Feature image © Thomas Kirn

G-AHEM (cn 1978) ‘Balmoral II’, sister to our

story’s aircraft G-AHEL ‘Bangor II’.

It’s not widely known that BOAC, forerunner of British Airways, continued to fly global services throughout World War 2 – and by 1945 no airline had more experience crossing the Atlantic.

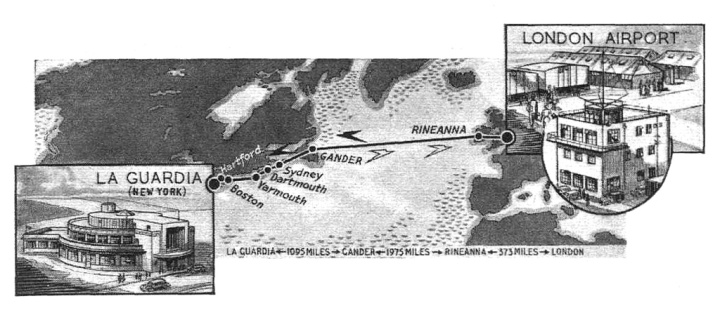

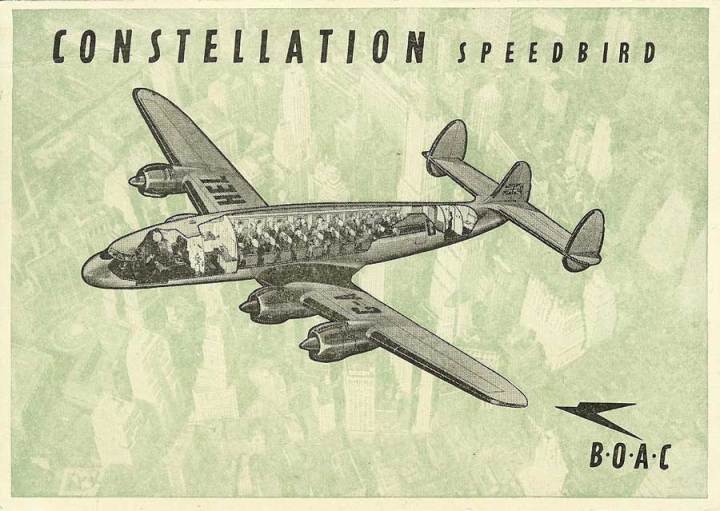

At war’s end, the airline was swift to acquire five Lockheed C-69 transports, completed as L-49 Constellations, for this route. So by 1946, even with a bomb-scarred Britain still under rationing and most of Europe in ruins, BOAC could offer an elegant Constellation service between London Heathrow (where the facilities were only canvas tents) and La Guardia in New York.

As this account of an initial proving flight shows, the experience mixed some familiar air travel frustrations with comforts that are long lost to us these days…

Cancelled, postponed, delayed

After rushing round London arranging dollar credit, along with trying to get a passport renewed and an American visa issued quickly by two hopelessly inadequate and under-staffed departments, all the usual pre-travel requirements were finally met.

Check-in and weighing took place at 7.30pm on Friday, June 21st. However, our departure was then cancelled, due to bad weather at Rineanna (Shannon) in Ireland. It would be quite within the Constellation’s capacity to overfly Rineanna, but this was not desirable on a proving flight, and unusually strong headwinds could always result in us running uncomfortably close to the fuel safety mark on East-to-West crossings.

The trip was postponed again on Saturday night because of a cabin supercharger problem affecting all Constellations, but after disconnecting the offending drive during Sunday all seemed ready for departure on Sunday night. Unfortunately, with this pressurising equipment out of use, the flight now had to be made below 10,000 feet. In fact, this made little difference to the comfort of the flight, although it was less satisfactory from the point of view of weather and aircraft operation.

And then, due to a minor hydraulic defect this time, our take-off from London was delayed by a further two hours.

Now there seemed to be an unwarranted delay following examination of our documents and passports, when passengers were ‘held’ in the tent by a zealous airport policeman until our scheduled time for embarkation. The BOAC officials were, however, most helpful and courteous. Relief from the stuffy tent seemed imminent when a Pan American Constellation started up nearby, but the flapping canvas and guy ropes managed to take the strain.

More time would be lost during the journey as ground staff at the intermediate stops weren’t completely familiar with the inconvenient freight-loading arrangements for Constellations, or the paper work involved.

