There is no shortage of online video and imagery covering the time the US Navy landed a C130 Hercules on an aircraft carrier.

And that was categorically a landing, not an arrested ‘trap’: The trial off Florida saw KC-130F (BuNo 149798) captained by Lieutenant James H. Flatley III come aboard USS Forrestal (CVA-59) on 30 October 1963, with the legend ‘Look ma, no hook’ emblazoned on its nose.

In all, the Herc crew and Jerry Daugherty, landing signal officer (LSO) for the flights, achieved 29 touch and go landings, 21 unarrested full stop landings and 21 unassisted takeoffs, at weights of up to 121,000lbs (54,884kg).

The aircraft was eventually retired to the National Naval Aviation Museum in Pensacola, Florida in May 2003 and remains part of the collection there.

However, beyond the ‘gee-whiz’ factor of bringing a 60-ton, 132-foot span (40.2m) cargo plane safely to rest on a heaving carrier deck, very few people have ever asked my (and every other three-year-old’s) favourite question – “But why?”

The answer to that is even more extraordinary. Because the Hercules landings were really just a logistics test for operating Lockheed’s legendary U-2 spy plane ‘off the boat’…

And yes, they did that too!

(For more, watch this interview with Rear Admiral Flatley – paying particular attention at 16:25.)

Finally and fully blown

In the early 1960s, the U-2 was going through something of a public relations crisis. Never a good thing for a top secret platform.

After Francis Gary Powers was shot down deep inside Russia on 1 May 1960, the CIA’s ‘weather research’ cover story for the U-2 was finally and fully blown. As a result, friendly nations with suitable airfields near Soviet borders (Turkey, Japan, Norway) were not overly enthusiastic about being seen to host the long black planes. The US might appreciate it, but their Soviet neighbours were bound to take a dim view.

As the program was slowly rebuilt, intelligence gathering over Cuba was the immediate priority. But the CIA was desperate to have its flexible, long range photo-recon capacity restored. For one thing, the U-2’s cameras offered ten times better resolution than the early Corona satellites – the next best alternative.

With an array of suitable land bases seemingly off-limits, the US Navy’s carrier fleet seemed like an ideal source of runways that could be positioned wherever they were needed with minimal diplomatic groundwork.

As old as the U-2 itself

As it happens, the idea of operating the U-2 from carriers was almost as old as the U-2 itself.

Kelly Johnson and his team at the Lockheed Skunk Works had proposed a carrier capability in their initial CL-282 proposals. President Eisenhower had supported the idea and it was recommended to CIA chief Allen W Dulles by the Chief of Naval Operations, Admiral Arleigh Burke. But the perennial turf war between the US Navy and Air Force, which was administering the project for the CIA, saw the idea of seaborne operations swiftly nixed.

“The carrier capability…would add little to the coverage of the Soviet Bloc obtainable b the U-2 from the land bases to which it now has access,” the Navy was told.

Taking the U-2 to sea

The Navy continued to press its case through the late 1950s but, despite U-2 operations being heavily curtailed by the events of May 1960, it wasn’t until 1963 that anyone breathed life back into the idea.

