Click here for previous chapters

Around mid-December there was a rumour that our groups would be reorganised, and it seemed like we would soon be departing for the Philippines.

We heard that the Ohkas had already been shipped to Clark Field and that they also planned to send them to Sumatra, Taiwan, Okinawa, Vietnam and Singapore. Once the Ohkas were in place, they would merely have to fly the bombers to the location to be ready to launch attacks.

Be prepared to depart at any moment

One evening all the aircrew were suddenly ordered to attend a group meeting at the bomber pilots’ mess hall.

New groups were formed. I was in Group 4. Each formation in a group consisted of three Ohkas. The lead pilot in my formation was Lt. Tsuneo Hiyoshi, No. 2 was Flight Seaman Keisuke Isogai and I was No. 3.

At the end of the meeting the following announcement was made:

“Group 1 will remain at Kōnoiké to instruct new arrivals. Everyone else, be prepared to depart at any moment. The date and time of departure has not yet been decided. If ordered to depart tomorrow, you will. Those who haven’t yet flown the K-1, do so immediately!”

This fat, short one is a battleship

In the days that followed, when we had no flight duties, we got our personal effects in order or studied.

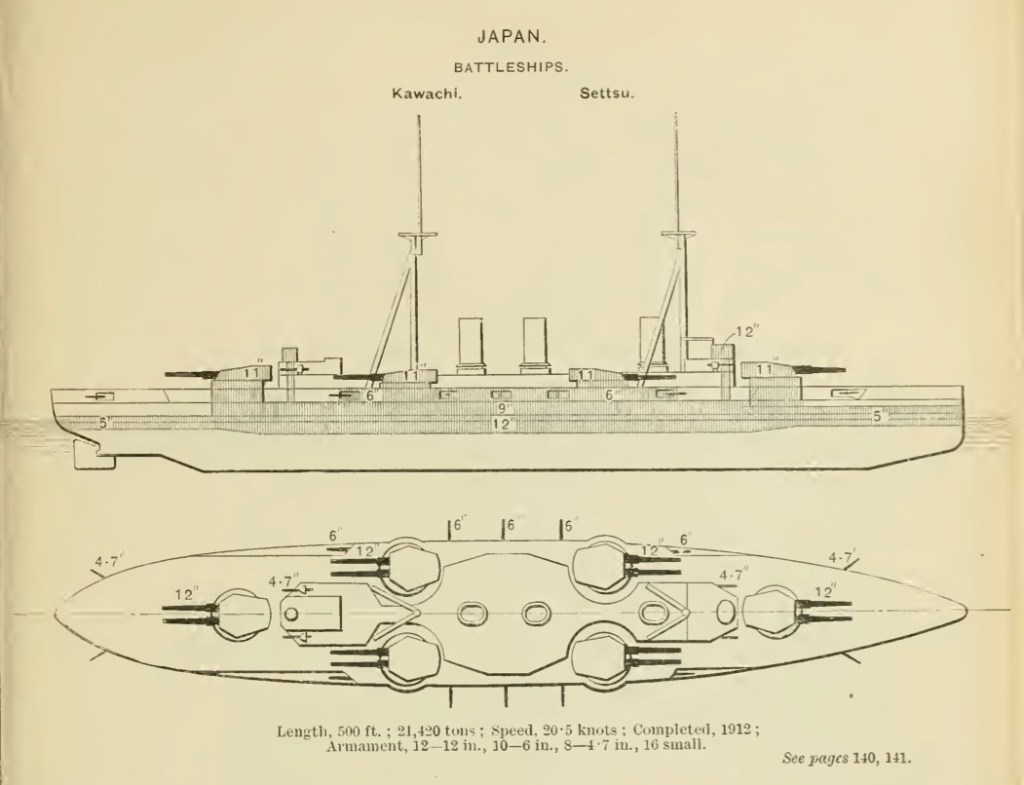

Our textbooks were ‘red books’, meaning top secret. Our studies included such topics as judging a ship’s speed by the length of its wake and identifying warship types, all of which was explained to us by a torpedo-bomber officer. He would show us the silhouette of a warship and say, for example, “This fat, short one is a battleship.”

None of this was new to me because I’d been reading magazines like ‘Navy Graphic’ since I was a child.

Body slamming attack

In one of the lessons they placed models of American warships on the sand to explain the various battle formations such as perimeter formations, single-file formations, simultaneous turns, etc. We looked down at these formations from various vantage points so as to be able to recognise them from the air.

We were also shown an interesting training film shot at the Kuré military harbour.

It showed a pilot’s eye view during a mock taiatari (body slamming) attack. The film froze at intervals to give us a good look at the shape of the target ship’s bridge and superstructure, while captions showed the attacking aircraft’s altitude during each freeze frame.

As the film continued, the target grew in size and the approach speed increased until last moment when the recording aircraft broke off.

However, in spite of the frenetic preparations, our mother-ships, the bombers, were still not ready to deploy. Many didn’t yet have their defensive armament, or their engines leaked oil during test flights. In fact, there were so many maintenance issues that flying them to the Philippines was simply out of the question.

Kyūshū for combined training

This problem soon became moot, because during this period the enemy had accelerated their counter-offensive, secured Leyte and moved on to Mindanao Island.

Our deployment to the front was consequently pushed back to January 10, but even that date seemed doubtful and nobody really believed it.

As 1944 came to an end and with January of ’45 rapidly approaching, our squadron deployed to Oita in Kyūshū for combined training. We separated into two groups, one of which went by air, the other by train. I went by train.

