Andreas Feininger

. . . a sequel to the previous article, Works of Art

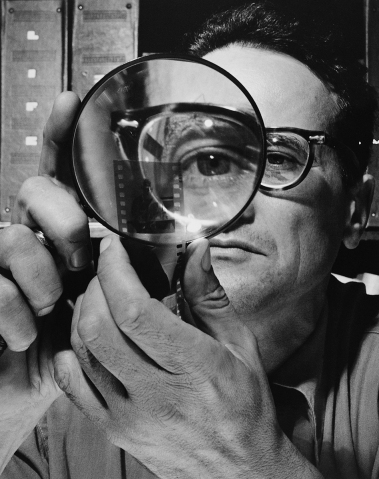

Another of Alfred T Palmer’s superb staff photographers at the United States Office of War Information (OWI) was a young freelancer with a very bright future – Andreas Feininger (1906 – 1999).

Over his lifetime, Feininger created an enormous portfolio of famous images, including many iconic photos of New York City in the 1950s and 60s, and penned a small library of books on photographic technique.

A consummate lensman

Of German-American descent, Feininger was born in Paris and trained as an architect in Germany. He moved to Sweden in 1396 and began to concentrate on photography.

Thanks to his father’s US citizenship, he was able to migrate to the USA as a freelance photographer in 1939, shortly before the war in Europe, and was recruited by Palmer and the OWI.

After a year criss-crossing America to document the war effort, he joined the staff of Life in 1943 and completed almost 350 assignments for the magazine before leaving in 1962.

Already a consummate lensman by 1942, Feininger was also a master of perspective and pattern – no doubt the fruit of his architect’s eye and its Bauhaus schooling. So when the OWI sent him to record the plants of Pratt & Whitney, Hamilton-Standard and Boeing, the result was always going to be a striking reflection of mass production’s incredible capacity and capabilities.

The value of aesthetics

Of course, this gallery could only be the slightest sampling of Feininger’s OWI portfolio, let alone his life’s work, the entire OWI monochrome archive or just America’s wartime aircraft industry.

But I like it most because even in the intense crisis that the US felt through 1942, the inherent value of aesthetics and artistry was allowed, even encouraged, to prevail.

And I think that should be the rule, not the exception.

As always, click the images to open larger versions.

“What matters is not what you photograph, but why and how you photograph it. Even the most controversial subject, if depicted by a sensitive photographer with honesty, sympathy, and understanding, can be transformed into an emotionally rewarding experience.”

– Andreas Feininger

1. Rows and rows of propeller blades line Hamilton-Standard’s Hartford, Connecticut factory, bearing their individual production order and inspection slips. This trip to H-S and nearby Pratt & Whitney was almost certainly Feininger’s first assignment for the newly formed OWI, when he visited in June 1942.

Andreas Feininger, June 1942. (LoC P&P, LC-USE6-D-008099)

2. Three-bladed propeller assemblies stand racked and ready for shipment from Hamilton-Standard. Charles Lindbergh crossed the Atlantic behind a Standard propeller in 1927 and the company had developed the hydraulic constant-speed propeller in the 1930s. It was already the world’s largest propeller maker by 1939 and production soared further to meet war demands.

Andreas Feininger, June 1942. (LoC P&P, LC-USE6-D-008096)

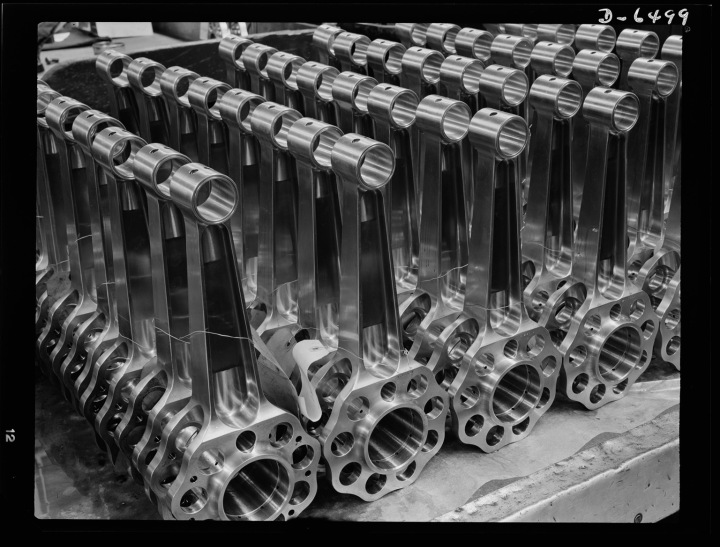

3. When Feininger arrived at the Pratt & Whitney engine plant in East Hartford, Connecticut, he discovered a symphony of polished steel and repeating patterns. Here, his OWI brief to educate Americans about the war effort took second place to photographic appeal, and he captured these finished master rods for radial engines in all their sculptural, technical and muscular beauty.