All these delays reduce the greatest advantage of air travel – namely, speed from place to place – but also nullify the constant efforts of aircraft designers to find a few more knots of cruising speed.

by BOAC during WW2. British Airways photo

Into the night sky

Time to board arrived at last and after a short taxi and a long run up, G-AHEL was airborne and the lights of Heathrow were rapidly lost to view.

During preparation for take-off the noises of flap motors and other devices and the sudden dimming and brightening of lighting during engine starting is anything but reassuring to the average passenger; however, taxying and take-off were smooth and reassuring. The noise at full power is not excessive, while under cruising conditions a normal conversation can be carried on and the steady drone is quickly forgotten and becomes almost soothing.

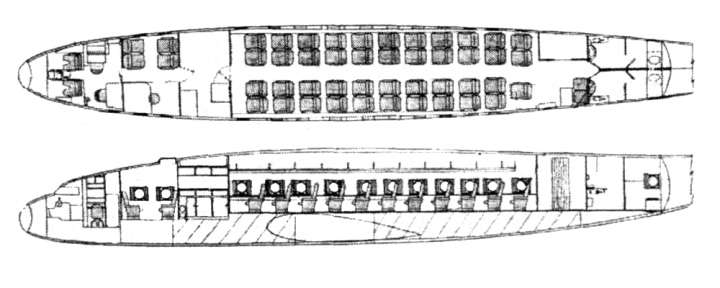

The cabin is quite comfortable and roomy. The best seat position is a combination of personal opinion and compromise. Forward near the engines there is more noise, while to the rear there is more vibration. The best compromise seems to be at about row seven.

The seats are arranged in forward-facing pairs with a central gangway and no transverse divisions. The angle of the seat back is adjustable over a wide range and the centre arm can be taken out. So, with the pillows and rugs provided, a comfortable sleep can be had in one seat or across two if the passenger finds a spare seat beside them. Individual lights are available at night, in addition to the bright corridor lights in the roof. There is a circular window beside each outboard seat.

West with the sun

From London to Rineanna we averaged 5,500ft and a true air-speed of about 270 knots. On arrival we descended through cloud into dirty weather, so some flap was lowered with a characteristic grinding noise, and at about 800 feet in a heavy shower the airfield came into view.

After a very light touch-down, and following a prolonged period of taxying, the door was opened and cool, damp air rushed in to revive the passengers for their late supper. After a few words of briefing in the aircraft everyone went into the pleasant airport hotel and enjoyed a meal of steak and strawberries with cream (second helpings allowed!).

Time for take-off was eventually announced (first in Irish then English) after some delay caused by the freight and its paper work. Dawn was already breaking as we headed West for Gander with a full fuel load. The weather was unsettled and two weak fronts lay ahead. Without pressure it would be necessary to fly through or under them and during our climb the leading edge de-icers could be seen writhing and pulsing in the dim light.

By 5.00am our position was 53.30ºN, 15.00ºW and our speed at 6,000 feet was 200 mph. The cabin was warm, but seemed rather dry to the throat.

Most of the passengers, including several young children, slept comfortably and awoke for a wash and breakfast to find the over-ocean journey nearly completed.

Wardrobes, washrooms and white bread

The Constellation has a wardrobe for coats and light overnight baggage at the rear of the passenger cabin, along with steward’s desk and, further aft, two separate toilets, comprising two compartments each. These seem barely adequate for a full load of 42, but passengers seem to be able to get a wash and electric razors help to relieve congestion round the men’s wash basin. Mirrors are in rather short supply.

Forward of the main cabin are the galley and the crew rest-room and stations. There is no sink in the galley and too little space for preparing and laying out the food trays. There is also insufficient drawer space for silver. The water tank for the rear basins is located in the roof of the galley and cupboards, with a dry ice refrigerator underneath.

The compartment is roomy but has no window, and much of the space is taken up with radio equipment and dinghies. An irritating high-whine (from the motor on the auto-pilot) can be heard in the cockpit and crew compartment, but otherwise it is quite quiet.

Both our airspeed and the outside temperature rose as we approached Gander in CAVU conditions. The rather lethargic atmosphere on board was soon dispelled by the thought of arriving in Newfoundland, and we passed the time chatting and spotting icebergs.

Captain W.L. Stewart let us down straight onto the wide East-West runway at Gander, and passengers were soon on a coach to the Airlines Mess a mile or two round the aerodrome. In the Mess, of standard RCAF pattern, the dazzling whiteness of the new bread caused more comment than any other part of the trip!

