Click here for previous chapters

When the bomber turned I started wondering if the drop was being canceled. Should I re-install the control locks? The uncertainty made me irritable.

“If you’re gonna drop me,” I thought, “drop me. If we’re gonna return and land then let’s go land.”

Inadequate training

Only later did I learn that there’d been no problems or abnormalities that caused the bomber to circle around for another run. I only imagined it due to the immense stress I was under and due to a lack of confidence from inadequate training.

Also, I was probably suffering from what we called ‘pilot’s confusion’ the inability to think clearly after a long period at high altitude due to oxygen deprivation.

What I didn’t realise was that we were in fact very close to the release point. Yet I was still thinking the drop would probably be cancelled. I still hadn’t made out any visible landmarks and was beginning to relax.

Finally, I caught a glance of the Toné River. I was just pressing my face against the canopy to look for our second airfield when it happened.

My blood ran cold

Like the sound of bamboo bursting in a fire there was a loud bang overhead. I suddenly felt weightless. My body jerked to one side and the top of my head slammed against the canopy.

“They dropped me!” I thought in disbelief.

Even though the seat belt was tight I floated off the seat. The belt bit into my thighs. In an instant I was almost standing in the cockpit. They’d released me without warning, before I was mentally prepared. Further dazed from the blow to my head, I was totally confused.

I quickly grabbed hold of the control stick. But because I was still floating in negative G, when I tried pushing it forward I could barely move it.

Freed from the bomber the K-1 tipped to one side and began falling earthward in a steep arc. I panicked. No! Gotta do something! I’m gonna stall, crash and die. I felt my heart constrict and my blood ran cold.

Dive! Get the nose down! Get it flying, was all I could think.

I needed airspeed. It felt like I was being sucked to the bottom of a transparent sea, and the earth was the sea bottom.

The nose must be too high

When I was first released from the bomber the surface of the earth appeared infinitely far away.

From that altitude, even after falling some distance the scene hardly changed, as if I wasn’t even moving.

But when the bomber dropped me I definitely felt myself falling. Even today I can clearly recall that strange sinking feeling as my butt floated off the seat. It was a bit like the sensation I experienced just as my seaplane left ground effect before alighting on the water. So I assumed that the nose of the K-1 must be too high. Otherwise it wouldn’t feel that way.

Thinking I was losing airspeed I became badly scared.

However, it was merely an illusion. Looking out over the nose I saw that the upper surface of the nose was level with the horizon. That meant I was flying level. But I couldn’t believe it.

Those ten seconds felty like an eternity

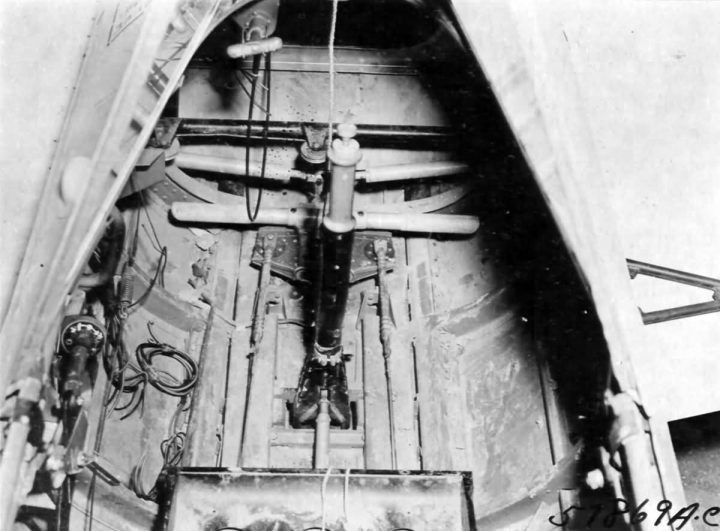

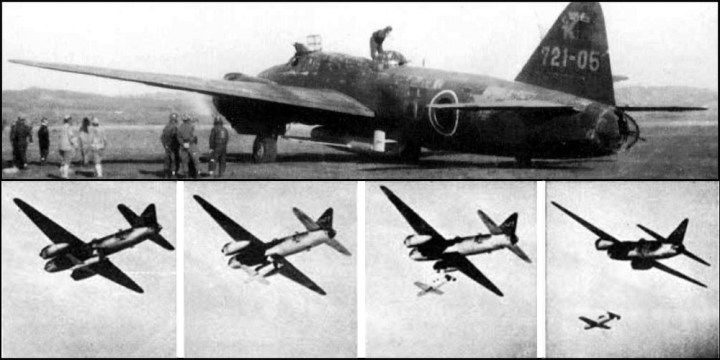

What was happening was this: After release the unpowered K-1 would at first fall in a horizontal attitude for about ten seconds. Then, as it lost speed, the weight of the ballast in its nose would cause it to slowly pitch downward and it would start gliding and flying on its own. So the pilot had to wait for this to take place.

But those ten seconds felt like an eternity! All I could think of was Lt. Tsutomu Kariya who had stalled his K-1, falling to his death.

I was so terrified of stalling that I dove too steeply.

Thinking back on it now, the attitude I was flying at was fine and there was no need to panic.

But during training we’d had two admonitions about the K-1’s flying characteristics that I couldn’t get out of my head: ‘Recovering this aircraft from a stall is impossible.’ and ‘Don’t stall it. If you do, you can’t recover because there’s no propulsion.’

In any case, as the uncomfortable floating sensation diminished I relaxed, only to realise that I was diving too fast.

Spinning like crazy

I glanced quickly at the airspeed indicator. It indicated 250 knots. The proper airspeed during descents was 170 knots. I was diving too steeply and losing altitude fast, a fact clearly indicated by the rapidly unwinding altimeter.

The altimeter had two pointers. One indicated 100-metre units, the other 10-metre units. The 10-metre pointer was going spinning like crazy.

Even before looking at the altimeter I was worried about how much altitude I was losing but now, seeing that needle spinning around like a propeller I started to panic.

I had to slow down and stop losing so much altitude. And because I still hadn’t recognised any landmarks or found the field, I had to figure out where I was and set up my approach.

This had to be flown at a set airspeed, over a predetermined point and from a certain altitude. Any deviation from those critical parameters would end in disaster because a glider has only one chance to land.

A bucking bronco

I raised the nose slightly to kill off some airspeed. But in my panic I must’ve pulled back too hard on the stick because the nose shot up too quickly, and the K-1 started to porpoise.

The nose rose high above the horizon and the sudden G force pinned me to the seat. I couldn’t move.

I was like a cowboy riding a bucking bronco. I couldn’t get it under control.

NEXT TIME: A once-in-a-lifetime jump >

These extracts are from the diary of Masa’aki Saeki, trainee Yokosuka MXY-7/K-1 Ohka pilot, 721st Kōkūtai Jinrai Butai, Imperial Japanese Navy.

Translated by Nicholas Voge and shared with permission.

Nicholas Voge is a retired Pt. 135 airline pilot who spent his younger years living in Japan where he worked as a translator, copywriter and riding model for the Japanese motorcycle manufacturers. His translations include The Miraculous Torpedo Squadron, The Inn of the Divine Wind and Kaiten Special Attack Group, A Story of Stolen Youth.