Andreas Feininger, June 1942. (LoC P&P, LC-USE6-D-006499)

4. In another eye-catching pattern, a Pratt & Whitney worker stacks the finished front halves of crank cases for single-row radial engines – creating alien-looking columns until the parts are needed for assembly of the motors and a part in the war effort.

Andreas Feininger, June 1942. (LoC P&P, LC-USE6-D-006501)

5. True works of industrial art, these gleaming crankshaft assemblies receive their final inspection before being moved up the line for installation. There are no clues in the image, but they’re most likely cranks for Pratt & Whitney’s two-row, 14-cylinder, R-1840 Twin Wasp. One of the most widely used radials of the war, the Twin Wasp displaced 1,830 cubic inches (30.0 litres) and powered everything fromAustralian-built Beauforts, Boomerangs and Woomeras, to B-24s, C-47s, Short Sunderlands, Vickers Wellingtons and more. In all, nearly 174,000 (!) were built.

Andreas Feininger, June 1942. (LoC P&P, LC-USE6-D-006516)

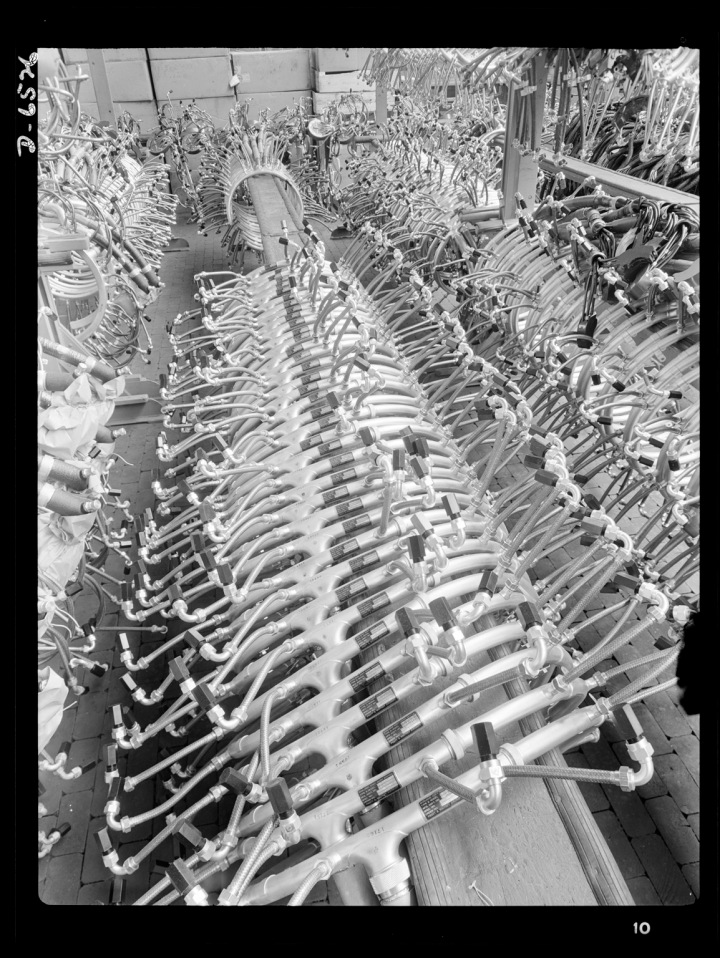

6. Pre-made ignition harnesses stretch into the distance (and up toward the roof) in part of Pratt & Whitney’s engine factory. These particular units are for single-row R-1340 Wasps, and will most likely power the ubiquitous North American T-6/Harvard family.

Andreas Feininger, June 1942. (LoC P&P, LC-USE6-D-006526)

7. Just as the aircraft manufacturers would test-fly all their finished aircraft, Pratt & Whitney tested every motor they produced on test stands like these. Feininger captured a striking symmetry in the test tunnel, given extra interest by asymmetric elements like the stairway.

Andreas Feininger, June 1942. (LoC P&P, LC-USE6-D-006534)