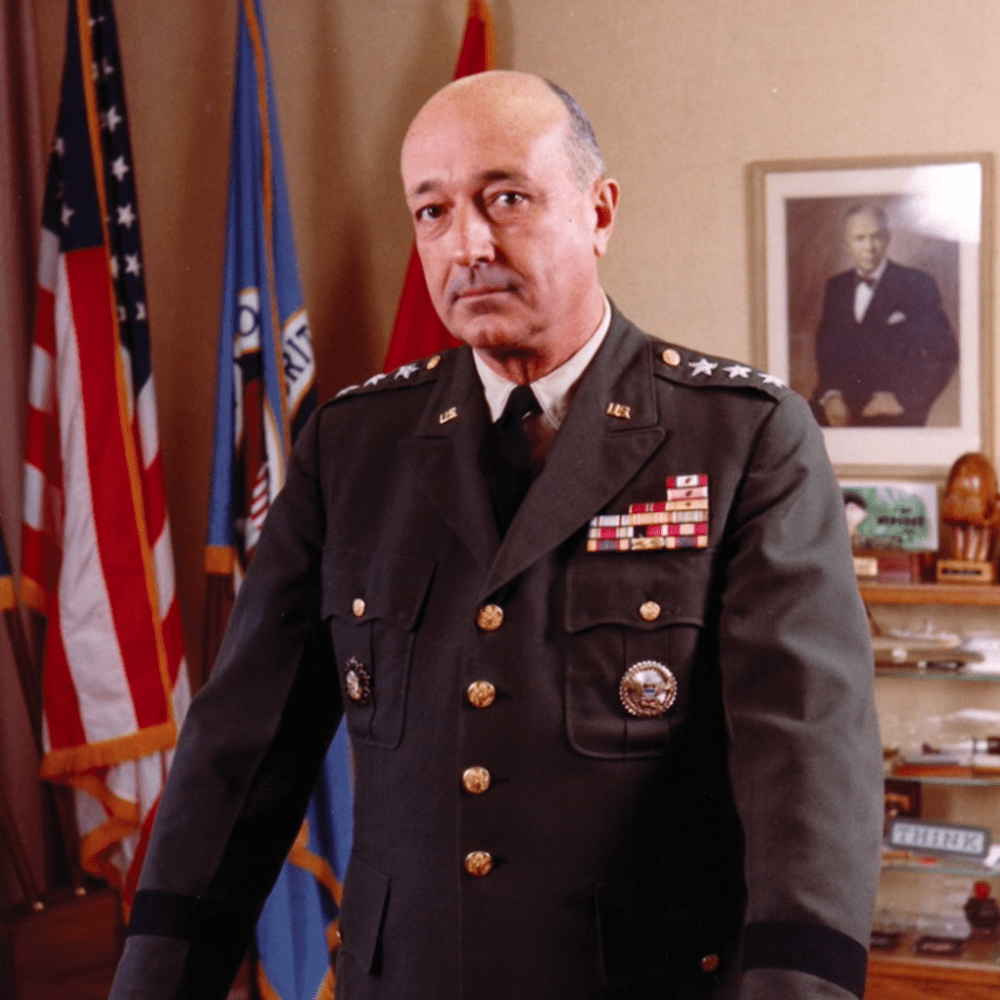

That ‘anyone’ was specifically Deputy Director of the CIA Lt. General Marshall Carter, who was a personal fan taking the U-2 to sea. He felt a carrier conversion could be completed fairly economically, so he went directly to Lockheed and asked Kelly Johnson to evaluate and cost the project.

This work was complemented by a CIA Office of Special Activities feasibility study where several carrier captains and senior officers were interviewed about the possibility and potential problems of operating the U-2 from Navy carriers.

Their conclusion was that it would be feasible. The greatest problem was thought to be the U-2’s nose-down approach attitude, which would make rotating to engage an arrester hook anywhere from difficult to dangerous: If the aircraft was flying too fast it could easily balloon and miss all the wires; if it was flying too slow it would stall and slam onto the deck.

It was thought a flat, power-on approach with a descent angle of 1-1/2 to 2 degrees could mitigate the problem.

The only other significant issue was that the aircraft’s 80 feet (24.4m) wing span was significantly larger than the 63 by 52 feet (19.2 x 15.8m) main elevators on the latest Forrestal class carriers (CVA-59 to CVA-62).

Lockheed overcame this by developing a special cart called ‘Lowboy’, which could be used to move U-2s on and off the elevator sideways, with a sizeable portion of one wing projecting overboard.

Lockheed’s engineers also designed a special lifting sling that supported the wingtips while the fuselage was lifted by a dockside crane, so U-2s could be embarked and disembarked manually, if needed.

With those hurdles overcome, operation WHALE TALE – a U-2 carrier trial – was given the green light.

In the small hours of Saturday morning

While design work began in the Skunk Works, the CIA and US Navy sketched out a ‘clear and plausible’ cover story for the operation. Taking a page from the 1950s, when NACA covered for early U-2 test flights, they would claim the operations were a perfectly innocuous Office of Naval Research project and nothing to do with the CIA or intelligence gathering at all.

Late on Friday the 2nd of August 1963 Article #352 (56-6685), a standard U-2C marked as ‘N315X’, was flown to North Island Navy Base at San Diego then, in the small hours of Saturday morning, quietly hoisted aboard USS Kitty Hawk (CVA-63) and stowed below decks.

All the personnel required to be involved in the midnight operation were told to keep the sensitive “Office of Naval Research operation” to themselves. To add credence to that cover, the U-2 had ‘ONR’ painted on its tail and everyone associated with the project said they worked for the ONR or Lockheed.