When we stepped of the train at Oita with our duffel bags, on which gōchin (Thunder) was written in large characters, a waiting truck took us to Oita Airbase.

Oita was a fighter base and as such there were many new aircraft I’d never seen before. These included the Saiun, Gekkō, Ginga and Tenzan.

There was also a unusual twin-engine plane with a long, slim fuselage and a glazed lower nose section made with pieces of angled glass that looked like a German Dornier. I was told it was used for submarine hunting. There was also a Suisei (Yokosuka D4Y) on the field.

The engine would roar into life

During the week I was there I spent every day training over the Bungo Strait. We’d awaken in the pre-dawn darkness to start the engines and warm them up.

“Switch OFF,” the ground crew would yell.

“Switch OFF,” we’d reply, followed by, “Engage inertial starter!”

Priming the engine, it would make some clicking sounds and I’d hear gasoline dripping.

“Contact!” I’d yell, engaging the inertial starter.

The engine would cough a few times, I’d give it some more gas with the hand pump, the plane would shudder and the engine would roar into life. Then I’d push the throttle forward, watch the manifold pressure gauge until the needle reached the red zone then retard the throttle.

While we flew around in the Zeros the bomber crews were busy practicing radio communication, navigation and torpedo runs over the ocean. The fighter pilots were also training constantly.

Tenzan

One day, during a break, one of my former classmates came over, tapped me on the shoulder and said, “Oi, how’s it going?”

“Oh, Omae, what’re you doing here?”

“I’m in the testing unit at Yokosuka. You with the special attackers?”

“Yeah. What’re you flying, dive bombers?”

“No, the Tenzan. Isn’t the instructor Fujishiro with you guys? He taught me how to fly. He’s a good guy.”

After chatting a bit we parted and shortly after I saw him take off in his incredibly long-legged Tenzan and disappear into the distance.

Camouflage isn’t gonna do much good

Our first flights of the day were made during the early morning. We lined our Zeros up on the runway, and one by one, with a wave of the hand followed by a cloud of dust, took off at intervals until all three of us were in the air.

Immediately after lift off we’d take our right hands off the stick to crank up the gear and fly the plane with our left.

In no time our formation was out over the ocean.

The sea is beautiful when seen from above on a sunny day. But as a seaplane pilot I couldn’t help noticing that a big swell was running.

From time to time, Lead would look over at us to check that we were still with him. Before long we were quite a ways offshore. The fleet that was to be our practice target should be steaming along in the offing at Sadamisaki.

I scanned the sea surface intently. Suddenly I saw them. Against a canvas of dark blue the ships looked like matchsticks lying on their sides and were brightly illuminated by the sunlight.

If they’re gonna reflect light like that, I thought, camouflage isn’t gonna do much good. Nothing seemed to work against natural light and shadows. Once again it occurred to me that no matter what they tried, ships at sea were easy to spot.

The next moment I realised that was just the scene I’d be looking at during an actual attack.

The signal to line up and attack

We made a series of leisurely turns over the ocean at 2,000 meters (about 6,500 feet).

Our first target was the lead ship, the old battleship Settsu. The second ship in line was the carrier Hōshō. I didn’t know the name of the third. The last ship was a tanker.

They were to our right as we approached them from the rear. We flew along parallel to them until we were a just ahead of the carrier.

At that point the lead plane waggled its wings, the signal for us to line up and attack individually. We got into an echelon formation and the lead plane did a wingover and started on its attack run. I watched his plane accelerate and grow smaller as it plummeted downwards, finally fading into invisibility against the dark sea.

Number two followed, soon disappearing from sight.

Then it was my turn. I could choose whatever ship I wanted, so of course I chose the carrier. With one eye on the altimeter and the other on the ship I plunged from the sky with such velocity that it seemed like the sea and ship were rising up to meet me.

A fleeting glance of the carrier’s huge deck

I felt myself gripping the stick with all my strength. The carrier was plowing along at 12 knots, throwing up sheets of spray from its bow as it punched through the waves, leaving behind a foamy wake.

I pressed home my run with determination. In a matter of seconds the deck filled my windscreen. This was the instant at which I would take the fatal plunge. The crew in their white work clothes were clearly visible on deck. They glanced up at me casually but didn’t appear the least bit concerned, no doubt used to being targets.

A split second from disaster I expelled all the air from my lungs and pulled back hard on the stick. The G force compressed me onto the seat. On the verge of losing consciousness I caught a fleeting glance of the carrier’s huge deck sweeping past close beneath me. An instant later I was soaring skyward on the inertia of my dive with the carrier growing ever smaller behind me. By the time the three of us reformed the ships were mere specs upon the vastness of the sea.

“Once you start your attack don’t turn and break it off above the target because you might collide with the plane coming down behind you,” we’d been told. I recalled this admonition with a shock, because as I reviewed my attack the next flight of Zeros was rapidly approaching to begin their own mock attacks.

Before we had time to catch our breath our week at Oita passed and we were back at Kōnoiké.

NEXT TIME: One man can kill a thousand >

These extracts are from the diary of Masa’aki Saeki, trainee Yokosuka MXY-7/K-1 Ohka pilot, 721st Kōkūtai Jinrai Butai, Imperial Japanese Navy.

Translated by Nicholas Voge and shared with permission.

Nicholas Voge is a retired Pt. 135 airline pilot who spent his younger years living in Japan where he worked as a translator, copywriter and riding model for the Japanese motorcycle manufacturers. His translations include The Miraculous Torpedo Squadron, The Inn of the Divine Wind and Kaiten Special Attack Group, A Story of Stolen Youth.