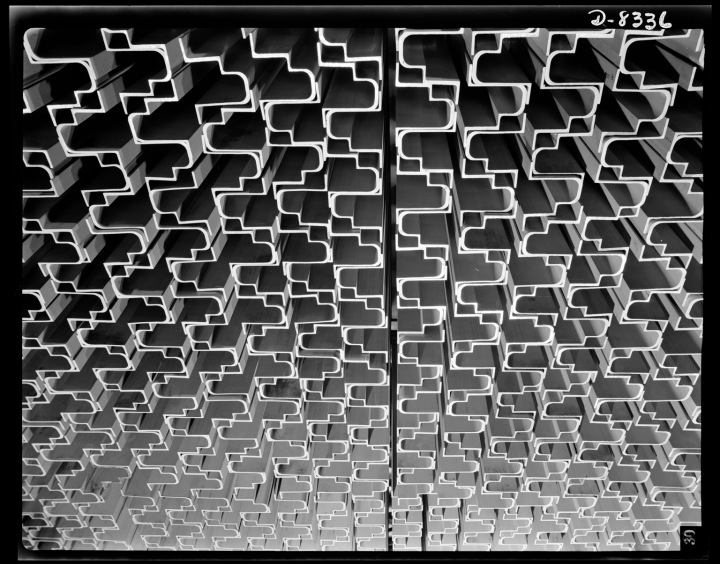

8. The raw material of victory – a vast stack of aluminium extrusions wait their turn in Boeing’s B-17 assembly process. The patterns and shadows clearly delighted Feininger’s eye. Northwestern aluminium production was put into overdrive by the Depression-era construction of the Bonneville Dam in Oregon – ideal for Boeing’s wartime needs.

Andreas Feininger, December 1942. (LoC P&P, LC-USE6-D-008336)

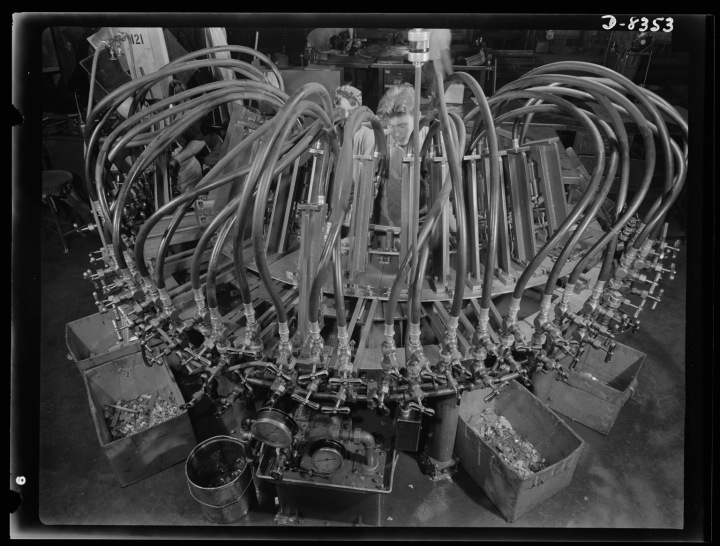

9. I don’t know what it is or what it does, but – wow! The original caption only mentions an “octopus punching machine” at Boeing, Seattle, and it appears to be used for making fuselage frames, or possibly wing ribs. If you know any better, please share the details.

Andreas Feininger, December 1942. (LoC P&P, LC-USE6-D-008353)

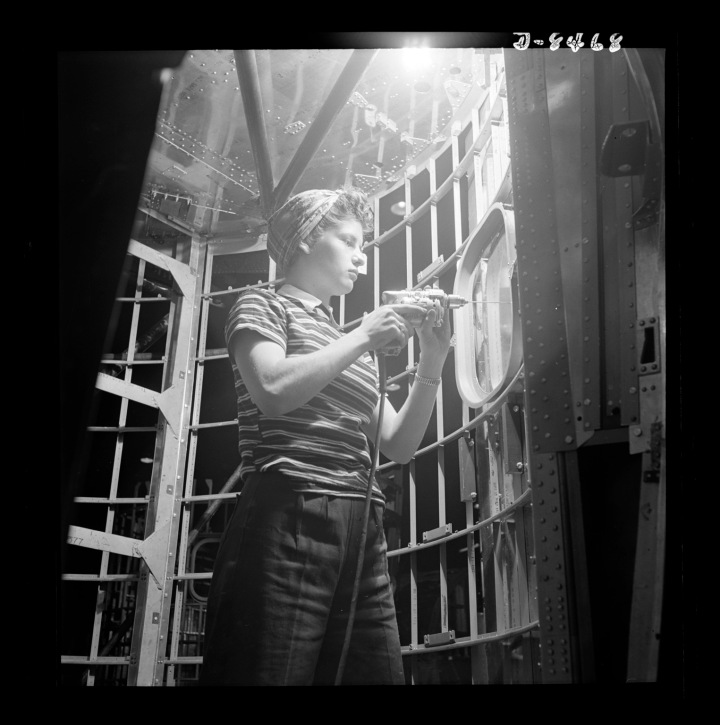

10. Feininger found over half of Boeing’s production workers were women – the kind of fact that was a big part of the OWI’s message. Feininger treated people as accessories to a more architectural subject in many of his images, however there’s better balance in this shot of a worker finishing the framing for a B-17’s forward fuselage. (The sections were constructed on end to simplify access and, more importantly, save floor space.)