Into the wind

Kitty Hawk sailed the following day, taking up station some 50 miles off the California coast for the top secret trial. An extensive lookout was posted for other ships or aircraft and the U-2 was brought up to the flight deck. While it was readied, the ship’s commander Captain Horace H. Epes announced to the crew that they were about to conduct a classified exercise for the ONR, aimed at enabling high-altitude infra-red detection of submarines at sea – the CIA’s agreed cover story. He then order the ship brought into the wind.

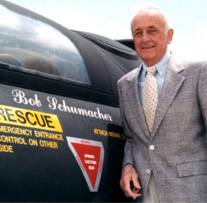

With 30 knots of wind across the flight deck, the long-winged U-2 had to be virtually held down by the crew while Lockheed test pilot Robert Schumacher prepared to launch.

Schumacher was an ideal choice for the role. He had earned his wings as a Navy pilot in World War 2, flying Douglas SBD Dauntless dive bombers off the Essex class USS Bennington (CV-20) and earning a Distinguished Flying Cross for his part in attacking the formidable Yamato task force on 7 April 1945. He joined Lockheed as a test pilot in 1952 and had been flying U-2s since 1956.

As a catapult launch had the potential to tear the U-2 apart, it was planned to launch the aircraft under its own power. And that’s what Schumacher did.

To the astonishment of Kitty Hawk’s deck crew, the big black bird was airborne within about a third of the available flight deck length and, climbing steeply, was at nearly 1,000 feet by the time it passed the bow.

Schumacher executed a program of flight manoeuvres before returning to the ship for a series of low angle approaches to assess the controllability of the aircraft in the disturbed air behind the ship. He found the turbulent wash needed to be compensated for with large throttle adjustments, but it could be managed.

Then, on his final pass, he attempted a landing.

All but impossible

As the preflight deck handling problems had indicated, bringing the unmodified U-2 to a controlled stop in the high winds of the flight deck was all but impossible. Despite Schumacher’s considerable skill, the aircraft bounced, came back down and hit a wingtip, then barely made it back into the air before running out of deck when full power was reapplied.

Lesson learned, Schumacher flew directly back to the Lockheed plant at Burbank to have the aircraft assessed (and repaired).

However, WHALE TALE had done its job.

The CIA and Navy had established that U-2s could be operated successfully from modern supercarriers and Lockheed had fully validated the engineering requirements needed to provide a carrier capable version of their spy plane.

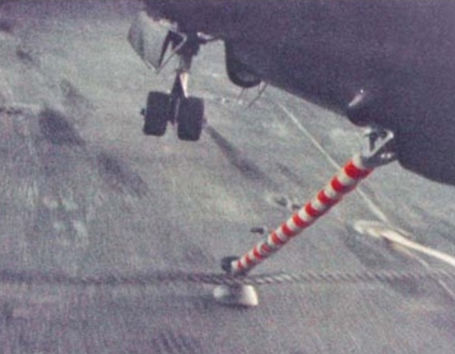

The U-2G would need beefed up landing gear and an arrester hook. This hook was covered by a drag-reducing plastic cover which would be dumped on the downwind pattern leg before landing. The pressure bulkheads behind the gear wells and the aft longerons were also strengthened to accommodate the forces of arrested landings and a mechanical fuel dump system was added in case the aircraft needed to return to the boat while still above minimum landing weight.

Finally, mechanical lift dumpers were installed on the trailing edge of each wing, with an activation switch on the throttle quadrant. The idea was that these would be activated precisely on the point of touchdown, so the pilot could ‘stick’ the aircraft to the deck with predictable accuracy.

To keep costs down, conversions would be made from U2-A airframes that had been slated for upgrade to C standard already.

Incidentally, the lightest 1 inch (25.4mm) diameter weight arrester cables were also specified for U-2 operations, instead of more normal 1-1/4 or 1-3/8 inch (32 or 35mm) pendants, in order to reduce the shock on the lightweight rear wheel is it rolled over the wires.

Carrier qual

The next phase of the project was a carrier training program for a select cadre of Agency U-2 pilots and was dubbed WHALE TALE TWO. These pilots were given initial type training in North American T2A ‘Buckeye’ trainers and taught the fundamentals of carrier approaches and landings at Naval Air Station Monterey, California. They then deployed to Florida for simulated carrier landings in the T2A at NAS Pensacola and carrier qualification aboard USS Lexington (CV-16) in the Gulf of Mexico.

