve-valve radial engines.

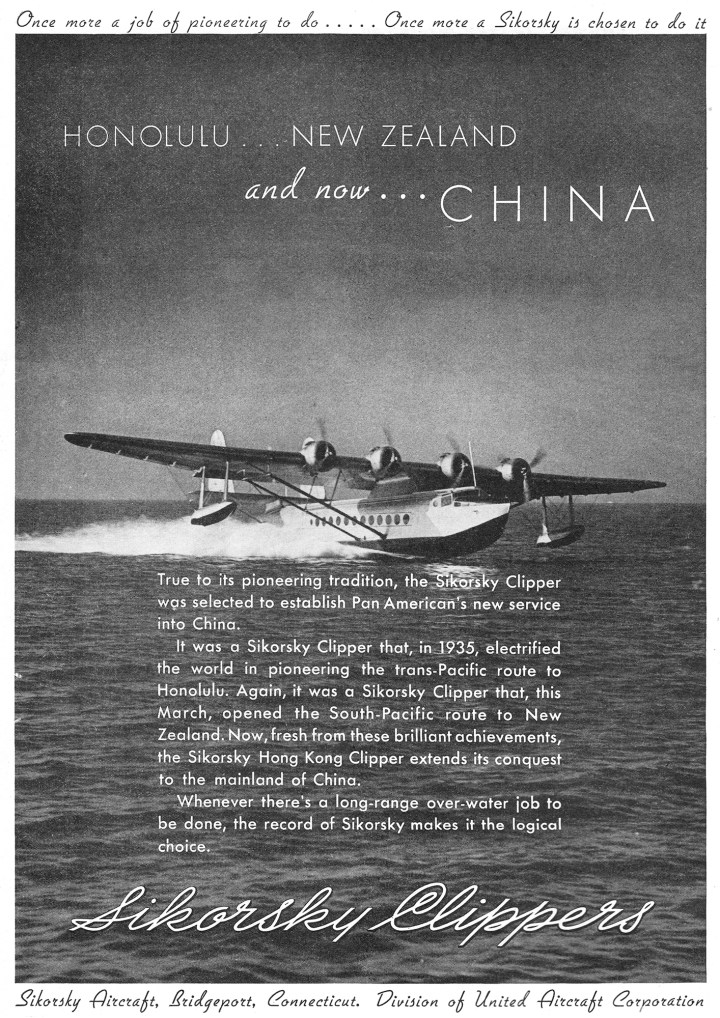

That said, their direct American comparison would be the Sikorsky S.42 Clipper which was designed to a 1931 brief and first flew in March 1934 – offering a 1,200 miles (1,900 km) normal range and 3,000 mile (4,800 km) ferry range. No wonder Imperial Airways was in a hurry!

In the finest British tradition, lack of range turned out to an issue from the get-go. The S.23s were part of some fascinating experiments to make them true transatlantic craft – including aerial refuelling west of Ireland and again east of Gander, using a pair of converted Handley Page H.P.54 ‘Harrow’ bombers. It was a first and last for large airliners.

The S.23 was also the basis for the S.21 carrier flying boat and it’s piggy-back S.20 ‘Mercury’ parasite seaplane, which was intended to launch mid-route and fly ahead with urgent mail. This Short-Mayo Composite was tested very successfully in the late 1930s, but the experiments (and the need for them) were cut off by hostilities in 1939.

The venerable Canopus flew with BOAC throughout the war and was broken up at Hythe, on Southampton Water, in October 1946 – exactly ten years after she’d been delivered new.

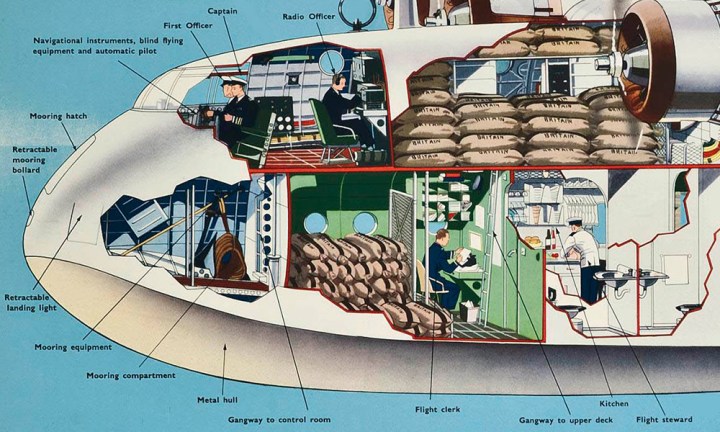

1937 Short Empire S.23 Calypso G-AEUA

Having been delivered new to Imperial Airways in August 1937 and used for flights to Karachi, Calypso was assigned the inaugural Southampton, England to Sydney, Australia service in July 1938. In 1939, she was transferred to QANTAS (Imperial and QANTAS effectively shared the vital England-Australia air connection) – and I suspect this cutaway image was used to publicise the new service to Australians.

The artwork appears to be based on a very similar template to the one above, but you’ll notice the QANTAS aircraft has some differences to her internal layout. The smoking lounge on Canopus has been replaced by mail bags and the flight clerk’s position, while the top deck mail room is now entirely filled with bags. That implies more mail was to have been carried on the Australia flights.

Regardless, it was not to be. At the outbreak of World War II, the newly arrived aircraft was impressed into the Royal Australian Air Force and became A18-11. She was involved in a number of daring long-distance rescues during the dark early days of the Pacific war, snatching RAAF personnel and civilians from under the noses of the advancing Japanese.

On 8 August 1942 she left Port Moresby, Papua New Guinea, to rescue survivors from a small cargo ship that had been sunk in the Gulf of Papua. As she came in to land on the heavy seas, a series of large waves stove in her nose, breached the fuselage and then tore the skin apart. Calypso sank within two minutes. Leading Aircraftman George Edwards was lost in the accident. The surviving crew (and one survivor from the shipwreck) spent the next 10 days paddling in their life rafts to land and trekking to an Australian spotting station at Kikori, PNG.

Re the LeO H470, the image you used is a MIL a/c – note the French roundel. From another website: At the outbreak of hostilities, the Navy commandeers the 5 machines that are modified in Saint-Raphael for their new mission of distant reconnaissance. The fuselage is extended in its front part to receive the glazed position of the observer / navigator. It receives a defensive armament: 4 machine guns of 7.5mm and offensive with 4 lances bombs for a maximum of 600kgs of bombs. The civil versions did not have this nose.

Thanks Bob!