Pilot’s point of view

From the pilot’s point of view the Constellation has a number of good features, and the cockpit layout is characteristically systematic. The majority of the engine instruments and controls are grouped before the flight engineer but the essential dials, switches and levers are duplicated for the pilots. Ahead of each control column is a standard blind-flying panel with a S.C.S.51 indicator for blind approaches just outboard of these. In the middle are duplicate boost and rpm indicators and the Sperry auto-pilot panel. Centrally overhead are the radio compasses, VHF and HF controls, and electrical switches are grouped beside the captain’s seat on the port side.

Beside the pilot’s left shoulder, outside the window, is an ice pole to give an immediate visual indication of ice formation.

The central pedestal supports all the usual controls plus the auto-pilot engagement levers and trimmers. Particular features of this excellent gyro-pilot are the smooth engagement, ‘finger’ trimmers on the pedestal, and the duplicate trimming knobs on the Sperry panel. Army Air Corps specifications for the military transport called for a separate electric motor and self-contained power unit for the auto-pilot. This is continued on the interim Constellation and, placed in the nose, is the cause of an irritating whine in the cockpit which is otherwise very quiet.

Another notable feature is the optional powered elevator trimming device. In addition to the normal hand wheel, a switch brings a small electric motor into use, and by pressing with thumb or finger either of two small “firing buttons” on the control column, the pilot can adjust fore and aft trim on the approach without taking his hands off the control column and throttles.

The controls are heavy and it seems best to leave the rudder alone for straight flying. Ailerons feel typical for a large four-engined aircraft, and the elevators have a slow, rather delayed-action effect.

Should the power-boost fail, a leverage increase of 3 to 1 can be brought into use for the elevator controls and the aircraft can be flown safely but with reduced elevator movement and within certain c-of-g limits. When turning under these circumstances, differential use of engines is a great help.

Among the other devices fitted for emergencies is a vacuum change-over so any of the four engines can drive the blind-flying gyros. A final ultra-emergency supply from the cabin supercharger is also available should all other sources fail, and one panel can be isolated if the need arises.

Flying by the stars

Lockheed first designed the Constellation to meet TWA requirements before the War, and Pan American also placed an order. With the outbreak of hostilities those companies waived their rights and production was given over to the C-69 military version.

With peace, Lockheed were glad to take over the C-69 production line and announce almost immediate delivery of an interim L 49 airliner conversion. With speed of delivery in mind, airlines of Britain and several other countries placed orders.

Pure commercial Model 749 (‘Gold Seal’) Constellations are due in 1947. These will not differ outwardly from the L-49, but will feature refinements to cabin equipment, comfort and noise protection, as well as a later engine with two-speed superchargers and fuel injection giving 2,500 hp for take-off. There will be an all-up weight increase to 100,000 lb and a modified long-range wing with thermal de-icing.

An extra 1,000 gallons of fuel and 310 mph cruising speed will serve to make non-stop east to west crossings of the Atlantic possible.

New York and return

Having put our watches back 4-1/2 hours there was much more of the day left when we took off for New York. However this last leg proved the most tiring. The heat became rather uncomfortable and, at our height of about 4,500 feet, there were one or two rather bumpy periods.

The ground speed at Halifax was 236 mph, the height 4,200 feet and the air temperature 17ºC. After a cooler, steadier stretch over the sea between Yarmouth and Boston, the last leg into La Guardia was completed on ETA. The Constellation was soon parked outside the Marine terminal buildings, with passengers drinking orange juice to pass the 65-minute wait for attention from overworked immigration officials.

After a week in New York, Sunday lunchtime seemed to come round very quickly and it was time to emplane for the flight home. Bangor II, or G-AHEL, was the aircraft again, with Capt. L.V. Messenger in command.

It took very little time to check passports at La Guardia and, after a few minutes’ delay behind Pan American and AA aircraft ahead of us on the congested tarmac, we were airborne for Gander.

Flying north, the weather became appreciably colder, and at Gander it was necessary to put on jackets and waistcoats. Tea was taken with strawberries, ice cream and fruit cake. Everything was quickly and efficiently dealt with. Then, replenished with food and fuel, we commenced our west to East crossing at dusk – just a few minutes behind schedule.