The first group of four pilots began their training at Monterey on 17 November 1963 and were all carrier qualified by the end of the year. A second group of six went to Monterey on 5 January 1964 and had completed carrier qualification by 15 February. In that alone, their skill speaks for itself.

Phase 3 of Whale Tale II involved rehearsing carrier flight profiles and simulated landings in the new U-2G. Accordingly, the first of two U-2G conversions, Article #348 (56-6695, marked as ‘N801X’), was delivered to the Agency at Edwards Air Force Base on 29 February 1964, where the pilots would use it to hone the techniques they had learned in the Buckeye. Make a note of that date.

WHALE TALE THREE

Having established the confidence and capability of its pilots at Edwards, the CIA immediately initiated WHALE TALE THREE – another three phase operation that would demonstrate the actual carrier operation and integration for the U-2G and its pilot contingent.

The first phase involved Lockheed demonstrating the U-2G’s suitability for shipboard operations.

For this, the CIA Office of Special Activities had already cooperated with the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations and the Commander Naval Air Pacific, Vice Admiral Paul D. Stroup to arrange a window for operations for USS Ranger (CV-61).

Again, a contingent of Lockheed and CIA personnel with their equipment were spirited aboard their carrier at North Island in the dead of night on 28 February 1964. Remember, Phase 2 of Whale Tale TWO had only been completed on the 15th, and those pilots received their first U-2G for Phase 3 practice approaches at Edwards AFB the day after the company’s technicians went to bed on the carrier!

Fast and a little high

By the time #348 was being welcomed by the pilots at Edwards, Ranger was already proceeding to her test area off San Diego, where Bob Schumacher duly arrived overhead in the second U-2G conversion, Article #362 (56-6695, likely marked as ‘N808X’), and performed a series of touch and go landings on the boat.

As these all went well, apart from expected turbulence aft of the boat, the call was given to attempt an arrested landing.

Schumacher flew a largely stable approach but compensating for the carrier’s wash brought him over the wire fast and a little high. The U-2 bounced on touchdown and the tailhook caught a wire while the aircraft was back in the air. Unsurprisingly, this decelerated the airplane sharply, causing the nose to drop and impact the deck.

The damage turned out to be relatively minor, however, and the U-2 was taken to the hangar deck and repaired. Schumacher took off later the same afternoon and flew #362 back to Burbank where Lockheed engineers assessed the instrumentation read-outs and fitted a sprung steel ‘pogo’ under the nose to prevent further mishaps.

Delayed for a week

The exercise was repeated on 2 March 1964. This time, Schumacher flew Article #348 out to Ranger from Edwards AFB and completed four arrested landings without incident.

He then took the Dragon Lady back to Edwards and handed it over CIA pilot Robert Ericson, who flew to the boat and conducted his own series of touch and gos. However a Norwegian trawler blundered into the operating area and Ericson ran short of fuel while waiting for Ranger to manoeuvre clear.

He was forced to divert to North Island to without having attempted an arrested landing, and shut down the aircraft with just 5 gallons (18.9 litres) of fuel remaining.

Jim Barnes, another CIA pilot, picked up #348 the following morning and flew it to a rendezvous with Ranger. Unfortunately Barnes allowed the right wing to drop on his first touch and go, and the right-hand wing skid caught a wire and was torn off. He added power and flew clear, then headed back to Edwards and landed on the dry lakebed there.

With both U-2Gs now being worked on, WHALE TALE THREE was delayed for a week. However, the Agency pilots continued to practice their approach and landing technique at Edwards using U-2s and the experience they had gained on Ranger.

Over 9 – 10 March 1964, Ericson, Barnes, Eugene ‘Buster’ Edens and James Bedford Jr. all completed a series of wave-offs and arrested landings aboard Ranger and qualified to operate the U-2 from Navy carriers.

Like Shumacher earlier, Bedford hit the deck of the carrier with the nose of his U-2 on his third trap. The aircraft was taken to the hangar deck for repairs while the other U-2 was refuelled on board and flown off to Burbank by Schumacher.

Despite this minor incident, WHALE TALE was considered complete, and the CIA had an operationally ready carrier detachment.

Ironically, the new-found capability was hardly ever used.

Above: U-2G carrier qualifications aboard USS Ranger, 9 – 10 March 1964.