Andreas Feininger, December 1942. (LoC P&P, LC-USE6-D-008468)

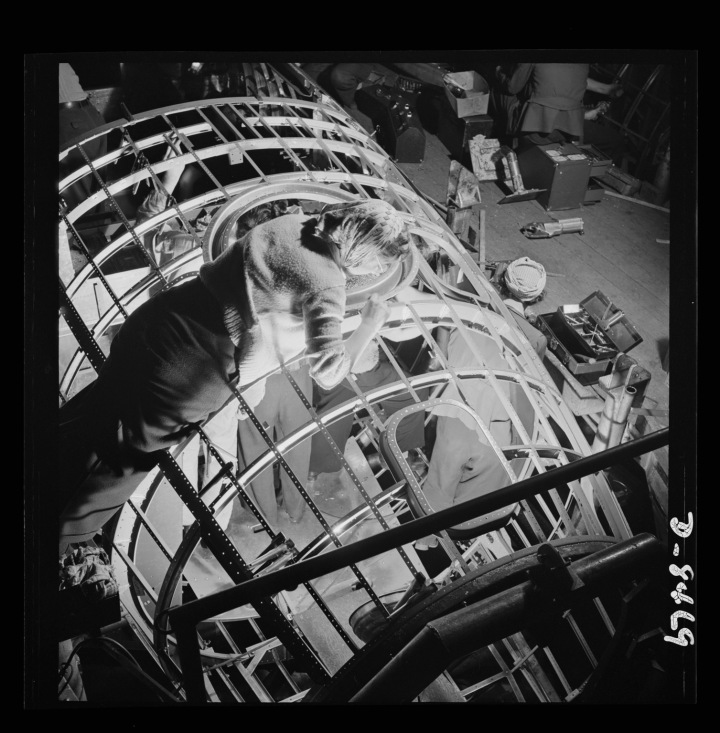

11. The OWI picture of dedication and skill, Boeing women work on the forward frame of a Seattle-built B-17F in December 1942. At this stage, Boeing was finishing it’s Block 50 aircraft (B-17F-50-BO) serialled 42-5350 to 42-5483, and starting into Block 55 serialled 42-29467 to 42-29531.

Andreas Feininger, December 1942. (LoC P&P, LC-USE6-D-008469)

12. Highlighting the size difference between aircraft part and the woman producing it, Feininger captures Boeing punch press operator Sharon Arnott as she finishes a B-17F wing rib. A stack of similar ribs waits at lower left. The exaggerated scale is classic Feininger and perfect OWI fare, showing women handling the daunting demands of the home front.

Andreas Feininger, December 1942. (LoC P&P, LC-USE6-D-008344)

13. A line of beautifully finished B-17F tail sections being worked on by Boeing staff. The farther units are still having their dorsal fillets skinned. Note the attachment structures for the empennage, then start thinking about how little space the tail gunner would have to crawl into!

Andreas Feininger, December 1942. (LoC P&P, LC-USE6- D-008444)

14. One of Feininger’s often-seen sequence of major B-17F components moving toward final assembly at Boeing. Despite first appearances, this school of forward sections is still a long way from completion, being little more than metal shells awaiting systems, components, fittings, tails, wings, engines, undercarriage and more. ’90% complete, 90% to go’, as they say.

Andreas Feininger, December 1942. (LoC P&P, LC-USW3-041070-E)

15. What it was all about – a brand new B-17F is run up on Boeing’s ramp, ahead of the manufacturer’s test flight. The lack of allowance for forward firing armament marks this as a fairly early B-17F that would probably have nose, cheek and even chin guns added at a completion centre or in in the field.

Andreas Feininger, December 1942. (LoC P&P, LC-USE6-D-008216)

Worth the wait? I can’t believe it’s been four weeks since the first part of this OWI gallery – and I apologise unreservedly. It certainly wasn’t meant to take this long AND there were meant to be other articles in between. Life, eh?

The various parts and assemblies really were works of art, every bit made by hand. The craftsmanship is especially remarkable when you consider how quickly they were designing and building these things.

The way hostilities evolved from Europe, American aircraft production was fortunate enough to be on a war footing by the time WW2 came to your shores in December 1941. SO speed was built into the production processes already. But the beauty thing… If an aircraft is a collection of parts, then it follows that something as beautiful as a B-17 or a P-38 should be a collection of beautiful parts. Still, I’m absolutely stunned by how gorgeous the motor parts were. Every rod and crank is like a piece of industrial jewellery. Who wouldn’t want a few for the den?

Thanks for compiling this collection of fantastic photos.

You’re very welcome. Don’t miss the previous post, ‘Works of Art’, which is a kind of Part 1 to this gallery.

Enjoyed that one as well. Thanks for the suggestion.

Reblogged this on Owl Works – The Scribblings of M.T. Bass.

Thanks!