We cruised at between 9,000 and 10,000 feet. At 0430 GMT, while at 10,000 feet, our ground speed was noted as 262 mph and the outside air temperature -7ºC. At 0700 we were flying at 9,500 feet with a ground speed of 282 mph and an OAT of -1ºC.

On waking up to bright sunshine and the steady roar of the engines, there was just time for a shave and wash before descending to Rineanna for breakfast.

No extra fuel was needed for the flight on to Heathrow and, with the Constellation flying light, the take-off and climb were particularly impressive. The initial climb to 2,000 feet took only 1 min 24 sec, and from take-off to touch-down took 1 hr 52min.

The return flight from New York seemed to bring home just what travel by air can mean: Lunch on Sunday in New York, take-off, read the paper, have tea, and Gander is seen below. Take off again, put your watch forward 5-1/2 hours and it’s time to sleep through to breakfast in Ireland. Final take-off follows then, with two further hours airborne plus one in a car, you can be in London just 24 hours after leaving New York.

__________________________________________________________________

Model 49 Constellation performance data

• Maximum at sea level 235 knots

• Maximum at 22,000 ft 260 knots

• Maximum at 25,000 ft 247 knots

Maximum speed for:

• Fuel jettison 189 knots

• Wheels down 152 knots

• Take-off flap 174 knots

• Landing flap 127 knots

Flaps

• Take-off 60%

• Approach 80%

• Landing 100%

Asymmetric flight

• Minimum control speed on three engines at take-off power 81 knots

• Minimum control speed with two engines feathered on one side 110 knots

• Critical engine-failure speed on the ground during take-off 92 knots

Critical weights

• Maximum take-off weight 90,000 lb,

• Maximum landing weight 77,800 lb up to 6,000 ft altitude with full runway

Stalling

The stall at about 80,000 lb weight with full movement of aileron is gentle and straight, with a fairly pronounced shudder at 77 knots indicated. The nose position at the stall is very high and becomes more so with the use of a little engine power.

__________________________________________________________________

This article is compiled from a two part feature by Maurice A Smith, first published in Flight on July 11th and 18th, 1946. You can read and download the originals here.

Awesome Connie article!!!!! Thanks for sharing😃😃😃

I’m glad you enjoyed it. I hope you also found ‘Triple Tail’ – the article on the history of this L-049. (There’s a link at the end of the page.) I’ve just been given access to a collection of private photos from BOAC’s Constellation days as well, so airscape will have even more on these beautiful prop-liners soon.

1958 I emigrated to the US on an Irish Airlines L1049 (operated by Seaboard Western) a very similar flight to the one in this article, except that we terminated at NY Idlewild. I had flown in L1049s a lot as I had worked for Flying Tiger Line all over Europe for 2 years but this was my first Trans Atlantic trip. I returned to working at FTL and worked all over the US and the Far East for several years. Thanks for a great article. John Townes.

Thanks John. Ageing Connies did amazing service all over the world for a lot of years. As an FTL alumni, I guess you’d know that better than most.

I wonder if you ever realised how much we’d miss them!?

The Flying Tiger Line is a shining star in aviation history and it’s always surprising how many people worked their spanners and air routes. If you have any memories or photos you’d like to share, I’d be delighted to provide the medium.

Sadly I don’t have pics, but I sure have memories. I started a book about all the different airlines I worked for all over the World. As the Tigers work was mainly seasonal, I was laid off many times but always went back because it was a such an amazing company to work for. I will get back to you.

BTW do you know Bill Charney? He has a Beech Staggerwing that was rebuilt by the Croydon Aircraft Co in NZ. After completion he spent 2 years touring NZ and then flew it to Europe. I joined him in the UK at the Goodwood Revival for 2 visits where he won the Concours the 1st year. He has been touring Europe every summer for the past 6 years and the plane is in storage for the winter near Lake Garda in Italy. He will be taking it to Normandy for the 75th anniversary along with some 25 Dakotas. His plane was with the Royal Navy in the UK during WWII. He and I went to see ‘They Shall Not Grow Old’ last night here in Reno NV and I was very moved by this wonderful film. Bill had a hard time with the Pommie accents, but of course that was not a problem for me.

We have a couple of active Staggerings down here, but I never got to meet Bill when he was passing through with N16S. Great to hear that he’s hale and hearty of course. Feel free to pass on a very incomprehensible “G’Day” to him, from the colonies. 🙂

Roger that,

will do. Cheers mate.