FISH HAWK: Maximum discretion

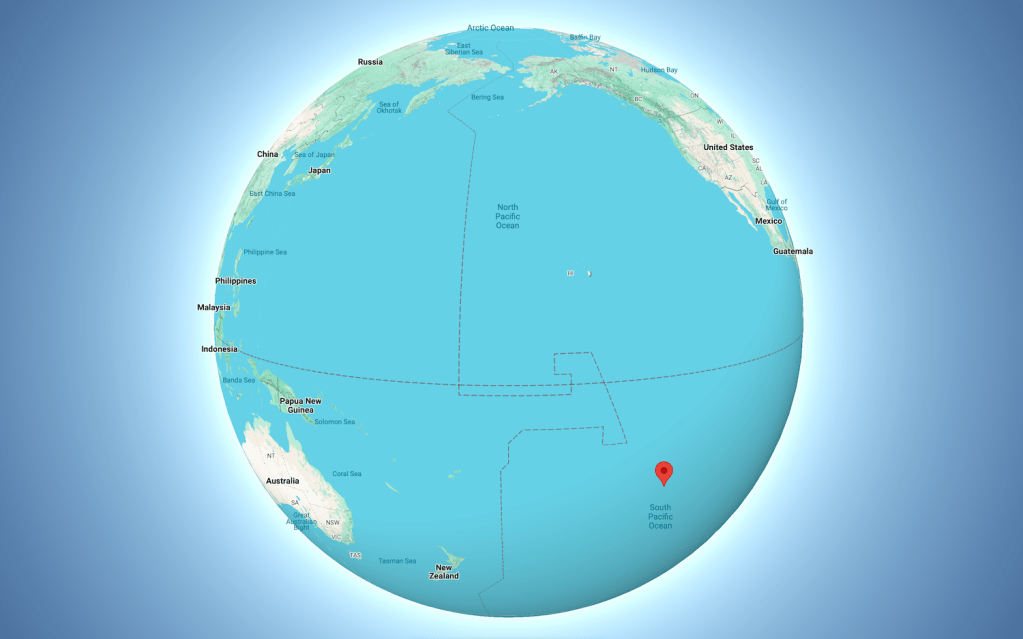

The only confirmed U-2 carrier deployment was Operation FISH HAWK, which was launched from the familiar deck of USS Ranger in May 1964 to surveil French nuclear tests in French Polynesia.

France had established a nuclear weapons test facility on remote Mururoa Atoll in 1962, but their announcement of an atmospheric fusion (hydrogen) program in 1964 triggered a need for detailed information in the US.

Large amounts of information about FISH HAWK remain classified. Spying on a nominal ally – even the fiercely independent French – was always going to be a delicate affair.

For maximum discretion, a U-2G was flown west from California and landed aboard Ranger off of Hawaii. The ship then proceeded south with a reduced compliment (which included a specialist CIA photo interpreter) and under heavily restricted radio and air activity. She took up station 800 miles (1,481 km) from French territory to await eight hours of ideal weather and sea conditions for the launch, flight over Mururoa and subsequent recovery of the U-2.

Conditions were deemed suitable on 19 May but the attempt was foiled by cloud cover over the target. A second flight was authorised and flown successfully on 23 May. Once the U-2 was recovered, one of Ranger’s carrier onboard delivery (COD) aircraft flew the 6,000 feet of mission film back to Hawaii. It was taken from there to Rochester, NY for development by Kodak, while Ranger and her CIA contingent withdrew.

If France ever detected the high-flying spy over their distant atoll, or wondered how it was operating some 3,000 miles (5,556km) from the nearest suitable US air base, they kept their mouths fermé.

Carrier-ready until 1970

Beyond this mission, the CIA found carrier deployments cumbersome to organise, while more flexible access to foreign land bases became simpler as the memories of Francis Powers’ shoot-down faded.

However, the agency maintained its carrier-ready Detachment G until at least 1970.

Along with Articles #348 and #362, Articles #349 (56-6682) and #381 (56-6714) were also converted to U-2G carrier configuration in 1964. When Article #362 was lost on a mission over Fujian, China on 7 July 1964, Article #349 was upgraded to the carrier configuration. Article #382 (56-6715, N804X) was also converted to a U-2G in 1965, and lost during a training flight in April that year, killing carrier-qualified pilot Buster Edens.

When the much revised and enlarged U-2Rs entered service in 1968, they were delivered with carrier equipment baked in, including 70 inch (1.78m) folding wingtips. Their capability was established by senior Lockheed test pilot Bill Park along with two American and two British U-2 pilots as Operation BLUE GULL on 21, 22 and 23 November 1969 using USS America (CV-66) as she steamed off the coast of Virginia.

Carrier qualification for each pilot, and the U-2R itself, comprised two wave-offs, four touch and go landings and four arrested landings.

The only hitch on this exercise was someone neglecting to remove the safety pin from Park’s arrester hook before his first sortie, requiring a quick return to base. After that, all five pilots qualified smoothly.

However, this appears to be the final carrier exercise by U-2s and continued carrier readiness is not acknowledged after this date.

Less than good

In a June 1965 memo, the CIA asked Lockheed to explore automatic deployment of the lift dumper at touchdown for the U-2G, pointing out that the pilots had their hands dangerously full as they rotated the aircraft in pitch, maintained wings-level, retarded the throttle and activated the spoilers in the split-second act of catching a wire. Alternatively, Lockheed was asked to consider deployment of the lift spoilers in flight and using extra power to maintain the approach profile.

Kelly Johnson himself had already acknowledged the dangers of U-2 carrier operations. In October 1964, he’d written a memo to the CIA defending the payment of danger bonuses to Bob Schumacher (and presumably billed to the Agency) for his earlier carrier trials. Johnson explained that the aircraft’s light wing loading and configuration changes had led to several close calls, hard landings and the arrested bounce on 29 February 1964. In addition, Schumacher had needed to work through unpredicted buffeting, tail vibrations and stall behaviour caused by the addition of spoilers.

Johnson stated that the danger bonus negotiated with Schumacher at the outset of the program was probably less than was eventually deserved!

On balance, the CIA agreed to the payment, adding in their approval memo: “It is also worth noting that there was no tested underwater escape system in the U-2G at the time of the tests so had the aircraft impacted in the water on landing escape prospects could be considered less than good.”

The ultimate test of skill

This all leaves us with less of a legacy of U-2 carrier operations, and more of testimonial to the remarkable skills of the pilots who flew the Dragon Ladies in all skies, all weathers and, incredibly, on and off ships.

I have no direct or personal experience, but I am pretty sure that becoming carrier qualified in an unfamiliar aircraft type in just four weeks is pretty special.

And I am positive that landing the USAF’s most-difficult-to-land aircraft with the bankable precision required by carrier operations is the ultimate test of skill.

Hats off to the men who flew the U-2!

I think your last paragraph said it all: a hard to land aircraft which wasn’t designed for shipboard operation, combined with the challenges of flying off a carrier — that would have been a tall order for the best of pilots.

Speaking of which, I had an Air Force pilot as a student one time. I think he flew the F-16. Anyway, he came to me to get a tailwheel endorsement because it was suggested that this might help him when he transitioned into his new ride: the U-2. He was the only tailwheel student I’ve ever endorsed after a single flight. He did everything right, the first time, and every time. Every taxi exercise was soon on. I figured we’d get through some 3 point ladings and I’d demo a wheel landing on the first hop. Nope. He flew perfectly. So I started bouncing his landings or hitting a rudder in the flare to cause the nose to diverge from the flight path. He corrected it properly every time. I demoed a single wheel landing and he did them perfectly from then on. Crosswinds? No problem. I’d have him come in super high and slip it all the way down. No sweat.

By the end, I was trying to think of some reason NOT to endorse him, and couldn’t come up with one. I was almost looking around to see if there was a hidden camera someplace. Did someone put you up to this? Are you SURE you’ve never flown a tailwheel before?

–Ron

Great story, thanks Ron. I bet they didn’t prepare you for that at CFI School! I’m pretty sure I read in ‘The Right Stuff’ that a couple of the Mercury astronauts pulled exactly that prank on an attractive flying instructor in New Mexico or somewhere – taking ab initio lessons from her for a laugh.

Seriously though, I suspect your pilot was an honest combination of natural talent and discipline. I know the Air Force only selects the best for programs like the U-2, but I bet your guy had studied every single aspect of tailwheel flying long before he went near your cockpit.

As I like to tell my soccer-mad son: Natural talent will only get you so far – and that’s to your next training session. There’s no substitute for doing the work. (He doesn’t listen, but I still like to tell him!)

I tell my son the same thing! … he doesn’t listen either.

#kidsthesedays

M’eh. Probably doesn’t matter. Based on my experience, they’ll end up saying it to their kids anyway – and the torch will have been passed. 🙂 #kidsforever